Five things we learned from the 2026 Baseball Hall of Fame election

Editor’s note: Got Hall of Fame questions? Submit them here for Jayson Stark’s subscriber mailbag.

COOPERSTOWN, N.Y. — Center field. Can we all agree it’s still the most romanticized position on the baseball diamond? Maybe that explains why it’s been the toughest to crack on Hall of Fame election night.

Bet you didn’t know that, according to Baseball Reference, more than 3,000 men have played center field in the major leagues in the modern era. Yet only eight of them had ever been elected by the writers to the Baseball Hall of Fame … until now.

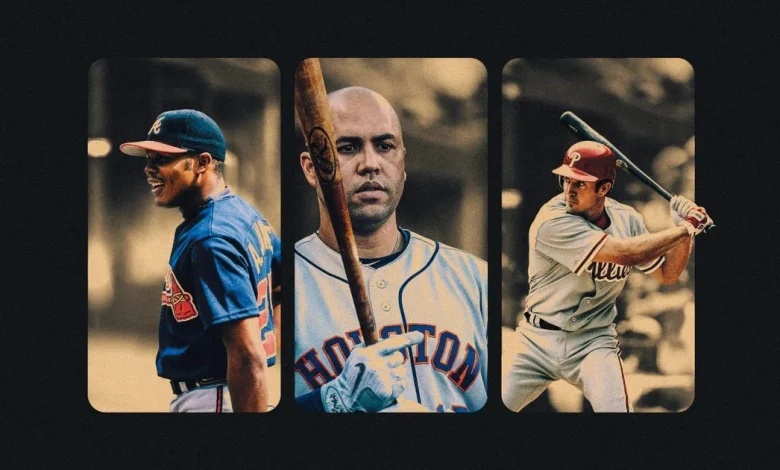

On Hall of Fame election night Tuesday, the writers did something they’d never done before. They elected two center fielders to the Hall in the same election. There was Carlos Beltrán, elected in his fourth try with 84.2 percent of the vote. Joining him was Andruw Jones, elected in his ninth year on the ballot, with 78.4 percent. Jones cleared the 75-percent bar by only 14 votes.

So this was a Hall of Fame election unlike any other. Let’s reflect on why that is for a moment.

• It’s about time the center-field wing of the Hall got some new blood. Before this election, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America had elected only two true center fielders — Ken Griffey Jr. in 2016 and Kirby Puckett in 2001 — in the previous 45 years. Then these two guys arrived in the same year.

• When a Hall of Fame center fielder comes along, we normally know one when we see one. Of the previous eight center fielders elected by the writers, five of them sailed in on their first try, and a sixth (Tris Speaker, in 1937) was a second-rounder. So before this election, there’d been only two center fielders elected in the fourth round or later — Joe DiMaggio (in his fourth try, believe it or not, because 1955) and Duke Snider (11th). Then we had two more added to this club on one night.

• Let’s remind you again how rare that is: This was just the fourth time, in nine decades of Hall elections, that the writers elected any two non-pitchers in the same year who had played the same position. The others:

2009 — (Left field) Rickey Henderson and Jim Rice

1982 — (Right field) Henry Aaron and Frank Robinson

1952 — (Right field) Harry Heilmann and Paul Waner

• And one more thing: Since annual Hall voting began six decades ago, this was only the second time the writers elected two players in the same year, at any position, who had each bounced around the ballot for at least four years. And the other time was 50 years ago, when Robin Roberts (fourth round) and Bob Lemon (11th) got the call in 1976.

So Beltrán and Jones have already changed the landscape of modern Hall of Fame voting. But there is so much more to kick around. So here come … Five Things We Learned from the 2026 Hall of Fame Election.

