The Diane Ladd Scene I Think About All The Time

More from Hung Up this week: I love the ending of Marty Supreme … 2025-in-review … and Have you checked on the Barb in your life?

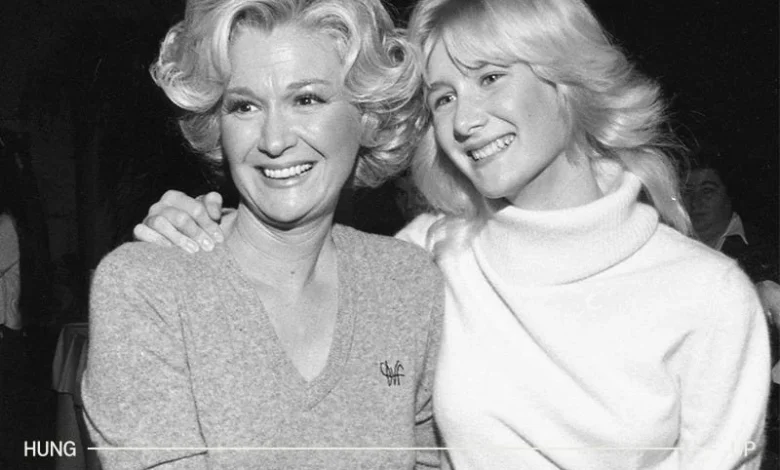

Diane Ladd and Laura Dern, circa 1980s (Photo: Ralph Dominguez/MediaPunch via Getty Images)

Sometimes writing this newsletter feels like I’m just trying to get everyone I know to watch Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. It’s such an underrated Scorsese movie! I’ve found ways to write about the movie, which stars Ellen Burstyn, twice in the last year. (I will probably write about it a third time when I finish my review of Mr. Scorsese.) “A movie for everyone who has ever dreamed of a second chance,” the poster reads, showing Burstyn and Kris Kristofferson tangled in a romantic embrace. Burstyn is a flailing, out-of-options widow when she puts her kid and her life in a station wagon and sets off for a fabulous singing career in L.A.; she makes it as far as waiting tables in Tucson.

But there are second chances in Tucson, and third and fourth ones too. Alice meets Flo, played by Ladd, a real bossy broad. She rolls her eyes at Flo’s jokes, and her face turns pink when Flo warns the regulars (all men) to leave the new waitress alone; If they’re going to grab an ass, Flo cautions, let it be hers. The women spar and then soften. Ladd, as Flo, is quick and sharp; her affection comes with a certain edge, too. She’ll never shortchange you, but she won’t bullshit you either. She reminds me of so many women I grew up with, so many women I wanted to be like. The ferocity of certainty, of direction, of purpose. Her life isn’t perfect, but she’s never afraid. It’s a gorgeous performance. In my head, she won an Oscar for it, and it was only a few weeks ago that I realized she hadn’t. I think about it all the time.

Ladd died last month, at age 89. The last few weeks have been busy, but I didn’t feel right ending the year without writing about this actor who meant so much to me. Alice is one of my favorite movies, but my mind immediately went to Ladd’s work on Enlightened, playing a cautious, sometimes cold mother to her real-life daughter, Laura Dern. (They acted together several times, in Wild at Heart, Rambling Rose, Citizen Ruth, and a small Dern had an uncredited role in Alice, too.) Enlightened is one of those shows that feels like a secret you never want to gatekeep. It was Mike White’s first HBO show, long before The White Lotus. I like the latter, but too often it becomes a series of screenshots engineered for online sharing. Enlightened, by contrast, is about complicated, bellicose people who always seem to end up disappointed by the people they love, by the world around them, by themselves.

Dern plays Amy Jellicoe, a woman who returns to work after a rehab stint following an in-office crashout. She leaves her program with beaded necklaces and linen clothes and mantras and affirmations; Enlightened is about how to live as a changed person when everyone around you is still the same. The first season’s fifth episode is one of the most moving half-hours of TV I can remember: Amy clashes with her own mother as she frets about a mother she hears about on the news who will soon be deported to Mexico, and as she is a last-minute invite at a baby shower thrown for a co-worker who doesn’t really want her there.

Amy’s car won’t start, and she asks her mother if she can use her sedan to drive to work. Her mom, Ladd, with nervous energy radiating off of her, says no, and reminds her daughter that she isn’t insured to drive it. Amy pleads with her mother, who is almost cruelly firm. Amy walks to the bus stop in the pouring rain. She asks a woman move her purse so Amy can use the seat. Hair dripping wet, clothes soaked through, Amy peers at her fellow passengers and frowns. “Some days you feel like the world is against you. And everyone around you seems so mean. And Ugly. There are times I just burn with hate,” Amy says in voiceover. “In those times, I am ugly too.” Enlightened is about resisting the urge to lose your temper, trying not to lash out, the dream of being not a different person, just a better one. “I don’t want to hate. I want to be kind, and wake in the kindness of others,” she says.

She’s reading a book about meditation that says if you look upon every person as having once been your mother, your heart will soften. Amy looks around at the passengers: a middle-aged woman with a Bluetooth in her ear, a surly teen, a man with locs, and a woman in a caftan. “She was my mother. When I was sad, she held me. My mother, who sacrificed so much for me, there she is. There she is. There she is. She is all around me.” The camera holds on all of these people, and eventually replaces some of them with Ladd’s face, lips pursed and tense. Amy looks at her longer. Maybe the book means someone else’s mother, her frown seems to say.