Insurers Said They Could Return Home. Our Tests Found Neurotoxins in Their Bodies.

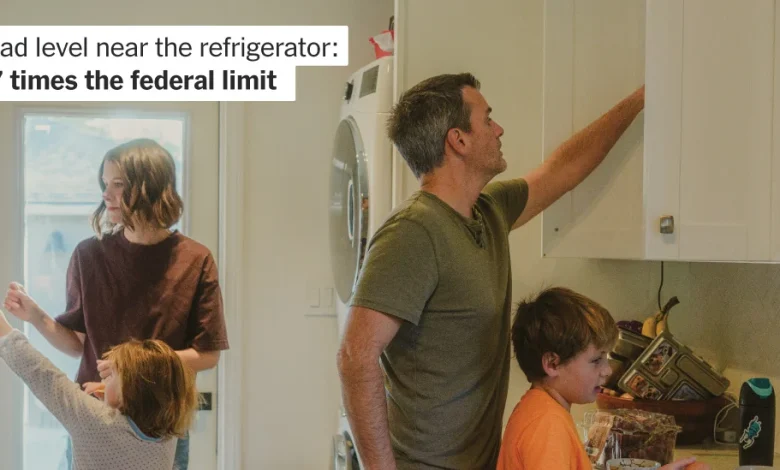

Near the refrigerator, the lead level was

27 times the federal limit. And that wasn’t all.

Jeff Van Ness is constantly cleaning.

Every day, he vacuums, mops and wipes every surface in his house, which stands on one of the blocks in Altadena, Calif., that survived the flames of the Los Angeles wildfires, but not the smoke.

He works in deliberate lines across the kitchen tile, then along the baseboards, then into the corners where the smoke pooled nearly a year ago — following a map only he can see.

It’s the only way to quiet his thoughts: Is it safe for his children, 6-year-old Sylvia and 9-year-old Milo, to walk barefoot on the kitchen tiles? Should he wash the toys they drop on the floor with bleach, or with soap and water? The darkest thoughts are about his wife, Cathlene Pineda, 41, a jazz pianist who is on medication for cancer. If the toxins were in the house, he wonders, could they bring the cancer back?

The family reluctantly returned home in August, eight months after the Los Angeles fires and two months after a consultant they hired found lead — a dangerous neurotoxin — inside the house. After their insurer, Farmers Insurance, dismissed those findings and cut off payments for their hotel, the Van Nesses had little choice but to return and do the only thing they could: clean.

“We don’t have the means to pay our mortgage and live somewhere else,” said Mr. Van Ness, 44, a waiter at a five-star hotel. “It’s a feeling of helplessness that is indescribable.”

Lead level in the dining area:

7 times the federal limit

For nearly every house reduced to ash by the fires that blackened the Los Angeles sky last January, another was left standing but steeped in smoke, according to an analysis by The New York Times.

These homes sit at an uncomfortable juncture: intact but potentially contaminated.

Like most insurance policies in California, the Van Nesses’ contract with Farmers — the second largest home insurer in the state — covers smoke damage, but it doesn’t spell out how the damage should be repaired. That’s because there are no state or federal standards for how an insurer should remediate a smoke-damaged home after a fire. In May, the California Department of Insurance created a task force to establish such standards, but until its recommendations are announced, families like the Van Nesses are caught in a regulatory no man’s land.

A growing body of research shows that smoke from urban wildfires, like the ones that engulfed Altadena and Pacific Palisades, is more dangerous than smoke produced when vegetation alone burns. Ordinary objects become poisons when extreme heat turns them into gases. The button you push to start your car often contains beryllium — harmless when sealed in metal but highly toxic once airborne. A car’s tires can melt into a cloud of benzene, as can the foam in a sofa. The handle of a kitchen faucet can give off chromium.

Microscopic particles carried by the smoke slip into a home’s insulation, lodge in the seams of hardwood floors and pass through the mesh in kitchen tiles, contaminating the space with carcinogens and other toxins. Industrial hygienists and toxicologists insist that removing the contamination requires tearing out nearly every surface the smoke touched — not just the insulation, but the hardwood floors, tiles, plaster and stucco.

By contrast, the insurance industry is relying on what experts interviewed by The Times describe as outdated or incomplete research, endorsing cleanups based only on what can be seen and smelled. If insurers test at all, it is for a small subset of contaminants.

According to more than two dozen scientists, insurance adjusters and consumer advocates interviewed for this article, as well as a review of thousands of pages of internal insurer documents, this approach is supported by a small roster of industry consultants who cite research papers that have not been peer-reviewed, or were funded by the insurance industry.