PlayerVotesPercent

Carlos Beltrán

358

84.2

Andruw Jones

333

78.4

Chase Utley

251

59.1

Andy Pettitte

206

48.5

Félix Hernández

196

46.1

Alex Rodríguez

170

40

Manny Ramírez

165

38.8

Bobby Abreu

131

30.8

Jimmy Rollins

108

25.4

Cole Hamels

101

23.8

Dustin Pedroia

88

20.7

Mark Buehrle

85

20

Omar Vizquel

78

18.4

David Wright

63

14.8

Francisco Rodríguez

50

11.8

Torii Hunter

37

8.7

Ryan Braun

15

3.5

Edwin Encarnacíon

6

1.4

Shin-Soo Choo

3

0.7

Matt Kemp

2

0.5

Hunter Pence

2

0.5

Rick Porcello

2

0.5

Alex Gordon

1

0.2

Nick Markakis

1

0.2

Gio González

0

0

Howie Kendrick

0

0

Daniel Murphy

0

0

1. Bang the trash can faintly! Is Beltrán’s election telling us voters don’t care about that type of “cheating”?

Despite his involvement in the Astros’ sign-stealing scandal, Carlos Beltrán sailed into the Hall on his fourth try. (Bob Levey / Getty Images)

So do we care about cheating or not? From the moment Beltrán first showed up on this ballot in 2023, I’ve been trying to make sense of that question.

On one hand, we lived through the performance-enhancing drugs era, where hundreds of voters proudly wouldn’t vote for any “cheaters.” So why did this group just elect a player who was named, in Rob Manfred’s official commissioner’s report on the 2017 Astros, as the central clubhouse figure in Trash Can-gate?

What a fascinating question, huh? It seems clear now that Beltrán got dinged in Year 1 by these voters for his role in that scandal. But if that was just a one-year phenomenon, why did it take him four elections to clear this bar?

Look at the voting trends — In case you hadn’t noticed this, we’d almost reached the point where there was no such thing as a fourth-ballot Hall of Famer anymore. Beltrán is only the second player elected in (exactly) the fourth round in the last four decades. There was Mike Piazza in 2016. And before him, the last fourth-rounder was Harmon Killebrew, in 1984.

What does that tell us? For one thing it’s reminder that a massive percentage of the recent Hall population has been no-doubters elected on the first ballot. Of the 29 players voted in by the writers since 2014, 18 of them were first-timers. And only 28 percent (eight of 29) had to wait beyond three years.

So if it took Beltrán four tries, that tells us, I think, that we had quite a few holdout voters who needed more time to warm up to the idea of Carlos Beltrán, Hall of Famer. But now that he’s in, let’s ask …

Was it just the anti-cheating crowd that flipped? For insight into that question, I turned to my friend Jason Sardell, the most accurate Hall of Fame voting projector I know. He looked at voters we could define as “anti-PED” and then tried to determine how many of them voted for Beltrán.

He did that by basically dividing voters into two categories. And what was the litmus test? Voters who voted for both Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens in their last year on this ballot (2022) went into one group. Let’s call it the Cheating Isn’t a Thing voting bloc.

The other group was voters who voted for neither Bonds nor Clemens that year. They’re essentially the Keep the Cheaters Out of the Hall voters.

And here’s a reminder that both of those groups had lots of members. More than 250 writers voted for both Bonds and Clemens. About 130 voted for neither.

What Sardell found, at least among voters who have publicly revealed their ballots, tells us a lot about how Beltrán pulled this off.

As you’d expect, he’s been reeling in virtually all the votes (93 percent) from the Cheating Isn’t a Thing crowd this year. But with about half the total ballots revealed publicly, Beltrán was also racking up 50 percent of the votes from writers who voted for neither Bonds nor Clemens.

To put that in better perspective, let’s also look at this over a larger sample (Years 2, 3, 4 on the ballot). Here is what Sardell found:

A big development has been Beltrán’s growing support from the group you would most expect — writers who once voted for both Bonds and Clemens.

2023: 66 percent

2024: 74 percent

2025: 87 percent

2026: 93 percent

What’s even more revealing, though, is that Beltrán has basically quadrupled his votes from Keep the Cheaters Out voters, meaning writers who weren’t voting for either Bonds or Clemens in their final year. Maybe, on second thought, we need to rename that group.

