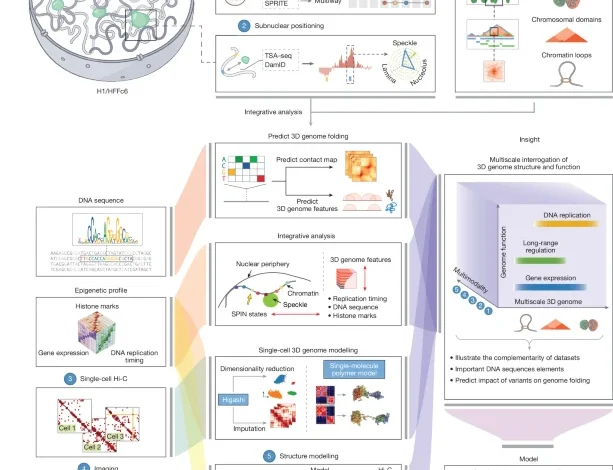

An integrated view of the structure and function of the human 4D nucleome

GAM methods and data processing

Preparation of cryosections

H1 cells were fixed and processed for cryosectioning as described previously140. In brief, H1 cells were grown to 70% confluency, the medium was removed and cells were fixed in 4% and 8% paraformaldehyde in 250 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.6; 10 min and 2 h, respectively), gently scrapped and softly pelleted, before embedding (>2 h) in saturated 2.1 M sucrose in PBS and frozen in liquid nitrogen on copper sample holders. Frozen samples were stored in liquid nitrogen. Ultrathin cryosections were cut using a Leica ultracryomicrotome (UltraCut EM UC7, Leica Microsystems) at approximately 220 nm thickness, captured on sucrose-PBS drops and transferred to 4 µm PEN steel frame slide for laser microdissection (Leica Microsystems, 11600289). Sucrose embedding medium was removed by washing with 0.2-μm-filtered molecular biology grade PBS (3 × 5 min each) and filtered ultrapure water (5 min). For laser microdissection, cryosections on PEN membranes were washed, permeabilized and incubated (2 h, room temperature) in blocking solution (1% BSA (w/v), 5% FBS (w/v, Gibco 10270), 0.05% Triton X-100 (v/v) in PBS). After incubation (overnight, 4 °C) with primary anti-pan-histone (1:50) antibody (Merck, MAB3422) in blocking solution, the cryosections were washed three to five times for 30 min in 0.025% Triton X-100 in PBS (v/v) and immunolabelled (1 h, room temperature) with secondary antibodies in blocking solution, followed by three (15 min) washes in PBS.

Isolation of NPs

Nuclear staining was visualized using a Leica laser microdissection microscope (Leica Microsystems, LMD7000) using a ×63 dry objective. Individual nuclear profiles (NPs) were laser microdissected from the PEN membrane, and collected into PCR adhesive caps (AdhesiveStrip 8C opaque; Carl Zeiss Microscopy 415190-9161-000). GAM data were collected in multiplexGAM mode, where three NPs are collected into each adhesive cap. The presence of NPs in each lid was confirmed with a ×5 objective using a 420–480 nm emission filter. Control lids not containing NPs (water controls) were included for each dataset collection to keep track of contamination and noise amplification of whole genome amplification and library reactions. Collected NPs were kept at −20 °C until whole-genome amplification.

WGA

Whole genome amplification (WGA) was performed as described previously141 with minor modifications. In brief, DNA was extracted from NPs at 60 °C in the lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1.4 mM EDTA, 560 mM guanidinium-HCl, 3.5% Tween-20, 0.35% Triton X-100) containing 0.75 U ml−1 Qiagen protease (Qiagen, 19155). After 24 h of DNA extraction, the protease was heat-inactivated at 75 °C for 30 min and the extracted DNA was amplified by two rounds of PCR. First, quasi-linear amplification was performed with random hexamer GAT-7N primers with an adaptor sequence. The lysis buffer containing the extracted genomic DNA was mixed with 2× DeepVent mix buffer (2× Thermo polymerase buffer (10×), 400 µm dNTPs, 4 mM MgSO4 in ultrapure DNase-free water), 0.5 µM GAT-7N primers (5′-GTGAGTGATGGTTGAGGTAGTGTGGAGNNNNNNN) and 2 U µl−1 DeepVent (exo-) DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, M0259L) and incubated for 11 cycles in the BioRad thermocycler. The second exponential PCR amplification was performed in presence of 1x DeepVent mix, 10 mM dNTPs, 0.4 µM GAM-COM primers (5′-GTGAGTGATGGTTGAGGTAGTGTGGAG) and 2 U µl−1 DeepVent (exo-) DNA polymerase in the programmable thermal cycler for 26 cycles. WGA was performed in 96-well plates using Microlab STARLine liquid handling workstation (Hamilton).

Preparation of GAM libraries for high-throughput sequencing

After WGA, the samples were purified using the SPRI magnetic beads (1.7× ratio of beads per sample volume). The DNA concentration of each purified sample was measured using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay kit (Invitrogen, P7589). Sequencing libraries were then made using the in-house tagmentation-based protocol. After library preparation, the DNA concentration for each sample was measured using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay, and equal amounts of DNA from each sample was pooled together. The final pool of libraries was analysed using DNA High Sensitivity on-chip electrophoresis on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and sequenced on Illumina NextSeq 500 machine.

