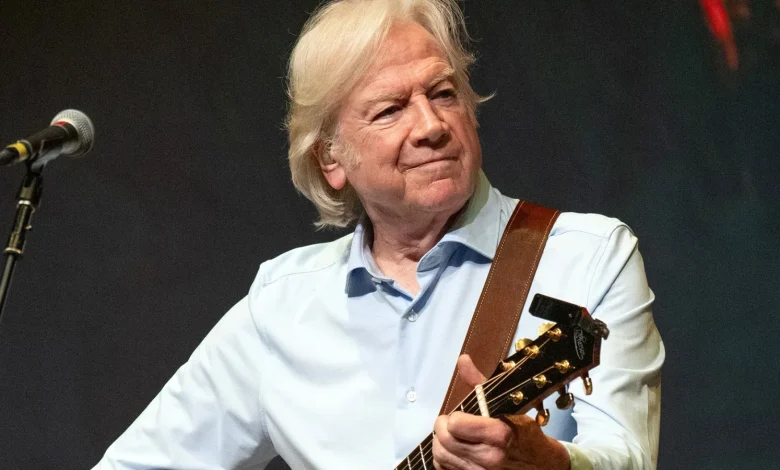

Justin Hayward on Outliving All his Moody Blues Bandmates

When the Moody Blues entered the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in April 2018, co-lead singer Justin Hayward accepted the honor alongside drummer Graeme Edge, keyboardist Mike Pinder, bassist-singer John Lodge, and original frontman Denny Laine. “We’re just a bunch of British guys,” a beaming Hayward told the crowd at Cleveland Public Hall. “But, of course, to us and to all British musicians, this is the home of our heroes. It’s all the people that have come along and changed the world.”

In the years since that long-overdue celebration, the world of the Moody Blues has been rocked by a devastating, improbably high number of deaths in a short period of time that leaves Hayward as the only living member inducted that night. (Lodge died in October, and we lost Pinder in 2024, Laine in 2023, and Edge in 2021).

It’s a reality that becomes even grimmer when you factor in the death of original bassist Clint Warwick in 2004, flutist-singer Ray Thomas weeks before the 2018 induction, and mid-Sixties bassist Rod Clark this past March. The only living musician other than Hayward with a credible claim to being a genuine Moody is 1980s keyboardist Patrick Moraz, but a jury of his peers disagreed when he sued the band for wrongful termination in 1992, and the Hall of Fame affirmed that decision when they opted to not induct him.

The Moody Blues have been completely inactive since a series of West Coast concerts in late 2018, but Lodge and Hayward kept the music alive throughout the past seven years by playing it on their own separate solo tours across North America and Europe. But after Lodge’s sudden death in October, Hayward is left flying the Moodies flag all on his own.

We caught up with Hayward via Zoom at his home in a “small village near the French side of the Italian border” to chat about the long history of the Moody Blues, his status as the last survivor, and what he plans to do going forward to keep the legacy alive.

We last spoke in 2017 when the news broke about the Moodies getting into the Hall of Fame. How have you processed everything that’s happened since then?

It’s curious how many people have said that to me. And … I’m not wrestling with that. It’s not like family. I don’t have the same feelings as when I lost my brother, who died very young. I don’t have those same feelings.

Editor’s picks

It seems that I’m expected to go through different processes, but I only have good and happy memories, really. I can’t say that we were close or that we saw each other regularly, or anything like that. The Moodies is a family, in its way, because it’ll always be linked because of business.

I want to go through some of the history here. When you joined in 1966, they were essentially a one-hit wonder band.

That’s rather cruel.

I’m not putting them down. I love “Go Now.” I love that first record. It’s just they had only the one hit and were fading when you came in.

Well, I think if the group had wanted to continue the R&B style, they’d probably picked the wrong guy in me. And I wasn’t being much help to them along those lines. It didn’t really suit me.