“We call it the tobacco playbook because it was done for so long and so successfully by an industry that was making a deadly product,” said David Michaels, who served as the assistant secretary of labor directing the Occupational Safety and Health Administration from 2009 to 2017, and who has written two books detailing this strategy. “This is absolutely the latest iteration of ‘science for hire.’”

The Exposure

To understand what happened to the Van Ness home and whether it was safe to return over the summer, The Times asked the family for permission to have a certified professional test for lead and other heavy metals in each room, and to submit strands of hair so scientists could measure family members’ exposure to these metals over time.

By then, the house had already been extensively cleaned.

In February, a contractor hired by the family carried out the remediation that Farmers Insurance had recommended: The attic insulation was ripped out, floors were vacuumed and mopped, countertops and other surfaces were wiped, carpets and drapes were laundered and air scrubbers were left roaring in every room.

By March, dangerous chemicals were being found inside neighboring homes. But Farmers’ tests concluded that the Van Ness house was safe inside, finding hazardous levels of lead only outdoors.

Those findings were contradicted by an independent test the family paid for in June, which showed lead above the federal threshold in the living room and in the attic — results that Farmers dismissed. That was when Mr. Van Ness repainted the walls and began his obsessive cleaning.

The readings commissioned by The Times were taken in September — a month after the family had moved back in — and allowed reporters to see whether the home remained contaminated, and whether the Van Nesses had been exposed to harmful substances.

Six of the 11 samples collected in the house showed unsafe levels of contaminants, including extremely high levels of lead which is known to metabolize quickly, leaving the blood and entering bones and tissue. No metals were found in the other five samples taken from the bedrooms, the living room, the piano and a wooden toy.

Sept. 26: Where testing by The Times found lead and other metals after the house was remediated.

The readings showed 27 times the federal hazard limit of lead on the floor next to the refrigerator, and more than seven times the limit where the kitchen tile meets the dining room floor.

A sample taken from the HVAC in the attic found lead levels close to 8,000 micrograms per square foot. Although the Environmental Protection Agency does not set lead-dust standards for attic surfaces, a rule change passed during the Biden administration holds that any reportable level of lead dust inside a home is considered a hazard. The concentrations found in the attic were “sky high,” said Joe L. Nieusma, a toxicologist who was one of 10 experts who reviewed the results.

“There are multiple carcinogens in the house and extremely high levels of lead,” Dr. Nieusma said. “It’s not safe for humans — or animals — to live in that residence.”

To determine whether the toxins inside the Van Ness home had made their way into their bodies, The Times commissioned Manish Arora, vice chairman of environmental medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and the creator of a technology that uses strands of hair to measure a person’s exposure to chemicals in the environment.

One centimeter of hair represents approximately one month in a person’s life.

“Every other test is like a snapshot,” Dr. Arora told the family, explaining why their blood tests were negative. “Hair has the ability to map back in time. It’s like a molecular movie.”

After reviewing the family’s hair samples, Dr. Arora concluded that the Van Nesses had been exposed to dangerous levels of toxins.

Each family member’s strand of hair showed “measurable spikes in heavy metals after they returned to the home in August, indicating a period of elevated exposure,” he said. The results revealed that Milo had elevated levels of all 11 chemicals that Dr. Arora’s lab tested for, including lead, a potent neurotoxin with no safe level of exposure in children. Sylvia’s hair showed elevated levels of nine chemicals compared with the exposure levels of 1,000 children in California who are participants in an ongoing statewide study funded by the National Institutes of Health.

But he also found that the continued cleaning was working — at least for lead. For both parents and children, the levels of lead in their hair began to decline after they returned home and as they steadily moved bags of contaminated belongings to the curb and Mr. Van Ness continued his compulsive cleaning.

The presence of these metals does not mean the family will necessarily become ill, Dr. Arora cautioned. “But it does show that their bodies absorbed contaminants during that period, exposure that scientists associate with increased risks of neurological and developmental harm and, in the case of arsenic, cancer,” he said.

All 10 experts who reviewed the testing results from the house expressed concern about the level of contamination and said that the insurance-led remediation effort was not sufficient. Several of them highlighted the risk in the attic, where testing by The Times detected beryllium, chromium and cadmium, all known to cause cancer in humans.