2023: 13 percent

2024: 25 percent

2025: 42 percent

2026: 50 percent

(Source: Jason Sardell)

So we can see how Beltrán got from 46.5 percent in Year 1 to the cusp of election. But even his newfound support from “anti-cheater” voters doesn’t fully explain how he finally made it to the finish line. So what pushed him over the top? He should probably thank all the writers voting for the first time. More on their role in this shortly.

The funny thing is that every one of these new voters was covering baseball while those Astros trash cans were clanging — but they overwhelmingly voted for Beltrán anyway. There’s a statement on the evils of cheating (or lack thereof) somewhere. Don’t you think?

2. Is Andruw Jones now the biggest mind-changer ever?

Andruw Jones garnered only 7.3 percent of the vote in 2018, but now he’s a Hall of Famer. (Brian Bahr / Allsport)

David Copperfield once made the Statue of Liberty disappear. Andruw Jones once made about 1,000 doubles disappear. Are we sure that Statue of Liberty trick should rank No. 1 on this list?

Now, Jones may have pulled off his greatest magic trick of them all. He just made more than 300 Hall of Fame voters change their minds. Let’s trace that transformation for you.

In 2018, only 31 voters (just 7.3 percent) checked the box next to Jones’ name in his first go-round on this ballot — which means 391 writers didn’t vote for him. Think about that. Think about how far away from this moment Jones was back then. Even if he’d figured out a way to get 10 times as many votes, he still wouldn’t have had enough to get elected.

Also, mull this over: Incredibly, 18 players got more votes that year than he did. And if he’d gotten just 10 fewer votes and fallen below the 5 percent threshold, he’d never have stayed alive for a second ballot, let alone been elected. So what about that said that by 2026, we’d be living on a planet where this guy was a Hall of Famer?

No need to go down that trail, because by Tuesday night, Jones’ vote total had grown slightly since then … by just over 300 votes. He was all the way up to 333 votes in this election. And that means he has now made history.

Want to guess how many other players have been that close to careening off the ballot in their debut year and then roared all the way back to get elected in some future year? Right you are. That would be none.

Try to comprehend how hard it is to get more than 300 voters to change their minds — especially in an election where only 400-plus writers vote? We can measure just how hard that is with this handy list, of players who attracted the lowest first-year vote percentages but later got elected by the writers:

PLAYERFIRST YEAR FINAL YEAR

Andruw Jones

7.3%

78.4%

Scott Rolen

10.2%

76.3%

Billy Wagner

10.5%

82.5%

Todd Helton

16.5%

79.7%

(Source: MLB Network Research)

If we’re just counting votes instead of percentage points, Jones wound up adding 302 votes between his first and last years on the ballot. That would be the mostn since players’ time on the ballot shrank from a maximum of 15 elections down to 10 in 2015.

But that leap was actually even harder than it looked. Jones was still at only 7.5 percent as late as 2019. Then he headed for the launch pad and rocketed all the way up to 58.1 percent by 2023, adding nearly 200 votes in just four years.

So he was only 66 votes away from getting elected at that point. He was a lock, right? Wrong. It took him three years to find those votes. Where did they come from?

What Sardell found was that most of the “Big Hall” — and even “Medium Hall” — voters had already come around on Jones. So to round up those final 35 votes or so he needed this year, he had to make inroads with the “Small Hall” crowd (generally those who vote for no more than five players).

Over the previous two elections, some of those Small Hall voters were actually dropping him, which felt like an ominous sign. But this was a very different year, because Ichiro Suzuki, CC Sabathia and Billy Wagner opened so much space on the ballot by getting elected a year ago.

So Jones was well-positioned as one of the new options for Small Hall voters whose normal M.O. is to vote for the top two to four names on the menu. For his first eight rides on this carousel, it was hard to rank Jones in any voter’s top two or four. This year, that changed.

But surprisingly, Sardell found Jones has flipped only a handful of those voters this year. Of the first 12 public voters who went from no to yes on him, just six were writers who had no more than one holdover returning from their ballots a year ago. The other Small Hall voters had plenty of room to add him — and still said no thanks. It’s fair to assume that at least some of those “no” voters are taking that stance because of his disturbing 2012 domestic-violence arrest, which would give anyone pause.