GAM data sequence alignment

Sequenced reads from each GAM library were mapped to the human genome assembly GRCh38 (December 2013, hg38) with bowtie2 (v.2.3.4.3) using the default settings. All non-uniquely mapped reads, reads with mapping quality

GAM data window calling and sample quality control

Positive genomic windows present within ultrathin nuclear slices were identified for each GAM library as previously described141. In brief, the genome was split into equal-sized windows, and the number of nucleotides sequenced in each bin was calculated for each GAM sample with bedtools. Next, we determined the percentage of orphan windows (that is, positive windows that were flanked by two adjacent negative windows) for every percentile of the nucleotide coverage distribution. The number of nucleotides that corresponds to the percentile with the lowest percentage of orphan windows in each sample was used as an optimal coverage threshold for window identification in each sample. Windows were called positive if the number of nucleotides sequenced in each bin was greater than the determined optimal threshold.

The sample quality was assessed by the percentage of orphan windows in each sample, total genomic coverage in percent of positive windows, the number of uniquely mapped reads to the mouse genome and the correlations from cross-well contamination for every sample. Each sample was considered to be of good quality if it had ≤40% orphan windows, ≤60% of total genome coverage, >50,000 uniquely mapped reads and a cross-well contamination score determined per collection plate of

GAM data curation

To exclude genomic windows which were under- or oversampled in the GAM collection, we computed a GAM-specific parameter, the window detection efficiency (WDF)31 as previously described142. To detect genomic bins with outlying detection frequency, a smoothing algorithm was applied to the WDF values per chromosome in stretches of eleven equally sized genomic windows. Next, normalized delta (ND) was calculated for each window, according to: ND = (raw_Signal − smoothed_Signal)/smoothed Signal. If the ND was larger than a fold change of 5, the window was removed from the final dataset. Next, the four adjacent windows (2 upstream and 2 downstream) were also removed, to ensure good quality of sampling in the final GAM data used for further analyses.

Genomic bins with an average mappability score below 0.2 were also removed. Genome mappability for the hg38 human genome assembly was computed using GEM-Tools suite143 setting read length to 75 nucleotides. The mean mappability score was computed for each genomic bin with bigWigAverageOverBed utility from Encode.

GAM data normalization

GAM contact matrices for all pairs of windows genome-wide were generated as previously described to produce pairwise co-segregation maps and pointwise mutual information (NPMI) maps that consider window detectability141. For visualization of the contact matrices, scale bars are adjusted in each genomic region displayed to a range between 0 and the 99th percentile of NPMI values in the region.

GAM insulation scores

The insulation scores were calculated from NPMI-normalized pairwise chromatin contact matrices, as previously described25 with minor modifications adjusted for GAM input data by keeping both positive and negative values in the matrix141.

Identification of compartments A and B in GAM data

Compartments were calculated using co-segregation matrices, as previously described142. In brief, each chromosome was represented as a matrix of observed interactions O(i,j) between locus i and locus j. The expected interactions E(i,j) matrix was calculated, where each pair of genomic windows is the mean number of contacts with the same distance between i and j. A matrix of observed over expected values O/E(i,j) was produced by dividing O by E. A correlation matrix C(i,j) was calculated between column i and column j of the O/E matrix. PCA was performed for the first three components on matrix C before extracting the component with the highest correlation to GC content. Loci with eigenvector values with the same sign were designated as A compartments, whereas those with the opposite sign were identified as B compartments. For chromosomes 3 and 22, we manually picked PC1 and PC2, respectively, as the PC that correlated most with GC content did not display a typical AB compartmentalization pattern and good correlation with transcription levels.

Data processing for Hi-C, Micro-C, ChIA-PET, PLAC-seq and SPRITE

Cooler files for Hi-C, Micro-C, ChIA-PET, PLAC-seq and SPRITE were downloaded from the DCIC Data Portal (links to all data are provided in the Supplementary Information). Contact matrices were normalized using the iterative correction procedure from a previous study144. Interaction heat maps were created using Python. The colour map is ‘YlOrRd’ and the colour scales are created taking the 10th and 90th percentile of the interaction frequencies of individual datasets. No additional processing was applied to GAM data.

HiCRep correlations

HiCRep is used to calculate distance-corrected correlations of the multiple methods145. Correlation is calculated in two steps. First, interaction maps are stratified by genomic distances and the correlation coefficients are calculated for each distance separately. Second, the reproducibility is determined by a novel stratum-adjusted correlation coefficient statistic by aggregating stratum-specific correlation coefficients using a weighted average. Chromosome-specific correlation was performed for pairwise protocols and the correlations across those chromosomes were then averaged. Averaged pairwise correlations of chromosomes 1–22 and X were used to calculate the HiCRep correlations between Hi-C, Micro-C, ChIA-PET, PLAC-seq and SPRITE datasets; averaged correlations of chromosomes 1–22 were used to calculate HiCRep correlations between GAM and all other datasets. We used 50-kb binned interaction matrices to calculate HiCRep correlations.

