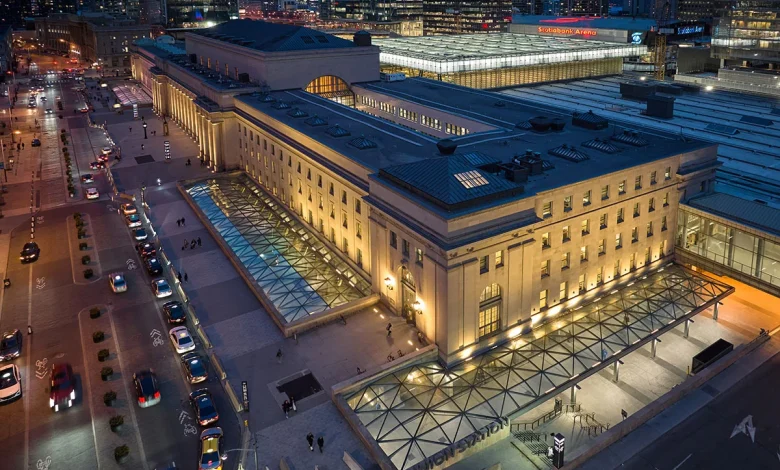

Toronto the Great: Union Station Revitalization, Toronto, Ontario

The 14-year-long, 270,000-square-foot expansion of Union Station involved carving out new passenger and retail areas under the rail tracks and below the Beaux-Arts head house.

PROJECT Union Station Revitalization, Toronto, Ontario

ARCHITECT NORR Architects & Engineers Limited

HERITAGE ARCHITECT EVOQ Architecture

TEXT Pamela Young

PHOTOS doublespace photography

For many years, the Great Hall of Toronto’s Union Station was arguably the grandest hamburger stand on the planet. Constructed over a 14-year period and completed in 1927, Union Station (original architects: John M. Lyle, Ross & Macdonald, and Hugh G. Jones) epitomizes Beaux Arts refinement and monumentality. But think back, those of you long acquainted with the Great Hall’s barrel-vaulted vastness, to what you saw when you stood near its centre, facing south: straight ahead, a heroic Corinthian-columned portal, leading down to the VIA Rail concourse, flanked by imposing archways leading. . . nowhere. Well, not nowhere, exactly. The east one cycled through various mundane service and retail uses, and the west one dead-ended as a Harvey’s burger joint.

The first comprehensive makeover in Union Station’s history commenced in 2007 and is now at last nearing completion. It has eradicated many peculiarities that this designated National Historic Site accumulated over time. (R.I.P., Great Hall Harvey’s; hello, new concourse-level access.) Encompassing restoration, renovation, a massive dig-down expansion, and the financial collapse of the first two of its three contractors, the project has transformed what was originally a railway station accommodating 40,000 passengers annually into a facility aligned with its present status as Canada’s busiest multi-modal transportation hub. Sixty-five million passengers flow through Union Station each year—and it is now positioned to handle double that volume in years to come.

Scenarios for this long-overdue overhaul began percolating in 2000, when ownership of the station building (a.k.a. head house) and below-grade GO and VIA concourses passed from a rail consortium to the City of Toronto. (Metrolinx, which operates the GO regional commuter transit network, owns the train shed’s tracks-level space.) In addition to federal, provincial, and municipal funding, the project required a private revenue stream. Possibilities ranging from a professional sports venue to station-topping condo towers were floated. And then a 2006 feasibility study led by NORR and heritage architecture specialists EVOQ got traction with a logistically complex but compellingly unobtrusive proposal: carve out additional space under the tracks and below part of the head house. The ensuing 270,000-square-foot expansion has nearly doubled the size of the previous Bay Street GO concourse and added a similarly sized York Street GO concourse, along with 160,000 square feet containing stores and a cosmopolitan profusion of restaurant and food-court space.

The project involved extensive excavation, including below the active rail tracks. This work was completed while maintaining full operations of the tracks above. Photo by NORR Architects and Engineers

NORR’s Silvio Baldassarra, Executive Architect in charge of the Union Station Revitalization from 2006 until 2024, when he stepped down as NORR Chair Emeritus, says that an operational transit facility’s successful renovation is contingent upon enabling the public to flow through in a safe, unruffled way, even as “sparks are flying and parts of the building are missing” on the other side of construction partitions. Below Union Station’s train shed, 185 columns were jacked up ever so slightly, had their loads transferred onto bedrock-supported micro-piles, and were then cut away. To prevent track sag, this bravura engineering feat’s execution required remarkable precision. “We had a commitment to Metrolinx that the movement of the tracks would be less than six millimetres, and in fact it was less than three millimetres,” says NORR Structural Engineering Principal Hassan Saffarini. Amazingly, eleven of Union Station’s twelve tracks remained operational at all times throughout construction.