Regardless of their reasoning, though, that failure to make bigger gains with that Small Hall crowd meant Jones still needed to find more votes somewhere. So where did he find them? With the same first-time voters who helped carry Beltrán over the finish line.

We’ll dig deeper into how they both fared with that group shortly, because, as you’ll see later in this column, first-time voters influenced this election in more ways than you’d think.

3. Ready for a big Utley/Félix/Pettitte Induction Day in 2028?

Félix Hernández took a massive year-over-year leap in the voting. (Stephen Brashear / Getty Images)

Sometimes, the most interesting stuff that happens on Hall of Fame election night doesn’t even involve the players who get elected. It’s the players who come flying up the board to make the biggest jumps — because there’s always a story attached to those leaps. So here’s this year’s leaderboard.

PLAYERINCREASE20262025

Félix Hernández

25.5%

46.1%

20.6%

Andy Pettitte

20.6%

48.5%

27.9%

Chase Utley

19.3%

59.1%

39.8%

Carlos Beltrán

13.9%

84.2%

70.3%

Andruw Jones

12.2%

78.4%

66.2%

Bobby Abreu

11.3%

30.8%

19.5%

So what’s up with those wild pole vaults by Félix Hernández, Andy Pettitte and Chase Utley? Let’s look closer.

There’s a throne in Cooperstown for the King – King Félix is doing it again. A decade and a half ago, he was the ground-breaker who changed Cy Young Award voting forever. Now he has turned his sights to Cooperstown.

Fifty years ago, Bob Gibson would have laughed out loud if you’d told him a starting pitcher could have a won-lost record of 13-12 and win a Cy Young Award … but Hernández actually did just that in 2010. Cy Young voters have pretty much ignored the win column ever since.

So is the King now about to similarly alter the Hall of Fame voting scene? Sure looks like it.

Is there really room in the plaque gallery for a Hall of Fame starter who won only 169 games and was essentially done as a productive pitcher at age 31? Well, there hasn’t been since Sandy Koufax walked off into the sunset 60 years ago. But all those King Félix voters out there don’t care what happened in those last six decades.

We can see that clearly because, before this year, only one player in the history of Hall of Fame voting — Luis Aparicio — had ever spiked his vote total by this large a percentage (25.5%) from one year to the next. Once again, Hernández is rewriting history.

BIGGEST ONE-YEAR VOTE JUMPS

PLAYERJUMPYEAR 1 YEAR 2

Félix Hernández, 2026

25.5%

20.6%

46.1%

Luis Aparicio, 1984

25.5%

41.9%

67.4%

Barry Larkin, 2012

24.3%

62.1%

86.4%

Gil Hodges, 1970

24.2%

24.1%

48.3%

Nellie Fox, 1976

23.8%

21.0%

44.8%

(Source: Jay Jaffe / FanGraphs)

Hernández also became just the third player ever to add more than 110 votes from one election to the next. The only others were Barry Larkin, who added an astounding 134 between the 2011 and 2012 elections, and Jim Rice, who jumped by 111 from 1999 to 2000. But almost 600 writers voted in that Larkin election and about 500 voted in Rice’s year, while “only” 425 cast votes in this election.

That list above feels like an unusual collection of names, and Hernández feels like an unexpected ground-breaking figure. But this is one of those years where a bunch of writers who used up all 10 spots last year had a lot more room this time. So Hernández became the biggest vote-grabber among that group.

Of the first 200 or so publicly revealed votes on Ryan Thibodaux’s Hall of Fame tracker, Sardell found that 44 percent of Hernández’s new votes had come from writers who voted for 10 last year and didn’t have room for him. Full disclosure: I was one of those voters.

But does this jump mean he should start writing his induction speech? Let’s go with yes on that. Everyone joining him on that chart above made it to the Hall eventually, although Gil Hodges and Nellie Fox had to do so through some version of the Veterans Committee.

Here’s a different way to look at it: In the last 40 elections, two other pitchers jumped to a vote percentage between 45 and 60 in their second year on the ballot: Don Sutton (in 1995) and Phil Niekro (in 1994). Both got elected by the writers exactly three years later.