I came to the Moody Blues really thinking of myself as a songwriter. I was very happy to get the call from Mike [Pinder] that day. He called me because he heard my songs. He didn’t know what I looked like, except that my mother had given me a big buildup, because he called my mother first. And then my mother found me at some music shop. I think even at that first meeting with Mike Pinder we had discussed wanting to do our own songs, because he was writing, and we were the only two people in the band who were writing songs at that time. And so that was his way of trying to make the band move forward.

Related Content

The Beatles were going through an incredible creative evolution at the time. In what ways did they inspire you creatively?

It’s hard to explain the impact of the Beatles, now, to people who weren’t there in the 1960s. But every move they made, everything they said, everything they recorded, everywhere they went, influenced everybody in that quite small London scene. Of course, it impacted the whole world, everything they did, but they were the kings of that particular small world in London at that that time. It was a group of a few hundred people, and we were very much in the middle of that. They were the leaders in everything that they did. And you could not help be aware of the changes that they were making.

I remember walking down the street after hearing “Love Me Do” on the radio for the first time, and knowing that the world was going to be different. Now, how did I know that? But there was something in just one record, that it was like “Hallelujah!” And then I remember there was a man, I think his name was Steve Race, who came on the BBC a week or so after this. And did that usual thing about, “Oh, they’ll never last. It’s a one-hit wonder,” kind of thing. And everybody was like, “What? How dare you say things like that?” We took things completely personally about the Beatles.

It’s sort fascinating to think that as they’re recording Sgt. Pepper, you guys are making Days of Future Passed at basically the same exact time.

Yes. In fact, Mike was visiting the studio in Abbey Road, because it wasn’t far away from Broadhurst Gardens. But our circumstances were very different. We had nothing. But the stars aligned to help us make Days of Future Passed.

How did the Mellotron change the way you guys created music?

Well, it made my songs work. Before that, the song that we most liked was a song called “Fly Me High,” and that really centered around Mike’s piano. And as I said, we were kind of struggling. I think our price had dropped to less than 50 pounds a night.

We came back from some gigs in a cabaret, up in the north of England. We were doing the kind of rhythm and blues set, and some guy came in the dressing room afterwards. We thought he was going to say the usual kind of complimentary sort of things, but he didn’t. He said, “I’ve got to tell you that you’re the worst group I’ve ever seen in my life, in this venue. And somebody’s got to tell you.”

I think Ray started crying, and then I did. And when we were on our way back to London in the van, nobody spoke. And Graeme had a place in the back of the van that he’d made on some equipment. And when we got to about Scotch Corner, which is halfway back to London, I heard this little voice coming, from Graeme in the back of the van saying, “He’s right, that bloke, we’re crap. We’ve got to do something.”

And really, Mike had that sort of light-bulb moment. “I know where there’s a Mellotron.” He worked for Mellotronics, and he and I went up to the Dunlop Social Club in Birmingham, fishing out of the corner of this social club, and we bought it for about 20 or 25 pounds.

I’ve heard a lot of stories from bands like Genesis about how impossible it was to bring that thing on tour.

It was extremely awkward, and it broke down at one of our first gigs in America in ’68, which was the Fillmore East in New York. John Mayall was on the bill, and I think he was secretly sniggering with glee that our Mellotron had broken down. But we took all of the transformers and amplifier parts out of it, and duplicated the orchestral sounds. Because they were really invented as a sound-effects instrument, with trains going through tunnels, and cockerels in the morning, and that kind of stuff. And so we duplicated all of the orchestral sounds, so they were kind of instantly double-tracked, and that was the sound of our Mellotron.

Did band politics get tricky once you became successful?

If there were tensions in the group, it’s because we became two groups. We were a recording band that was quiet, with the acoustic guitars at the front, and the Mellotron with that big spread. And then we became a touring band that had to get louder and louder and louder. And some of us didn’t mind that. Me and John and Graeme didn’t really mind that, but Mike didn’t like the loud version. He liked the studio version.

How did you feel about the prog scene that rose up in the early 1970s, groups like Yes, Jethro Tull, and Genesis, that all clearly took some elements of what you guys were doing?