Other structural challenges abounded, ranging from seismic upgrades to the head house to a desire to space columns in the main new double-height retail zone wider apart than in the pre-existing column grid above them. (There’s an Easter egg on the new lower levels for the structurally observant: if you’re amid rectangular columns, you’re under the head house, and if the columns are round, you’re below the tracks.)

The complete restoration of the historic Great Hall included the production of specialty glass to reinstate the west archway window and the glass bridges beyond it. Three quarries were reopened to source stone matching the original limestone and marble materials palette.

The revitalization addresses many issues relating to configuration and usage changes, including some quirks that actually predated the original facility’s completion. The head house was constructed not only before the tracks, but before consensus on whether tracks would be accessed from above or below. Those blocked-off Great Hall side vaults would have accommodated the from-above route not chosen. The revitalization has converted them to concourse access points.

Commuter train concourse space was renewed and greatly expanded, and shopping and food concourses were added on a new, lower level.

Union Station’s narrow track platforms were configured to handle relatively modest numbers of long-distance rail travellers arriving at relatively infrequent intervals. Today, rush-hour commuters swarm through the station every few minutes. The large, new GO concourses provide multiple new access points to the platforms and are essentially holding areas that mitigate track-level overcrowding: commuters don’t know which platform their train is departing from until electronic signage and announcements provide this information a few minutes prior to departure.

The station’s newly opened-up east end visually connects the old architecture to the new. A key move the design team made just east of the Great Hall was to truncate a light well and alter the floor height, bringing the main floor of the east wing level with the Great Hall’s floor. The base of the shortened light well is now a laylight over this main floor, and a new aperture cut through the floor, directly under the laylight, provides views down to the new retail space. Limestone wall panels extend the Great Hall’s materiality into the renovated space, while details such as the opening’s glass-panelled steel railing are minimalist-contemporary. “Part of our strategy was to use noble materials to connect to the original building in a modern, complementary way,” says David Clusiau, NORR North America’s Vice President of Design.

A service trench that previously encircled the building was reworked as skylight-topped pedestrian areas.Previously, commuters moving between Union Station’s subway stop and the main building needed to cross an open-air passage with a staircase, presenting accessibility challenges. Photographer unknown

Improved accessibility, a priority throughout, is dramatically apparent in the ‘moat’, which extends east and west of the Great Hall along Front Street and around the corners. This was originally open-air, below-grade space for baggage, taxis and post-office functions; the east moat subsequently became the primary connector between Toronto’s subway system and the train station. Anyone transferring between the two had to negotiate a flight of stairs. By relocating the sewer main that had necessitated the grade change, the revitalization has smoothed this transition to a gentle ramp. It has also capped the moat with a steel-ribbed glass canopy that combines protection from inclement weather with worm’s-eye glimpses of skyscrapers and the CN Tower. While evoking the rational elegance of historic train shed roofs, this covering keeps a low profile: a parapet screens it at street level, minimizing its visual impact on the original building. And while its springing points align with Union Station’s fenestration, the canopy stops short of the heritage façade, to avoid impacting it structurally. Meanwhile, the decision to pedestrianize the moat meant that loading had to happen elsewhere. Infrastructure that most visitors to Union Station will never see now enables delivery vehicles approaching from the lakeshore to thread their way through the basements of Scotia Square Arena and other buildings and arrive at a new, below-the-tracks loading area on the station’s south side.

(c)DOUBLESPACE

EVOQ Principal Dima Cook has led the revitalization’s heritage scope since the 2006 feasibility study. “The challenge was really understanding the building well enough to be able to propose changes that actually worked with it,” she says. The restoration was, for starters, a colossal cleaning job. Exposure to coal-powered steam locomotives, diesel trains, cigarettes, and combustion engines had left the building inside and out in a condition Cook describes as “filthy.” There was also considerable exterior spalling, but fortunately the Great Hall’s exquisitely engineered vault of thin, coffered Guastavino tile remained structurally sound.