So how does a Miguel Cabrera/Joey Votto/Zack Greinke/Félix Hernández Induction Weekend sound in 2029? I’d be happy to show up for that one!

Cut to the Chase — So when is Chase Utley’s Induction Weekend? Oh, it’s coming. We know that now. Maybe he joins Buster Posey on the podium next year. Maybe he’ll be keeping Albert Pujols company in 2028. But when a guy keeps making those double-digit voting jumps every year, you don’t need an MBA to do that math.

Year 1 (2024) — 28.8 percent

Year 2 (2025) — 39.8 percent

Year 3 (2026) — 59.1 percent

That’s a vote pattern that leads directly to Cooperstown. You know who could tell Utley all about that? A guy named Billy Williams.

It’s been a long time since Williams was hanging out with Ernie Banks at Wrigley Field. But we bring him up because he’s the only player in the history of annual voting who has followed this path — a debut year on the ballot in the 20s, a jump to around 40 percent in Year 2, then another jump above 50 percent in Year 3. Take a look.

WILLIAMSUTLEY

YEAR 1

23.4%

28.2%

YEAR 2

40.9%

39.8%

YEAR 3

50.1%

59.1%

So then what? Williams barely missed getting elected (by four votes) two years later, then cruised in by zooming all the way up to 85.7 percent in his sixth year on the ballot. Will it even take Utley three more years? All I know is this: It’s the third year I’ve written about Utley in this column, and I’ve had the same prediction all three years:

Chase Utley is going to be a Hall of Famer. Have I ever missed on one of these predictions before? Please don’t answer that!

Pettitte for the … Wynn — Just when Andy Pettitte had gotten used to the idea that he wasn’t going to be a Hall of Famer, these last two elections happened. They’ve gone slightly different than his first six!

First six elections — Got between 9.9 percent and 17 percent in all six — and was as low as 13.5 in Year 6.

Years Seven and Eight — Suddenly rocketed to 27.9 percent last year, then to 48.5 percent this year.

So what’s that all about? Well, last year was all about the arrival on the ballot of his old Yankees teammate, CC Sabathia. Let’s just say their numbers bore a certain similarity.

PITCHERW-LWARERA+

Pettitte

256-153

60.2

117

Sabathia

251-161

62.3

116

(Source: Baseball Reference)

By the time that revelation sank in, Pettitte found himself adding more votes last year than any other player on the ballot. And once a player becomes That Guy, it’s amazing how his train can start gathering steam.

The voting data suggests he’s a lot like King Félix. A large group of Big Hall voters suddenly had room on their ballots — and Pettitte started showing up on almost all of them.

According to Sardell, nearly 40 percent of Pettitte’s new votes came from the Big Hall/vote-for-10 crowd. Of the first 56 publicly available ballots with 10 names checked, Pettitte got a vote on all but four of them! (If you’re curious, Utley was on all but one, and Hernández wasn’t checked on only five.)

So does this mean Pettitte has a shot to get elected before he runs out of time after 2028? Not impossible. Since the dawn of annual voting, only one other starting pitcher (with eligibility remaining) jumped from the 20s to the 40s, in percentage of the vote, between one election and the next. That was Early Wynn — who went from 27.4 to 46.7 percent — in 1970. What did that portend? He got elected two years later.

On the other hand, Pettitte has only two elections left, and he would have to buck one of the strangest historical trends in the annals of Hall voting. Weirdly, no left-handed starter has ever been elected after his sixth year on the ballot. Lefty Grove (Year 6) set that bizarre record, in 1947.

Finally, there’s one more roadblock in Pettitte’s path. That would be his hazy PED cloud, which stems from a mention in the Mitchell Report and his subsequent admission that he briefly used human growth hormone (HGH) to recover from an injury. How big a hurdle is that? Hard to guess.