I wasn’t paying attention to them. I think my record collection was elsewhere. And I think the moment of our first tour of America just sent me personally off in a different direction. There were a couple of gigs we did with a group called It’s a Beautiful Day, who I just thought were sensational, and very kind of graceful in their performance. And we did a couple of gigs with another group called Love, and then Jefferson Airplane, of course. So I think that we went off on a tangent, an American kind of tangent, with our music and our musical influences. I don’t think we were that conscious of what was happening in the U.K.

You’ve been called “proto-prog,” but you were never doing the 30-minute songs or long keyboard solos or anything. You had a very different sound.

Well, for me personally, I was just trying to write a really great pop song. And I think that was incorporated into the themes, that most of the time were led by Graeme. And of course, the spoken word gave us that reputation, as well.

The band had incredible momentum in 1972 with Seventh Sojourn and “I’m Just a Singer (In a Rock and Roll Band).” You were never more popular. Why did you decide in that moment to take off five years?

Well, nothing was said that couldn’t be unsaid. That was nice. But we got to the end of a long world tour, and we just didn’t make any plans. I suppose it goes back to that thing, “Which group do you want to be in? Do you want to be the recording band that’s sounding more and more kind of American, or do you want to be the touring band that’s louder and louder and louder?”

My amps had gone from an AC30 to a 50-watt Marshall to a 100-watt to a 200-watt, to a 200-watt with a slave [amplifier]. And I think Mike particularly was feeling uncomfortable. So it was just nobody signed up for any more gigs, there was nothing in the book, suddenly.

In the years the Moodies were gone, a lot of bands moved into football stadiums. Do you ever think about the alternate path they might have taken if they stayed together and continued with the momentum from Seventh Sojourn?

Well, that’s interesting, isn’t it? No, I don’t think so. I don’t have any regrets about that, or yearning that it would have been different in any way. I was very happy in what I was doing, and the path that it led me, and it gave me an opportunity to do a couple of solo albums, to be part of an album called The War of the Worlds that has, to this day, given me great success as a solo artist around the world.

I was the one, I think, at that time who was a bit lost. Because everybody else said, “Right, we’re not doing anything. I’m going to plan this.” But I found myself in Los Angeles at the end of that tour, we’d finished in Japan. And I thought, “Well, I don’t know what to do now. So I’ll just go to Los Angeles, because that’s where things seem to be happening, and I’ll wait for the phone to ring.” And eventually it did.

During the time the Moodies weren’t around, the punk movement broke out in New York and London. Groups like the Sex Pistols saw groups like the Moody Blues as the enemy. How did you feel about what was happening there?

I don’t think they thought of us as the enemy. It’s curious. I always think about those records now, like the Clash and the Sex Pistols … I just thought Sid [Vicious] was just absolutely brilliant. But you could see it was a car crash waiting to happen. And, when you look back now, how well-recorded some of those things were. They don’t sound scruffy or un-together at all. They’re well-thought-out and nicely recorded. So if you’re rebelling against that part of the music business, it didn’t work for them. But no, maybe the fact that we were apart for five years kind of helped us, because at the end of that we just seemed to be able to breeze straight back in, and we fit right in somehow.

Mike left the band after Octave in 1978. How did his absence change things?

Well, then we became four people looking for a keyboard player, and then it was Graeme who got connected with Patrick Moraz. And I think he really turned us on. His contribution was really large, from that time on, ’79 through ’til the sort of mid-’80s.

And then, personally, I think he just lost interest where he wanted to do other things. He wanted to really make it on his own. And not only had Mike left, but there was a kind of rupture with Tony Clark as well, who was the record producer. His personal life had changed so much that he didn’t identify with being one of a particular group like the rest of us, somehow.

We deliberately put ourselves in a situation where we would meet people, record producers. And Pip Williams was great, Alan Tarney, and then Tony Visconti a couple of years later, changed the whole world for us.

How was it for Ray and Graeme in an era of drum machines and synthesizers, and less flute? Was it tough for them to find their way into these albums?

