How the Supreme Court’s Work to ‘Bolster Executive Power at Congress’s Expense’ is Coming Back to Bite

President Donald Trump launched his second term by seeking to usurp Congress’ authority and challenge a nearly century-old legal precedent that shields independent executive branch agencies and the congressionally-confirmed officers who lead them from presidential overreach. In late January, Trump removed Gwynne Wilcox from the National Labor Relations Board and fired two commissioners of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. In February, he dismissed a member of the Merit Systems Protection Board. And in March, he axed two commissioners from the Federal Trade Commission.

Nearly a year after this push began, the Supreme Court on Wednesday will hear oral arguments on whether Trump can continue his crusade against independent agencies and the laws Congress passed to protect them by exerting control over the Federal Reserve. The case centers around Fed Governor Lisa Cook, who Trump in August attempted to remove based on contrived — and seemingly baseless — mortgage fraud allegations and without due process. Cook sued, and a lower court in September halted her removal while her case moved through the legal system. The case has now reached the Supreme Court on its emergency docket.

The world will be watching as the Court considers Trump’s self-granted prerogative to bulldoze Congress in order to assert his own political will over a central bank that is critically important to the global economy.

Cook’s case is about maintaining Federal Reserve independence, protecting consequential monetary policy from presidential influence and partisan policy setting. It’s also about the ways in which Trump throughout the first year of his second term has crushed congressional authority and concentrated more and more power within the executive branch. To understand how Trump’s attempted overreach into the Federal Reserve fits in with his administration’s themes of unilateral executive power requires an understanding of the wonky world of independent agencies created by Congress.

The crux of the pre-Trump definition of independent agencies is that Congress designed them to be insulated from partisanship, and the president does not control them.

“If, as the president insists, he is able to remove a Federal Reserve governor for seemingly any reason at any time with no due process,”Jeremy Kress, an associate professor of business law at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business, told TPM, “that effectively nullifies the removal protection that Congress put in place and would bring the Fed under direct presidential control.”

Independent agencies consist of bipartisan, multi-member bodies whose members serve for staggered, multi-year terms. Presidents appoint the members and agency heads, all of whom ultimately must be confirmed by the Senate. These agencies exist within the executive branch but outside of the purview of the president, primarily because Congress installed protections to shield board members and agency officers against frivolous presidential removal. Members and heads of independent agencies, the law states, can only be removed “for cause.”

In 1935, a different set of Supreme Court justices upheld this principle, ruling in a case known as Humphrey’s Executor that Congress has constitutional authority to restrict the president’s ability to fire members and leaders of independent agencies.

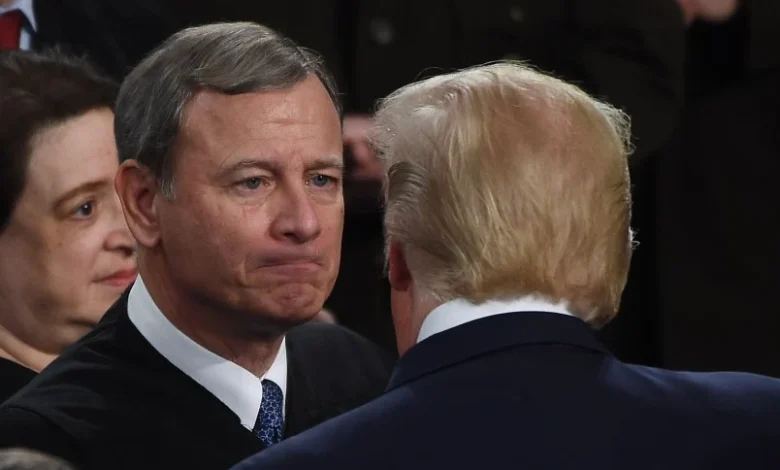

But today’s Roberts Court, with its 6-3 conservative majority, has time and again moved to ignore or revoke Congress’s constitutional reins on the president and instead leaned ever more toward embracing the concept of a unitary executive, wherein the president dominates the entire executive branch.

“The big global picture here is that this Supreme Court has been very intent and acted to bolster executive power at Congress’s expense,” Sarah Binder, a political science professor at George Washington University, told TPM.

The Supreme Court justices have in recent years fondled the idea that the Federal Reserve is a special entity, shielded from presidential interference in a way other independent executive branch agencies, even ones that deal with economic policy, are not. In 2018, then-federal appeals court Judge Brett Kavanaugh wrote a dissent against a ruling that protected the constitutionality of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. In it, he said the Fed had a “unique function … with respect to monetary policy.” Justice Samuel Alito in a separate, 2024 case challenging the CFPB, CFPB v. Community Financial Services Association of America, highlighted the Fed’s self-reliant funding structure and “unique historical background.” In the spring 2025 case challenging the removal of the NLRB and MSPB officers, the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution gives the president authority to remove independent agency board members by reasoning that they likely “exercise considerable executive power” on the president’s behalf. SCOTUS then alluded to its intention to protect the Federal Reserve, calling the Fed “a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity,” and highlighting the legacy of other historic U.S. banks.

Now, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority has put itself in an awkward position on the Cook case, where it must choose either to prove that the Fed is not the same type of entity as the others the Court has allowed Trump to gut, or greenlight Trump’s attempt to remove Cook. Allowing Cook’s removal will give a stamp of approval to the president’s open threats to effectively rule the Fed with potentially devastating consequences.

That the Supreme Court is even hearing oral arguments or received full briefings on this emergency docket case is unusual, said Binder, and signaled that the court might be fidgety about the implications of its past rulings that uphold Trump’s unilateral control over executive branch agencies.

“That’s really what the struggle is here, because [in] the legal rules they’ve been laying out or suggesting, there’s no exception for an agency just because it’s really important,” said Binder, who co-authored a book about congressional governance of the Fed.

“The courts basically muscled Congress out here and said, ‘No. We’re going to decide this question,’” Binder said.

When the Department of Justice subpoenaed the Fed, part of an investigation into whether Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell lied to Congress while testifying about the cost of renovations of two Fed buildings, the Trump administration may have overplayed its hand. Legal and financial experts saw the investigation as a transparent bid to pressure Powell specifically, and Fed leadership more broadly, to align its monetary policy with the president’s wishes. That will be top of mind for justices at Wednesday’s oral arguments, experts told TPM.

“There’s no question that the announcement of that investigation is going to hang over the Lisa Cook case,” Richard Pildes, a constitutional law scholar and NYU professor of law, told TPM. “I doubt that action has helped the government’s position.”

If the Court decides Cook’s case with a narrow ruling that doesn’t address broader questions of Fed independence, Michigan’s Kress said, Congress could act legislatively. That’s a longshot, given that it would require more than a dozen GOP senators to join with Democrats for a veto-proof majority.

But at least in the case of the Powell investigation, Congress has shown signs of life. Senators from Trump’s own party vowed to block any of the president’s nominees to the Federal Reserve, including the president’s candidate to chair the board when Powell’s leadership term ends in May. (He can remain on the board as a governor until 2028.)

“We’re seeing what Congress can do,” said Binder, “and specifically what the president’s party can do in the Senate, given that those are the folks who will make or break the president’s ability to appoint a new chair [and] fill up the board with people who are going to be more amenable to his pressure for a lower rate.”