US plans 500kW lunar nuclear reactor in bold 2030 space power push

NASA could place a powerful 500-kilowatt-electric (kWe) nuclear reactor on the Moon by the end of 2030, as part of a bold, high-stakes move aimed at securing long-term US energy dominance in space.

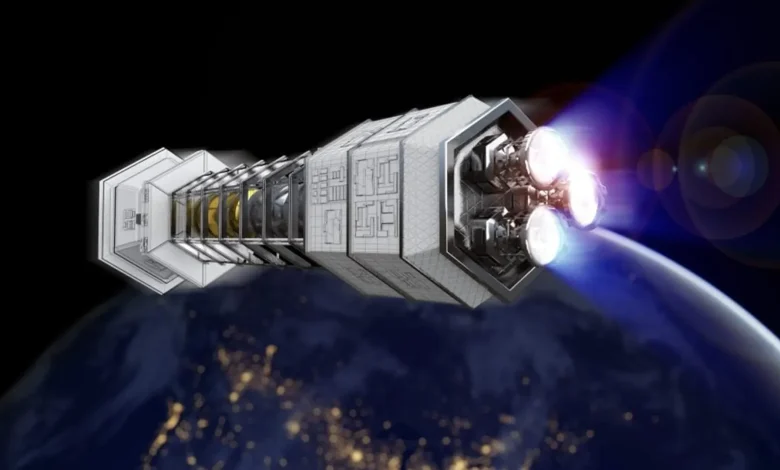

The system, developed under the space agency’s Fission Surface Power Initiative, would represent a significant leap beyond the radioisotope generators that have powered missions like Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, and the Mars rovers for decades.

According to NASA, in comparison to smaller systems, a 500-kWe reactor could continuously power lunar habitats, industrial equipment, communication arrays and even resource extraction operations.

“It might sound like science fiction, but it’s not,” Sebastian Corbisiero, the Space Reactor Initiative national technical director, explained. “It is very realistic and can significantly boost what humans can do in space because fission reactors provide a step increase in the amount of available power.”

Powering the Moon

Although no fission reactors are currently operating in space, the agency issued a directive on fission surface power. It reportedly intends to place a reactor on the Moon by fiscal year 2030. The strategy is outlined in a new report funded by the Idaho National Laboratory (INL).

Titled “Weighing the Future: Strategic Options for US Space Nuclear Leadership,” the document outlines three approaches. The most ambitious, described as “Go Big or Go Home,” calls for a 100–500 kWe reactor program led by NASA or the Department of War, with support from the Department of Energy.

The reactor would be designed to run for 10 years without maintenance in space.

Credit: Idaho National Laboratory

The report argues that scaling up to 100-500 kilowatt-electric (kWe) systems is essential if the nation aims to stay ahead in space nuclear power. Meanwhile, a second option, named “Chessmaster’s Gambit,” proposes two smaller sub-100 kWe systems developed through public-private partnerships.

One project, led by NASA, would reportedly build a reactor for lunar orbit or the Moon’s surface. The other, led by the Department of Defense, would develop an in-space system.

Ultimately, a third, more cautious alternatives involves developing a small, under one kWe, radioisotope power system, in order to establish regulatory frameworks and technical groundwork before scaling.

Space’s nuclear future

Unlike terrestrial advanced reactors, space-bound fission systems must operate under entirely different conditions. “The big differences are mass, temperature and component endurance,” Corbisiero emphasized.

At the same time, everything sent into space has to launch on a rocket, so the reactor must be as light as possible while still strong and durable. According to Corbisiero, that makes weight a top priority.

What’s more, water, commonly used in Earth-based reactors, may not be practical due to the heavy pressure vessels required. NASA is evaluating high-temperature alternative cooling systems to reduce mass while maximizing power density.

The reactors must also endure extreme temperature swings, radiation exposure, and micrometeoroid risks, all without routine servicing. INL is expected to serve as the technical hub for reactor testing and fuel qualification.

With specialized staff and state-of-the-art facilities like the Transient Reactor Test Facility, INL is equipped to conduct critical testing of nuclear propulsion reactor fuels and host new reactor technologies on-site.

“We’re potentially on the cusp of a major step forward regarding nuclear power for space applications,” Corbisiero concluded in a press release. “To be a part of an effort like this – that is as exciting as it gets. That’s something you tell your grandkids.”