Opinion: At least one part of the U.S. campaign against Venezuela makes sense: taking on the ‘dark fleet’

Open this photo in gallery:

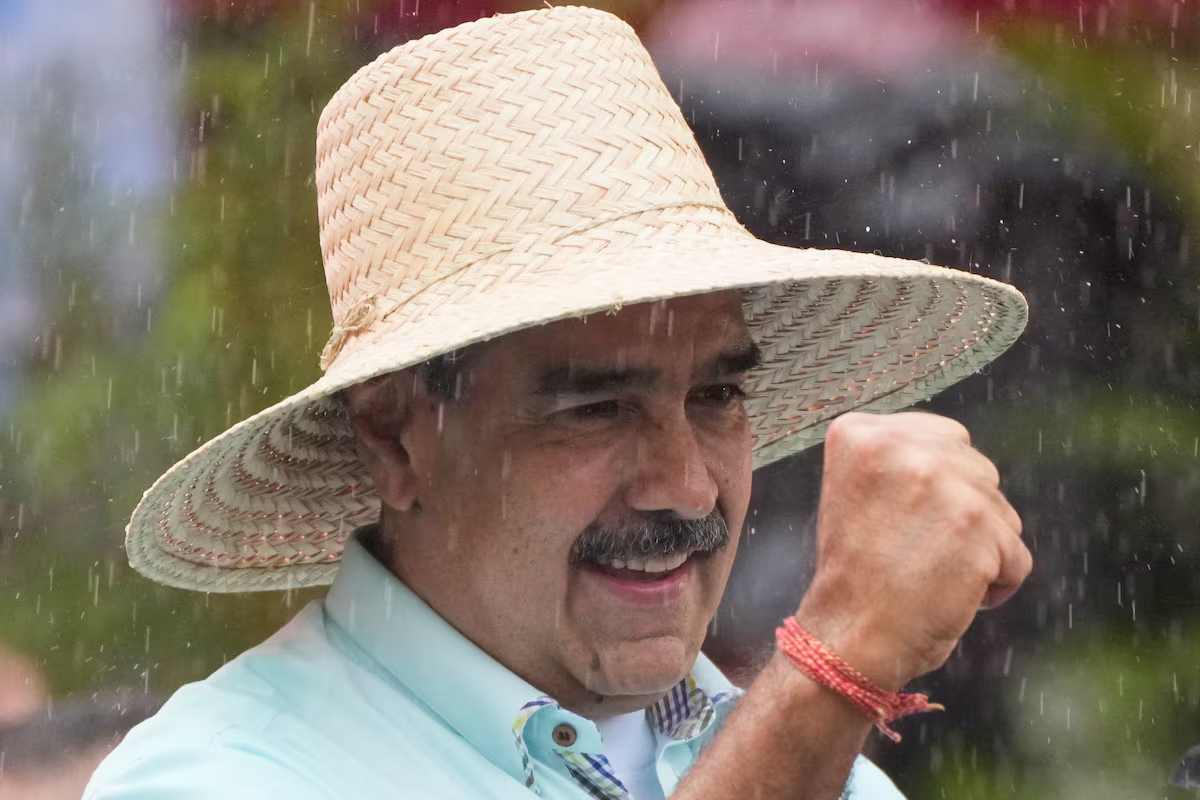

Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro during a rally in Caracas earlier this month.Ariana Cubillos/The Associated Press

Michael Byers teaches global politics and international law at the University of British Columbia.

Amid a months-long conflict where the United States has been enacting air strikes against small boats off the coast of Venezuela – which many experts have deemed illegal – the Donald Trump administration last week tried a less violent, more legally acceptable way to press Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro to step down. On Dec. 11, U.S. forces seized a tanker carrying oil from Venezuela to China, and while this was decried by Caracas as piracy, the action was consistent with international law: The ship was pretending to be registered in Guyana, and, by flying a “false flag,” had rendered itself stateless.

On Tuesday, Mr. Trump upped the ante by declaring a blockade on all “sanctioned” tankers from Venezuela. To be supportable, that approach would have to be limited to the newly emerged “dark fleet” of more than 1,000 tankers. But the first approach – seizing an individual tanker flying a false flag – creates an opportunity for other countries to insist that this fleet poses intolerable safety, environmental and economic risks, and that international law allows enforcement action against all such vessels.

Doug Saunders: Venezuelans need regime change. But Trump’s help will only harm

Dark ships either fly a false flag or are registered in a “flag-of-convenience state” that lacks the capacity or will to enforce International Maritime Organization (IMO) rules, such as Gabon, Guinea, Honduras, Djibouti, Palau and landlocked Eswatini. Ships will also “flag-hop,” changing their state of registration frequently.

Dark ships will either deactivate the automatic identification system that all vessels are required to use, or “spoof” the signal the system sends to satellites to show a false and distant location.

Most dark-fleet ships also violate another IMO rule by not carrying insurance. They are operated through layers of shell companies that conceal their ultimate ownership.

Safety risks arise because the ships are old, poorly maintained, and captained by people who cannot find work with legitimate shipping companies. Turning off or spoofing the AIS only increases the risk of a collision and a resulting oil spill. Such a spill could be devastating for any nearby coastal state, and not just in environmental terms. Consider the costs imposed on a coastal state by an oil spill from an uninsured vessel, as opposed to an insured one.

Opinion: The ghost of the Monroe Doctrine haunts the U.S.’s buildup in Venezuela – and Canada must oppose it

Dark fleet techniques have been employed for decades to evade sanctions on North Korea, Iran and Venezuela. But the recent and rapid growth of the fleet, which could comprise as much as 20 per cent of the world’s tankers, can be attributed to the sanctions imposed on Russia after its 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Those sanctions included a US$60-per-barrel price cap on all Russian oil exports by sea, with legitimate shipping and insurance companies risking punishment by Western states if involved in sales above that price. China and India were prepared to pay more than that, however, so less reputable companies seized the opportunity to transport Russian oil to them.

To provide the destination country with plausible deniability, dark ships often transfer their cargo to another ship while still at sea. Such transfers make the oil more difficult to track, and increase the risk of a spill.

Russia, China and India are powerful countries, so the West has taken little action against the dark fleet. Western governments have justified this inaction on the basis that all properly flagged vessels, regardless of their behaviour, have always been entitled to “freedom of the seas.”

Opinion: Canada risks complicity in the high-seas killings committed by the U.S.

But international law is always evolving. Consider how the international legal system expanded to outer space with the launch of the first satellite in 1957. Or how, in 1998, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda ruled that sexual violence during armed conflict constitutes a war crime.

Today, the dark fleet is imposing risks on every coastal state. It can therefore be argued that a flag-of-convenience state that registers a vessel but makes no effort to enforce IMO rules against it should lose the right to shield that vessel from enforcement measures by other states. Global concern about dark ships might also cause Russia, China and India to show restraint if more of them were seized. It would help, too, if proceeds from selling the ships and cargo went to the oil-industry-funded International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds, which provide compensation for pollution from tankers.

Canada and other countries should follow the lead of the United States on the specific issue of dark ships. Any flag-of-convenience state that registers ships but does not enforce international rules against them needs to know that, from now on, dark ships will face real consequences. As for Mr. Trump’s blockade, the next few days should tell us whether it is a restrained and thus legally appropriate action, or the next step in a military campaign of regime change.