The Gruffalo returns: How Axel Scheffler created everyone’s favourite monster

Twenty-five short years ago the Gruffalo lumbered into the beloved bestiary that includes the Lion and the Unicorn, the Jabberwock and the Wild Things. Overnight, this fearsome, yet strangely lovable beast became a millennial classic to rival the kids’ book phenomenon that was Harry Potter.

A generation of bedtime storytelling has since thrilled to Julia Donaldson’s tale of impending dread in a deep, dark wood. Now, finally, there’s a new Gruffalo story, Gruffalo Granny, announced today (6 February), in advance of a world-wide book launch in September.

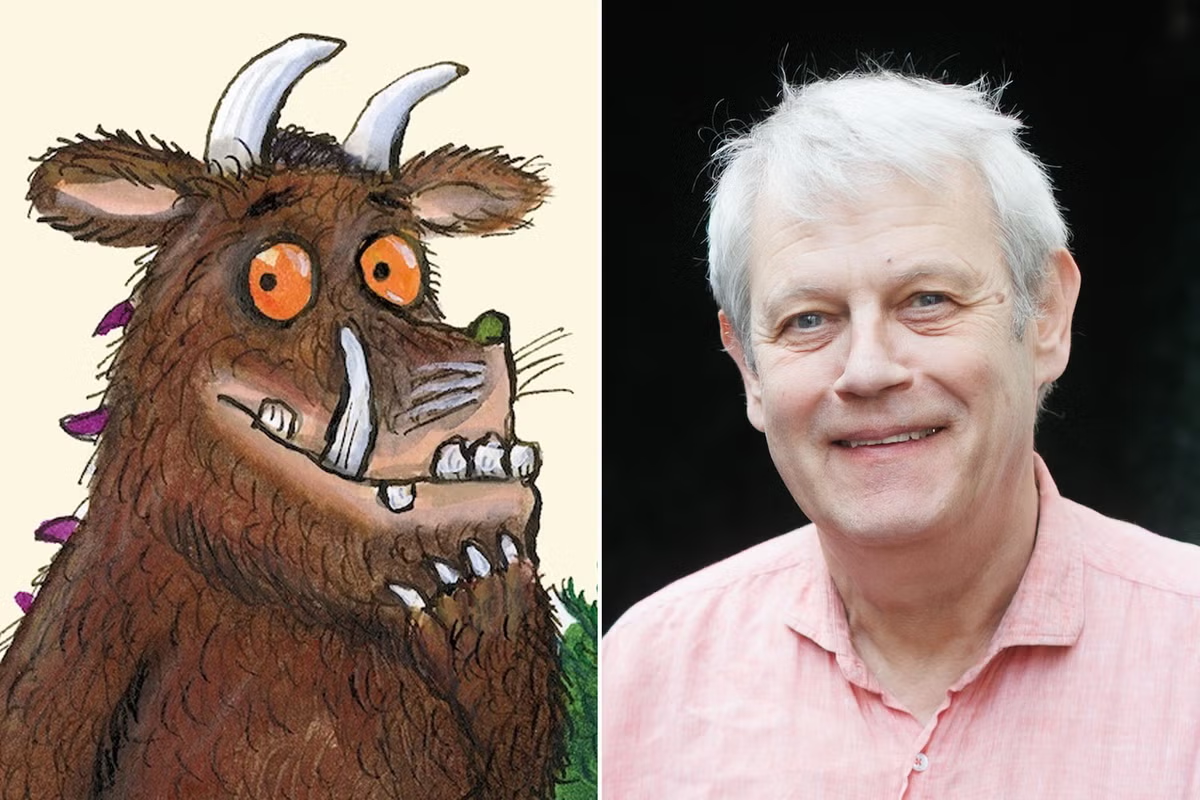

I went to meet Axel Scheffler, the artist whose prime as an illustrator has been devoted to his image of this iconic creature, and found myself sitting in off-season sunshine with this slightly rumpled, ex-pat German while he sketched the kids’ book character he refers to, with obvious affection, as “my monster.” If there’s a subtle frisson of pride in Scheffler’s voice that’s because this treasured monster is not just any old ogre, but a multi-million pound superstar.

The Gruffalo, with his “terrible tusks and terrible claws”, first clumped into our childrens’ consciousness in the spring of 1999. A generation later, Donaldson’s tale of a little brown mouse who “took a stroll” in a fairytale forest, outwitted some fearsome predators, to triumph over adversity with plucky cunning, has become part of every child’s imaginative landscape, a contemporary classic inspired by a Chinese fable, “The Fox that Borrows the Terror of a Tiger”. I suspect that quite a few parents will also confess to a mild obsession with this fabulous creature.

Scheffler’s not saying – he’s an easy-going, quite reticent man – but it’s a fair guess that this story has sold many hundreds of thousands of copies. The Gruffalo is now as much part of our children’s inner landscape as Hansel & Gretel. Here, the artist pauses mid-sketch to observe that such success would have astonished his father, who worried that his dreamy son would never amount to much. Scheffler pere was a teenage soldier who’d manned an ack-ack searchlight in Berlin during the final days of the Third Reich. Through the post-war “Wirtschaftswunder” years, in which the country redeemed itself after the horrors of World War, he had been the managing director of a German food factory.

open image in gallery

‘The Gruffalo’ was published in 1999 (Macmillan Children’s Books)

Axel Scheffler is a baby-boomer, born in Hamburg in 1957, who grew up in a broken society re-making itself through hard work. His childhood reading, such as it was, involved Mickey Mouse and a Danish classic about “Petzi”, a naughty little bear. The Scheffler family was devoted to restoring the status quo, and were middle-of-the road in another way too: they were the kind of Anglophile Germans who loved to take English holidays. One idyllic visit to Devon during the magical summer of Seventy-Six became a turning-point for Axel; he has a

lifelong love for the British landscape. As a quite solitary boy, he would lose himself in drawing. In 1982, having done social work instead of military service in the Bundeswehr, the young conscientious objector packed his paints, brushes, easel and pencils to set off for the Bath Academy of Art in Corsham. It was here, ambushed by his vocation, that he discovered the simple ambition of becoming an illustrator.