Especially concerning is beryllium, said Dr. Michaels, who issued the standard for beryllium during his tenure as the longest-serving administrator of OSHA. “There is no safe level of beryllium exposure,” he said, describing how, at the Department of Energy, an accountant had developed the debilitating lung condition known as chronic beryllium disease after handling files stored in a building where beryllium had been processed years before.

“The most shocking thing is that this is after the home was remediated,” said Joseph G. Allen, the director of the Healthy Buildings Program at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a former scientific adviser to the White House, who reviewed the results.

“Junk Science”

What happened to the Van Ness family is unfolding across the Los Angeles basin, as homeowners navigate a narrow range of options: accept a modest cleanup or shoulder the cost themselves. Or, most fraught of all: move back in and accept their insurers’ assurances that the air is breathable, the walls are clean and the home is safe, according to responses to a Times survey of more than 500 survivors of the recent fire, as well as interviews with three dozen affected families.

Evidence showing that the remediation approved by insurers is inadequate is mounting: Data from 45 homes tested after professional cleaning showed that 43 of them still tested positive for unsafe levels of lead, according to Eaton Fire Residents United, a coalition of concerned residents.

Farmers ultimately paid for the Van Ness family’s hotel accommodation for seven months and approved a budget of $25,900 to have the home professionally cleaned — a fraction of what it would have cost to follow the advice of experts who insisted that the only way to remove the contaminants was to strip away every surface the smoke touched. That kind of renovation would have cost upward of $500,000, according to data from the real estate tracking firm Cotality.

Scale those numbers across the Los Angeles burn zone, and the math is staggering: Doing only a surface-level cleanup of the nearly 10,000 homes that likely had smoke damage would save insurers over $8.5 billion, according to a Times analysis using Cotality data.

“The first commandment of an insurance company is, ‘Pay as little as possible and as late as possible,’” said John Garamendi, a Democratic congressman who represents Northern California and who was the state’s first insurance commissioner in 1991.

Dylan Schaffer, a lawyer who is representing more than 500 policyholders whose homes were damaged by toxic smoke from the Los Angeles fires, agreed that the insurers are driven by the bottom line. “There is no other explanation. The science is against them.”

It was when the Van Nesses started asking about the science that they ran into problems with Farmers.

Five years ago, Ms. Pineda was diagnosed with Stage 3B cancer. Concerned that she could be exposed to carcinogens inside her house after the fire, her oncologist wrote a letter to Farmers urging the insurer to replace all the soft goods — including mattresses, bedding and carpets — according to correspondence reviewed by The Times.

The adjuster texted back: “Did the oncologist perform any type of testing of these soft goods to support their recommendation?”

The question landed like a blow — as though her doctor’s warning didn’t count unless it came with results from the very tests the family had asked the insurer to perform.

“It felt like when you have those dreams that something’s happening,” she said, “and you’re screaming at the top of your lungs in your dream to wake someone up or to alert someone, and nothing is coming out.”

In California, insurers began trying to limit payouts for smoke damage more than a decade ago, after a series of devastating wildfires, according to Dave Jones, a former state insurance commissioner who was the top regulator when carriers first started inserting policy language that excluded toxic smoke.

When those exclusions were struck down in court, the carriers turned to something more subtle: They downplayed the science by relying on in-house experts, whose studies are often not peer-reviewed and whose methods are increasingly at odds with the emerging science of urban wildfires, according to interviews with two former insurance commissioners, insurance industry whistleblowers, attorneys and consumer advocates.

The initial settlement letter that Farmers sent to the Van Nesses, which was reviewed by The Times, referred to “scientific studies” that it said showed that household materials exposed to the smoke could be cleaned. According to these studies, it said, soot, char and ash have “no inherent physical or chemical properties that will cause physical damage to common household materials,” and that “routine laundering” and “everyday cleaning methods” were enough to restore the home to its pre-fire state.

In a single footnote, the letter referred to only one source: a three-page paper from 2019. It appeared on the website of a private company specializing in hazardous materials that once employed Richard L. Wade, the paper’s author.

Contacted by The Times, Dr. Wade confirmed that the document was never published nor peer-reviewed and described it not as a study but as “a research summary,” contradicting how Farmers characterized it.

“This report is not objective science,” said Dr. Michaels, currently a professor at George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health, after reviewing the paper. “It makes unsupported and unverifiable assertions,” he said, adding, “It’s science for hire.”

Dr. Wade did not respond to questions regarding the criticism of his research paper.

In an email, Luis Sahagun, a spokesman for Farmers Insurance, wrote: “Every claim is evaluated and reviewed on an individual basis. Our goal is to pay claims quickly and fairly, taking into account the circumstances of the loss and the terms of the policy.”