In a column I wrote last year, I explained why I vote for him anyway. Like many voters, I draw a line between PED eras — depending on whether a player’s PED “crimes” came before or after the arrival of testing. Pettitte falls in the pre-testing group. So why did I vote for him but not Álex Rodríguez, Manny Ramírez or Ryan Braun? That’s why.

But here’s one more intriguing wrinkle: Pettitte admitted to obtaining HGH from Brian McNamee, the same personal trainer linked to Roger Clemens. That was enough to keep Clemens from getting elected. But according to Sardell, 24 percent of the public voters who left Clemens and Bonds off their ballots in their final years did cast a vote for Pettitte this year.

So what should we take away from all that? You tell me. It’s been nearly 20 years since the Mitchell Report — and we’re still trying to figure out what to make of it. And here you thought Hall of Fame voting was a fun, easy job, huh? Not!

4. New voters made a major impact

Chase Utley was among the players who benefited the most from the wave of new Hall voters. (Hunter Martin / Getty Images)

There has never been a Hall of Fame election like this. So why is that, you ask? Because it isn’t every year that more than 50 new voters participate in the process, but it happened this year, according to Anthony Calamis, one of the great minds that works on the Hall of Fame Tracker.

The reason? Ten years ago, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America changed its rules to allow more writers from a newfangled invention called “the internet” to join the band. Crazy concept, I know, but hey, progress marches ever onward, even in the BBWAA.

The biggest chunk of new members came from MLB.com, which of course was (and is) covering all 30 teams. Now, a decade later, all those then-new members became eligible to vote for the Hall, because they’d put in 10 continuous seasons covering baseball — and that’s how the eligibility rules work.

According to my friends at the Hall of Fame tracker, that means about two dozen new voters came from MLB.com alone, plus several more who once worked there and now write elsewhere. There are approximately 20 other new voters, many of whom became eligible because they worked at other websites. So think about the impact that big a group can make.

Imagine how different a presidential election might work if a new state, around the size of Texas, got dropped into the electoral college. That’s kind of what happened here.

The final numbers showed that the total number of voters (425) increased by a smaller amount — in this case 31, up from 394 last year. Attrition is one reason that number isn’t larger. The other is the growing number of writers who used to vote and now have decided, for various reasons, that they don’t want to anymore.

But it’s those first-time voters, who think differently from longtime voters, who have hit this particular election like an earthquake. As of Sunday, the Hall voting tracker had logged the ballots of 36 of those new voters who had made their votes public. We’ll sum up their impact with two different sets of charts.

First, let’s look at just their raw vote totals and percentages.

PLAYERS THEY’VE HELPED

Beltrán: 36-for-36, 100 percent

Jones: 33-for-36, 91.7 percent

Utley: 30-for-36, 83.3 percent

Hernández: 27-for-36, 75 percent

Pettitte: 25-for-36, 69.4 percent

Abreu: 20-for-36, 55.6 percent

Cole Hamels: 18-for-36, 50 percent

Mark Buehrle: 15-for-36, 41.7 percent

PLAYERS THEY’VE HURT

Omar Vizquel: 2-for-36, 5.6 percent

Torii Hunter: 3-for-36, 8.3 percent

Jimmy Rollins: 5-for-36, 13.9 percent

David Wright: 8-for-36, 22.2 percent

Dustin Pedroia: 10-for-36, 27.8 percent

(Source: Hall of Fame Tracker)

But now let’s look at this another way. How much bigger (or smaller) would the current vote percentages of these players on the Hall Tracker be than where they’d stand if we excluded all the first-time voters? Here are Sardell’s calculations, after about half of the total votes had been revealed publicly.

PLAYERS THEY’VE HELPED

Beltrán: +2.4 percent

Jones: +1.8 percent

Utley: +3.5 percent

Hernández: +3.6 percent

Cole Hamels: +4.1 percent

Mark Buehrle: +3.6 percent

Pettitte: +3 percent

Abreu: +2.9 percent

PLAYERS THEY’VE HURT

Jimmy Rollins: -2.6 percent

Torii Hunter: -0.5 percent

Omar Vizquel: -1.2 percent

Dustin Pedroia: even

David Wright: +0.2 percent

(Source: Jason Sardell)

I never promised there would be no math. But here’s the simplest way to explain what that means: Without the overwhelming support from those new voters, Jones’ percentage of the vote would have dropped by nearly 2 percentage points, by Sardell’s calculations. Now look again at his final vote tally (78.4 percent), subtract 2 percentage points and what did you learn?