The idea that this might be a “proper job” was slow to dawn, but he was happy in England. His early years, Scheffler admits, with a wry smile, did not involve too much starving in garrets. From a flat in Streatham, the young artist shopped his work to the magazines that still commissioned illustrations (Time Out; The Listener), and also to a rising generation of childrens’ book publishers. Walker Books gave him some work; then Faber commissioned a book cover and a set of illustrations for Helen Cresswell’s The Pie-Makers, followed by some more artwork for The Bottle-Rabbit (now a collector’s item). By the early 1990s, Scheffler was collaborating with an up-and-coming childrens’ book writer named Julia Donaldson, to make illustrations for her latest poem, “A Squash and A Squeeze”, a comic rhyme about farm animals.

open image in gallery

Dream team: Author Julia Donaldson and illustrator Alex Scheffler (Urszula Soltys)

Scheffler did not know it, but his new co-author was also in the throes of completing a childrens’ poem about a little brown mouse who outwits a monster. Better still, she was coming into her own – in the words of one critic – as “one of the best ears for prosody since WH Auden”. Donaldson, indeed, had already submitted her “Gruffalo” to a publisher who – for reasons shrouded in shame and mystery – let this quirky poem gather dust during the mid-90s. Eventually, in frustration, she’d recovered her neglected manuscript, dusted it off, and sent it to Scheffler. Was it, she wondered, something he might consider illustrating?

That was a no-brainer, of course. Donaldson’s seductive mix of Chinese folk-tale with nursery rhyme is touched with genius. “I remember very well reading it,” says Scheffler with Germanic understatement. As luck would have it, he was about to have dinner with a childrens’ book publisher, who, recognising the timeless brilliance of the poem, did not hesitate to make an immediate offer. Things moved quickly; the die was cast. All at once it became Scheffler’s responsibility to put flesh and bones on Donaldson’s sublime creation.

Inevitably, there was some trial-and-error in the birth pangs of the terrible “gruffalo”. Initially, Donaldson pictured her fearsome beast in a rougher guise. Later, she confessed to Scheffler a penchant for the art of Gustave Dore, the classic French 19th century book illustrator. Next, their publisher worried that Scheffler’s first sketches might alarm a juvenile audience. The Gruffalo’s eyes were too small; there was a problem with his teeth. Er…. In a word, “could you make him less scary?”

There is something in the Gruffalo books that reflects our personal history

Scheffler was unfazed; these were typical publisher-illustrator exchanges. In the end, “my monster”, as he calls him, became that classic, the monster who’s not a monster. Of course he’s afflicted with “purple prickles” and has “a poisonous wart at the end of his nose”, but underneath, he’s a big softy. For all his “terrible teeth” (surely, he’s English?), he’ll scarper at the first hint of trouble.

The Gruffalo has the ageless charm of the perfect tale. Still, there’s no doubt that Scheffler’s visualisation is integral to its success. The artist is careful to repeat his admiration for Donaldson’s “genius” but, like Carroll’s John Tenniel, Milne’s EH Shepherd and Dahl’s Quentin Blake, he knows it’s his illustrations that supercharged her words towards posterity, with drawings that contribute to the making of a fictional universe.

A true classic, a poem about the power of a good narrative, The Gruffalo achieves a bewitching marriage of wonder and dread. The cool terror of the words becomes softened by the innocence, clarity and warmth of Scheffler’s art. “I see myself as a humorous illustrator,” he says, conceding that his art-work subtly complements Donaldson’s style. There is, he confides, “something in the Gruffalo books that reflects our personal history.”

open image in gallery

(Liam Jackson)

Is it, I wonder, too fanciful to find him tapping into a rich vein of mittel-European fairy-tale imagery? Scheffler’s natural reticence resists this line of inquiry. “Let’s leave that to the psychoanalysts,” he replies with a laugh. Now, as he returns to drawing – for the umpteenth time – a portrait of the Gruffalo, he reflects on his brush with fame, and remarks “I am lucky not to be recognised.”

Home is Richmond Hill, where he lives with his partner Clementine, and their teenage daughter, surrounded by the tools of his trade – paints, brushes and a fistful of pencils. It’s not just sweetness and light. In a momentary flash of Teutonic steel, the shy anglophile shakes his head over Brexit. “A very sad day. Such a terrible mistake. What were you thinking?” Politics aside, he’s perfectly content. “There’s nothing else I want to do. I have no dream project.” Sometimes, possibly tongue-in-cheek, he wishes he could paint like Caspar David Freidrich, the supreme German Romantic landscape painter, but otherwise he’s happy.

open image in gallery

(Axel Scheffler)

Gruffalo Granny will be launched in September 2026, but that’s not really so new, whatever the publishers say. “The Gruffalo hasn’t changed after all these years,” he says, embellishing his drawing. Like Prospero, he seems to cherish his power over an imaginary kingdom.

It’s already been a generation. “Julia always said, No sequel for twenty-five years.” As our conversation comes to a close, Scheffler’s sketch is almost complete. Does he converse with the Gruffalo in his head? Scheffler seems puzzled. “Why would he talk to me? He’s a monster….” A beat. “My monster.”