The company did not address detailed questions from The Times about the contamination found inside the Van Ness home after the insurer-led remediation, or about the carcinogens detected in the family’s hair, saying that “we cannot comment on individual claims or customers.”

When the family sent their independent results to Farmers in June, the insurer turned to Safeguard EnviroGroup, a company that is advising the leading insurance carriers in California following the fires, and whose principal scientist is Dr. Wade, the expert whose paper was not peer-reviewed but was used as a reference.

In a document labeled “confidential” and obtained by The Times, Safeguard EnviroGroup’s founder, Brad Kovar, sought to discredit the family’s independent report, writing that the hygienist hired by the Van Nesses lacked a particular license, and that the report — which found the highest levels of lead in the attic — had failed to specify whether the samples came from a floor, a shelf or a windowsill, each of which has a different regulatory threshold.

In their denial letter to the family, Farmers, citing the report by Safeguard EnviroGroup, further described the attic as a “non-habitable space” — the only explanation the insurer provided for never having tested the attic for contaminants.

But in response to a detailed list of questions, a spokesman for Mr. Kovar seemed to contradict that guidance, saying that “all non-habitable spaces are relevant if they meet established contamination thresholds and provide pathways of exposure.”

The spokesman added: “Our conclusions are based on fact, data, established methodologies and recognized scientific standards.”

Dr. Nieusma pointed out that the HVAC is in the attic and acts as the “lungs of the house.” If the attic is contaminated, the HVAC is likely redistributing those toxic particles throughout the home.

“What they are doing is junk science,” said Dr. Zahid Hussain, winner of the Department of Energy Secretary’s distinguished service award for his work at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, adding that references to empty or unvetted studies are rife in the insurance industry when it comes to smoke.

The (Lack of) Standards

The Van Ness home, along with the debate over what the family’s insurer should have done to repair it, is a microcosm of a broader fight now dividing the American Industrial Hygiene Association, which publishes a technical guide for how to remediate smoke damage. In the absence of state or federal standards, insurers have cited this guide, which lists Mr. Kovar and Dr. Wade among its authors.

But a cohort of industrial hygienists say the guide has been hijacked by insurance industry contractors who have introduced language suggesting that toxins can be cleaned using everyday methods. This summer, the hygienists submitted to the A.I.H.A. a list of what they said were errors and distortions in the latest edition of the guide, arguing it should be retracted or significantly revised.

They said that numerous non peer-reviewed research papers had been added as references in the bibliography, while peer-reviewed studies showing that microscopic particles of smoke can penetrate the fibers of a house were removed or omitted.

On Dec. 16, the debate turned tense on a video call during which the A.I.H.A. declined to make changes, according to three participants on the call.

In an emailed statement, Jessie Lewis, an A.I.H.A. spokeswoman, declined to discuss the specifics of the meeting, saying that the technical guide was a “science-based publication” and that the most recent edition was not influenced by the insurance industry. She had no comment after The Times pointed out that the organization’s top donors included the Property Casualty Insurance Association of America, one of the main lobbying groups for the insurance industry.

The same battle is now roiling the newly created California Smoke Claims & Remediation Task Force, where Safeguard EnviroGroup employees including Dr. Wade presented slides claiming that professional cleaning was enough and that testing for anything more than lead, asbestos and soot, char and ash was an unnecessary “rabbit hole,” as first reported in a San Francisco Chronicle investigation. They argued that the A.I.H.A. guide — the same one that scientists are asking to be retracted — should be the accepted standard.

Since returning to their house in August, the Van Nesses have debated leaving for good. But where would they go?

Mr. Van Ness’s job provides the health insurance needed for his wife’s continuing cancer treatment with the oncologist who saved her life. And on his waiter’s salary, they feel trapped in one of the country’s most strained housing markets.

“It’s free-falling while reaching for branches that you hope will break your fall but don’t,” he said. “And so you flail. You paint, you rack up debt and get rid of the things that you think are dangerous, you keep windows open, you wash your hands more,” he said. “And you worry that your efforts are no match for what really needs to happen.”

For now, the Van Nesses are doing what they can: fighting with their insurer. And cleaning.

Methodology

Sample collection – With the family’s permission, The Times commissioned certified professionals and scientists to collect samples from the house and the family. Eleven wipe samples were taken from the house, including the attic and the family’s converted garage, using the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s 9102 sampling method: seven samples and one blank for lead; four samples and one blank for a broader metals panel. Additionally, air samples were collected using equipment from Access Sensor Technologies and Casella Solutions.