You really have thought about these things, more than I have. Well, that’s interesting. Now, Graeme was totally on board with it. Of course, the first thing I did was rush out and buy myself a sort of time clock, a click clock I used to call it. And the first thing we did with that was a song called “The Voice” from Long Distance Voyager. And so, I got it all set because I had a nice home recording system, and then I would take my click clock and my stuff into the studio, and do it to a time code.

Now, Graeme loved that. Graeme was totally on board with that, which was wonderful. There was none of that, “Oh, you’ve got to feel it, because the time needs to move.” There’s none of that. He was totally in with it. And I think he got a LinnDrum himself, that he was messing around with. So that was fine.

Ray was a different kind of, because his writing was very sort of tongue in cheek, and looking at life in a particular lighthearted way. And so I think as a writer, he always… He was never at a loss in the group. Neither of them were. Both of them were big characters within the group.

In 1986, 20 years after you joined, the band suddenly has this giant hit and you’re all over MTV and Top 40 radio. I’m sure it was surreal to suddenly have this whole new audience that maybe didn’t even know your older work.

Exactly. You’re right. A lot of people did start with “Wildest Dreams,” really. And fortunately, I think we still looked good. I was coming up to the end of my thirties. We could carry it off.

What was fortunate as well is that a couple of us had got really kind of skint. We had seen nothing, really, of the financial rewards of those earlier years. We were never celebrities. We were never on TV, or anything like that. We never commanded a huge price for our appearances.

But in the mid-’80s, we were starting to be offered so many live gigs that I think we just went with it, and that really did change our lives. The summer tours that we did, the double headers, say with the Beach Boys or Chicago…. I loved all that time. The wonderful sheds in America, that were such great places to play. And still are, I hope.

If you look back at that time, Paul McCartney and Mick Jagger couldn’t get a hit. Bob Dylan was struggling. So many giants of the ’60s were flailing, and you guys have this enormous smash.

Well, Tony Visconti knew how to make a record.

A few years later, you found yourself battling Patrick Moraz in a courtroom, and the entire thing was broadcast on Court TV. That had to be a really strange moment.

Yeah, well, what can I say? I had a house in West London, and I went out one day, and there was somebody outside the door with a great big bunch of papers. They just had to touch me with them. I said, “Excuse me?” “You’re being served with this writ,” or whatever it was. It fell at my feet. And I thought, “What the fuck? Oh, well, these things happen.” Well, there wasn’t a moment from the first day in the Moody Blues where we were without some kind of litigation, over some amplifiers or something going on.

And so I ignored it, very stupidly, until we appeared onstage in California for the first time after that. And it happened to me again. The sheriff’s department came up to me, in the center of the group, and served me with these papers. And then, of course, I had to take it seriously. And God forbid that anybody should be served with something in California, have to sit in a courtroom in California.

We had, of course, had all the representation we could possibly muster. But we had to listen to the case against us that was…. I have to say the words “ambulance chaser” kind of representation that was against us. But it was actually brilliant, all the mud that was swung at us. I was sitting there when it was the other guys, not so much when it was me, and kind of thinking, “That’s pretty clever. Because in that, there is a grain of truth, and 90 percent bullshit. But there is something in it.”

Was the Nineties a difficult time? After 1991 or so, a song like “Wildest Dreams” simply isn’t possible anymore. Radio and MTV basically only cared about young acts.

Well, a very fortunate thing happened to us, because a promoter in Colorado suggested that we might want to do a concert with the Colorado Symphony, at a place called Red Rocks. So PBS got on board with that. And I put a lot of work into that concert, into making it right. And that kicked off a whole decade of doing that.

In most towns in America, there is a subsidized orchestra, a proper professional quality, brilliant orchestra. And our agent realized, “Hey, there’s one of these in every town. You could do 58 different orchestras.” And so, once we’d got the parts, that’s exactly what we did. And we built a reputation through the ’90s of appearing with local orchestras. Which was a great time for us.