He’d have been looking at a much closer call without all his new best friends on the BBWAA’s 2026 voter rolls.

5. The Great PED Debate is almost over

Manny Ramírez got 38.8 percent of the vote in his final time on the writers’ ballot. (Jim McIsaac / Getty Images)

Let’s all take a moment to wave a fond farewell to Manny Ramírez. It was his 10th year on this ballot — and his last.

He never came within 150 votes of getting elected. He got just 38.8 percent of the vote. So we wish him luck with the era committee. As Bonds and Clemens could attest, he’ll need it.

Of course, in a less complicated world, we’d have looked upon Ramírez as one of the greatest right-handed hitters who ever lived … and (no doubt) a first-ballot Hall of Famer. But we aren’t living (or voting) in that world, and that’s Manny’s fault, as a two-time PED offender.

Ryan Braun also came up short in this election. Make that way short. He got just 3.5 percent of the vote. It was his first year on this ballot. It will also be his last. He, too, was a two-time PED offender, even if he did get one of those offenses tossed off his official record on a technicality. In this election, his final bill for those offenses came due.

So now that those two are about to disappear from this ballot forever, we’re down to one last PED legend standing. That would be noted Netflix-er and Fox pundit Álex Rodríguez. He barely outpolled Ramírez by a handful of votes, with 40 percent.

I’m intentionally not including Pettitte here, for the same reason I laid out earlier in this column. Whatever his PED connection was, it happened in the era before testing and punishment. And we honestly have no idea who did what in that era.

So if Pettitte ever gets elected, he wouldn’t be any different from a handful of other players the writers elected from those pre-testing days, despite questions about what they did or didn’t do. And let’s remind you again that the longtime Yankees left-hander has just two years remaining on the ballot.

OK, that brings us back to A-Rod. This was his fifth time on this ballot. He has five years of this purgatory remaining. So here’s my question:

Once his five years are up, are we about to return to an age when Hall of Fame voting is about baseball again, as opposed to all those years where that tiresome PED sideshow was always lurking?

I think we are. Phew!

We’ve been dealing with this now for the last 20 elections. Ever since Mark McGwire arrived on the ballot in 2007, there has been somebody around with PED black clouds, so this could never totally be a baseball debate. But I think we can finally see those clouds lifting.

Robinson Canó is eligible to join this ballot in two years. But he’s also a two-time offender who served 242 games worth of suspensions for his two positive tests.

He’d have a fantastic Hall of Fame case if it weren’t for, well, you know. So he’s never going to have to choose which cap to wear on his plaque. The only question is whether he gets enough votes in Year 1 to survive to Year 2.

For that to happen — or for Rodríguez to pick up momentum — their only hope would seem to be a massive swell of support from all the new voters entering the Hall of Fame voting booths. But let’s look at how Manny and A-Rod fared with new voters over the past few years. That should tell us all we need to know.

YEARMANNYA-ROD

2026

13 of 36

13 of 36

2025

10 of 20

11 of 20

2024

4 of 17

6 of 17

(Source: Hall of Fame Tracker)

What about that says that any player — no matter how great — is going to get elected by the writers (or an era committee) if there’s a PED suspension (or two) on his permanent record? That’s 73 first-time voters, over the past three years, who have had a chance to prove that new voters think differently than old voters on this matter. Only 27 of those 73 thought Ramírez was worth a vote, and A-Rod didn’t fare much better.

So I’m not going to pretend we’ve handled the PED crowd perfectly over these last two decades, because that was impossible. For all the fans who screamed at us, Keep the cheaters out, I wish you’d sent us a list of every player who ever took something or other. Never got that list. Had to play a hopeless guessing game. That didn’t go well.

But don’t overlook the good news. We may not have been great at this — but at least we’re almost done!