The Times commissioned an independent lab, Eurofins, to analyze the results, and the professional hired by The Times followed strict chain-of-custody procedures, documenting each step in the collection, handling and transfer of the samples to ensure their integrity and prevent contamination or tampering.

Lab analysis – For the wipe samples, the lab used Inductively Coupled Plasma (I.C.P.) Mass Spectrometry (M.S.), modifying the N.I.O.S.H. 9102 protocol to use a more precise analytical method, a step recommended by scientific advisors and senior researchers at the lab. Air samples were analyzed using three common analytical methods: I.C.P.-M.S., I.C.P.-Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (A.E.S.), and X-ray Fluorescence (X.R.F) Spectroscopy. The analysis of the air samples yielded inconclusive results. Experts agreed that detecting metals in the air would be difficult when collecting samples months after the fires, because the family ventilated the home and used air purifiers.

Results – Ten experts reviewed the lab results commissioned by The Times and compared them with the tests conducted by the contractor chosen by Farmers Insurance.

- Dr. Joseph G. Allen, a certified industrial hygienist and an associate professor of exposure assessment science at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, where he heads its Healthy Buildings Program.

- Dawn Bolstad-Johnson, a certified industrial hygienist who has tested more than 100 homes in the Los Angeles area.

- Dr. Jill Johnston, an associate professor at the University of California at Irvine’s Joe C. Wen School of Population & Public Health whose research focuses on the health impacts of environmental contaminants.

- Jeanine Humphrey, an industrial hygienist who has tested more than 100 smoke-damaged homes in Los Angeles.

- Dr. Zahid Hussain, a former division deputy of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the recipient of the Department of Energy Secretary’s Distinguished Service Award.

- Dr. Lisa A. Maier, a pulmonologist who leads a clinical team studying and caring for patients with chronic beryllium disease as chief of National Jewish Health’s Division of Environmental and Occupational Sciences.

- Peggy Mroz, lead epidemiologist in the Division of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences at National Jewish Health, who studies chronic beryllium disease.

- Dr. Joe L. Nieusma, a toxicologist and author of a recent study showing that particles of smoke saturate every crevice, seam and texture of a home and are recirculated through airflow.

- Dr. Michael Weitzman, a professor and former chairman of the department of pediatrics at the New York University School of Medicine, whose research on lead poisoning in children contributed to the decision by the E.P.A. to lower its dust lead clearance levels.

One expert asked not to be named because of fear of retaliation.

The following chemicals were detected in the home via wipe samples: lead, beryllium, cadmium, chromium, lithium and manganese. Some of these elements are naturally occurring in the body, but when found in extremely high concentrations they are harmful to human health and linked to neurological and developmental problems, as well as damage to specific organs, including the kidneys.

For surface wipe samples, the post-abatement federal hazard limit for lead is 5 µg/ft2 for floors, 40 µg/ft2 for window sills and 100 µg/ft2 for window troughs.

The following chemicals were found in the hair analysis at elevated levels when compared with median exposure levels of 1,000 children in California who are participants in an ongoing statewide study funded by the National Institutes of Health: zinc, strontium, phosphorus, manganese, magnesium, lithium, lead, copper, calcium, barium and arsenic.

Estimating damage from smoke – To estimate the number of homes that were likely smoke-damaged, The Times drew a 250-yard buffer around structures identified by Cal Fire as partially burned. This buffer was chosen based on the public health advisory issued by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health after the fires. It is a conservative measure: A National Academy of Sciences report stated that any property within one to 10 kilometers from a burned structure could be damaged by smoke, depending on the direction of the wind.

To estimate the $8.5 billion in savings for insurers to remediate the homes that have likely experienced smoke damage, The Times counted the homes within 250 yards of a burned structure. When a property had additional structures, like a guesthouse or a garage, the structures were all counted as one. For each property, The Times used a median cost of remodeling, excluding demolition — a metric provided by Cotality, a company that tracks and analyzes real estate.

Why hair sampling and not blood? – To date, 99.5 percent of residents tested by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health following the recent fires — all but 10 out of more than 2,000 people — had blood lead levels below the Centers for Disease Control’s ceiling of 3.5 micrograms per deciliter, meaning almost no one showed elevated levels despite widespread evidence of lead contamination. The Times turned to the technology created by Dr. Arora which uses hair strands because it maps past exposure over time.