Why did Ray leave the band in 2002?

The honest answer is that I don’t actually know. His health wasn’t good, and he was having to sort of drag himself up onstage. It was really tough for him, getting out there every night. And I think me, John, and Graeme were, particularly with three dicks like us, full of energy like, “Come on, yeah, let’s do it. We’re great, girls, oh, it’s fantastic.” Ray was kind of struggling. He had to have a chair onstage. And I could see it coming

The last thing I wanted for him was that he should be unhappy. It came home to me one day when I called him about a tour. It was close to Christmas, like about this time of year, and we were talking about early the next year to do some stuff. And we were just having a general chat. And then I said about these dates that were coming in, and he said, “Well, I don’t think I’m going to do it.” And so I said, “Well, never say never, eh? You know, Ray?” And he came out with a great line. He said, “You can say what you fucking want, but I’m not coming.” I thought, “Right, I got it. Understand, Ray. I understand.”

Did you stay close to him after he left? Did you talk to him much?

A little bit, but if you leave a group, you don’t tend to stay friends…. No, “friends” is not the right word. You don’t tend to stay in each other’s company, do you?

It’s tough to play drums every night when you get older. How did Graeme manage in his final years of touring?

Always happy. The group meant everything to Graeme. His love for the group…. Well, I didn’t know anything else like that. He wouldn’t hear anything against it. Whatever we did, his advice and opinion was always for the best, always only wanting the best for the group. And I think that where we did need my click clock and my LinnDrum, he fiddled around for a couple of years trying to get it with him onstage, and him pressing buttons and stuff like that.

In the end, I think we all agreed: “Maybe we’ll get another guy who is just a clock player. That the only thing that matters is the time.” I think, actually I would have to say that in any recording, time is the most important thing. It helps the groove, and everything.

He was all on board with finding somebody to go to be with him onstage, a second drummer, to absolutely keep that time. And he could be free to do his thing, because the sound of his drums were the best-sounding drums I’ve ever heard. I often would go with him up from Charing Cross Road to drum stores, to try and choose things for him. And the sound of his drums was beautiful, and he had a light, light touch.

What was it like seeing Mike again at the Hall of Fame? Did you guys reconnect?

Yes, absolutely. I’d seen Mike a couple of times over the years. In fact, he’d come to see me in one of my solo shows. Married to a beautiful girl. I think that the issue was actually between Graeme and Mike. That was to do with Graeme’s devotion to the band, and Mike wanting to do other things outside of the band, or not to be there. Not to make it a 24 hour a day job. I’m not sure whether they reconciled it, actually.

When you guys got into the Hall of Fame, did you know the touring days were coming to an end?

That’s a really good question. I don’t know. Were there any tours planned in 2019? And then of course, the world did end, really, during Covid, didn’t it? For me personally, I have to say when Graeme Edge passed, I think it really did change things, for me.

There was no farewell tour. Were you offered anything like that?

No, I don’t think there was. It just seemed, for me, time. It was time. And I’m very lucky to have my own things, and always an outlet for my songs, and fortunate as a vocalist that I’ve been asked to do things as well.

Did John agree it was time, or did he want to keep the band going?

I don’t know. I’m not sure that we saw each other. After that 2018 tour, I’m not sure whether we even saw each other after that, because of Covid. And then, we came out of that all a little bit different.

The last show was in La Jolla in 2018. Did you walk offstage thinking to yourself that it was over?

This is something that, it’s hard to describe, really. But right from the beginning, right from the start, there was never any plan or any strategy. That never existed. So there was never meetings about, “What shall we do?” Or, “How should we do this?” Or something like that. Things just happened to us. We either did them, or we didn’t.

So many people love Days of Future Passed, and I hope it survives over the years. I think maybe the time has gone when people listen to things like that, but I don’t know. But it’s always assumed that there must have been a plan and a strategy, and a sort of blueprint for that and how it was going to happen. And there wasn’t anything. It was just one afternoon, somebody saying something, and then the next afternoon you’d do it. And then it was happening. And that’s the way it was with the Moody Blues. If you say that’s the last gig, at La Jolla, there was no meeting about, “What should we do,” or anything like that.