The restoration unobtrusively upgraded building systems. In the VIA concourse, recreating the original configuration of between-columns panels to create a central dropped-ceiling band made it possible to install sprinklers and electrical trays, without height loss across the entire ceiling. Original cast-iron storefront frames recreated for this concourse seamlessly integrate supply and return ventilation grills.

The logistics of sourcing stone to match the limestone and many types of marble used throughout the original building is an engrossing story in its own right, but a brief excerpt will have to suffice here. A grey-green shade of Missisquoi marble used extensively in the Front Street Promenade—the station’s original and now-restored retail zone—comprises only a narrow band within the multi-hued slabs once mined from a Quebec quarry that had been closed. By selecting a dark-grey shade within the same slabs for a high volume of finishes in the expansion, the design team persuaded the owners that it would make economic sense to reopen the quarry.

An area that previously served as a back-of-house vehicle parking area, just east of the York Street underpass and below the tracks above, was recaptured as part of an expanded pedestrian circulation network for Union Station. The new public north-south route adjoins York Street, and is a significant improvement from the narrow sidewalk that preceded it. On the roadway side, the masonry wall between a series of structural arches was removed and infilled with glass, while on the station side, a new façade is punctuated by multiple access points up to the tracks and into the concourse.

The pandemic that hit thirteen years into Union Station’s lengthy revitalization has changed work patterns in ways that have slowed projections for travel volume to double to 130 million passengers annually by 2030. (A newer projection is 95 million passengers annually by 2036.) But an irreplaceable heritage building now has the capacity for growth that will enable it to serve its city for a long time to come. “The revitalization has been transformative to Union Station,” says Scott Barrett, Director of Property Management and Key Assets at City of Toronto. “Not only has it improved capacity and overall experience, but it has also helped to transform the station into a destination in its own right.”

NORR’s David Clusiau speaks of early 20th-century Toronto landmarks such as Union Station, the R.C. Harris Water Treatment Plant and the Prince Edward Viaduct as reminders of a time when infrastructure, in addition to solving problems, ennobled the fabric of the city. “On this project, I think we’ve been able to leverage the value of the existing building and continue that in the spaces we’ve been able to create,” he says. In a city that now routinely constructs high-rises in behind hollowed-out heritage facades and calls this evisceration “preservation,” the dig-down at Union Station is something very special indeed.

Pamela Young is a Toronto-based writer and communications manager.

Floor plans show the limited main floor areas previously open to the public (bottom right) compared to the public areas that are part of the renewed Union Station.

CLIENT City of Toronto | ARCHITECT TEAM NORR—Silvio Baldassarra (FRAIC), David Barrington, Hadi Khouzam (MRAIC), Hassan Saffarini (Hon RAIC), David Clusiau (FRAIC), Andrew Majewski, Sara Saleh, Kenneth Brooks, Chul Kim, Paul Noskiewicz, Nick Bogut. EVOQ Architecture— Dima Cook (MRAIC), Catherine Fanous, Georges Drolet (FRAIC), Julia Gersovitz (FRAIC), Giovanni (John) Diodati (FRAIC) | STRUCTURAL/MECHANICAL/ELECTRICAL NORR Architects & Engineers Limited | INTERIORS NORR Architects & Engineers Limited | CONTRACTOR (PHASE 1) Carillion Canada | CONTRACTOR (PHASE 2) Bondfield Construction | CONTRACTOR (PHASE 3) EllisDon | CIVIL Giffels Associates Limited / IBI Group (now Arcadis) | CODE Leber Rubes Inc. | TRAFFIC AND LOADING B.A. Consulting Group Ltd. | BAGGAGE HANDLING ARP Engineers | VERTICAL TRANSPORTATION H.H. Angus and Associates, Limited | WASTE MANAGEMENT Kaizen, Food Service Planning & Design Inc.| HERITAGE LIGHTING DESIGN Gottesman Associates | CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT/STAGING Ingersoll & Associates Inc.| COST Hanscomb Limited | SIGNAGE Entro Communications | SURVEY AND MEASURED DRAWINGS J.D. Barnes Limited | ENVIRONMENTAL Pinchin Environmental Ltd. | MASONRY CONSERVATOR Trevor Gillingwater | METAL CONSERVATOR Edmund Bowkett | PLASTER CONSERVATOR Rod Stewart | AREA 86,9573 m2 | BUDGET $824 M | COMPLETION December 2023