You didn’t speak to John in the last seven years of his life?

I don’t think so, no. But then, I didn’t speak to Graeme either, much. I maybe had one call with him, or something like that. What we had in common was the group. That was what we were good at. That was our relationship. It wasn’t a group of friends.

People always have this fantasy that people in bands are best friends. It’s rarely true.

I think with certain groups, Bono and Edge, it probably is true.

In recent years, people saw you touring solo and John touring solo, and presumed maybe there was some sort of falling out.

No. No, not at all. Actually, certainly not. No plan or strategy about falling out, either.

He died rather suddenly. The news must have been shocking.

Every one of the guys was, yes. Yes, the first one I think would have been Ray. That was shocking, and saddening. And then with Graeme, It’s like, “Well, that’s the end of that chapter.”

Denny Laine died too. Did you have a chance to talk with him at the Hall of Fame?

I did. And I think I was probably the only one to speak with Denny, because there were some bad feelings from when I joined, really. I knew him, not intimately, but I knew him just around, in the years before the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. And I was so glad that he was there. He was part of it. And I also think that Clint Warwick should have been given a mention, too.

At this point, it’s really only you and Patrick Moraz left.

Oh. I didn’t know Patrick was still around.

Have you spoken to him at all since the lawsuit?

No. No. I have my own life. I got my own stuff, my own family, and my own music. And I’m very lucky to have that. And I’m thankful every day to be a Moody Blue for the very best years of my life. And in such a great band. We didn’t have to go and socialize all the time, but when we were onstage, or when we were in the studio, we were a great band. And the band that I wanted to be in.

Are you playing solo shows next year?

Yes, yes, yes. I’m offered a lot of work, and I find myself saying yes to it. I’ve got great musicians around me, and I can call on great musicians, and I’m very lucky. I have a fantastic crew, devoted, who love this music.

Do you feel any sense of obligation to keep the music alive since it’s down to just you?

Well, I’ve got nothing else. So I’ve got my own music, of course. I’m lucky to have had solo things, all throughout the Moodys’ life. And the only thing I try to be conscious of, I try in my touring life to be true to the way…. Because I’m doing my own songs, true to the way I wrote those songs, and to the way I made those demos. True to the sort of click clock that I used to use, and yes, the feeling of them. That’s why my acoustic guitars are mostly to the fore, and my guitar tech, Josh. I’ve been teaching him how to play exactly like me, so that he can accompany me.

Do you ever think about any sort of farewell tour at some point?

A farewell Justin tour?

Sure.

I don’t know. For me, it’s about the voice. People say to me, “How do you look after your voice?” And I always want to say, “Well, my voice looks after me, really.” So as long as that’s there. I practice quite a bit, I had a practice today. I’ve got a friend who’s got a big room at the back of his house, and I was there today. Because I shout.

Are you working on a new record?

I’ve got some projects going in the studio right now, yeah. And I’m sure they’ll come to fruition. And there’s so many things from my early days, from my mother who loved show tunes, and who played the piano, and was a very kind of theatrical person. She was a teacher, as were both of my parents, and both of them academics in their way. But some of the songs from those days, I’m still interested in exploring myself, and putting my own personality into them. But I know what people want from me, and I want to share that. I want to put myself into songs and to write more.

Trending Stories

To wrap up here, I know you weren’t close with the other guys, but you must really miss them on a musical level and the camaraderie you all shared.

There was a time when it was wonderful, and then there was a time when it wasn’t so. No, I don’t miss anything. I don’t miss anything, and I don’t have any regrets. I’m just thankful that we had that time together. Yeah, I’m thankful for those times. I don’t miss anything, and I didn’t want to kind of recreate it with people who weren’t there.

Right. Playing as the Moody Blues with other people would feel wrong.

It wouldn’t seem right to me. And I don’t have any need to.