Compartment analysis

Compartments were assessed for Hi-C, Micro-C, ChIA-PET, PLAC-seq and SPRITE using eigenvector decomposition on observed-over-expected contact maps at 100-kb resolution using the cooltools package derived scripts146. An eigenvector that has the strongest correlation with gene density is selected, then A and B compartments were assigned based on the gene density profiles such that A compartment has high gene density and B compartment has low gene density profile. A and B compartment assignments of GAM were provided by the data producers.

Spearman correlation was used to correlate the eigenvectors of different experiments performed with various protocols and cell states. Saddle plots were generated as follows49: the interaction matrix of an experiment was sorted based on the eigenvector values from lowest to highest (B to A). Sorted maps were then normalized for their expected interaction frequencies; the top left corner of the interaction matrix represents the strongest B–B interactions, the bottom right represents the strongest A–A interactions, the top right and bottom left are B–A and A–B, respectively. To quantify saddle plots, we took the strongest 20% of BB and strongest 20% of AA interactions and normalized them by the sum of AB and BA (top(AA)/(AB + BA) and top(BB)/(BA + AB)). Saddle quantifications were used to create the scatter plots. The parameters that were used for the saddle plot are as follows: –strength, –vmin 0.5, –vmax 2, –regions hg38_chromsizes.bed, –qrange 0.02 0.98, –contact-type cis.

Preferential interactions

Bigwig or bedgraph files for lamin B1 DamID-seq, TSA–seq and Repli-seq were downloaded from the DCIC Data Portal (a full table of links is provided in the Supplementary Information).

Heat maps that integrate 3D methods with genome activity plots were generated as follows: first, the data were binned into 50-kb bins for aforementioned assays and sorted from the highest to the lowest value. Additional filters were applied for early/late replication ratio. For early/late replication timing data, bins with no values and the bins with value of 0 were removed, and the outlier bins that have values >98th quantile were also removed and the minimum value for the first bin was kept as 0.

Second, the interaction matrices (Hi-C, Micro-C, ChIA-PET, PLAC-seq, SPRITE and GAM) are sorted based on the 1D tracks generated from the aforementioned assays from the highest to the lowest.

Next, sorted matrices were then normalized for their expected interaction frequencies; the upper left corner of the interaction matrix represents the strongest signal for non-preferential interactions, lower right represents strongest preferential interactions. To quantify these plots we took the strongest 20% of the preferential interactions. Saddle plot parameters are listed below for this quantifications: –strength, –vmin 0.5, –vmax 2, –regions hg38_chromsizes.bed, –qrange 0.02 0.98, –range min(Sorted 1D data) max(Sorted 1D data) –contact-type cis. For GAM, –strength, –vmin 0.1, –vmax 0.4, –regions hg38_chromsizes.bed, –qrange 0.02 0.98, –range min(Sorted 1D data) max(Sorted 1D data) –contact-type cis.

Insulation score

For Hi-C, Micro-C, ChIA-PET, PLAC-seq and SPRITE, we calculated diamond insulation scores using cooltools (https://github.com/open2c/cooltools/blob/master/cooltools/cli/insulation.py) as implemented previously25. We defined the insulation and boundary strengths of each 25-kb bin by detecting the local minima of 25-kb binned data with a 100-kb window size. We used cooltools’s diamond-insulation function with the following parameters: –ignore-diags 2. Insulation scores of GAM were provided by data producers. We separated weak and strong log2-transformed insulation scores using the mean insulation score of all protocols (that is, weak insulation scores

Identification of chromatin loops in different platforms

We used different strategies for detecting chromatin loops in different platforms.

For Hi-C and Micro-C, we combined results from HiCCUPS23 and Peakachu63. To identify chromatin loops using HiCCUPS, we ran cooltools dots (v.0.5.1)146 at 5-kb and 10-kb resolutions with the default parameters. Peakachu is a machine-learning based framework that learns contact patterns of pre-defined chromatin loops from a genome-wide contact map and applies trained models to predict loops on other maps generated by the same/similar experimental protocol. Here, we first trained Peakachu models on GM12878 Hi-C data at 2-kb, 5-kb and 10-kb resolutions, using a high-confidence loop set detected by at least two platforms among Hi-C, CTCF ChIA-PET, Pol2 ChIA-PET, CTCF HiChIP, H3K27ac HiChIP, SMC1A HiChIP, H3K4me3 PLAC-seq and TrAC-loop. These models were then used to predict chromatin loops on Hi-C and Micro-C maps of H1 and HFFc6 cell lines at corresponding resolutions. The probability cut-offs were manually adjusted to balance sensitivity and specificity based on visual inspection.

For ChIA-PET, we combined loop predictions from ChiaSig147 and Peakachu. For each ChIA-PET dataset, we conducted multiple runs of ChiaSig with varying parameter settings, specifically adjusting the -M, -C and -c parameters while keeping other parameters constant (-m 8000 -S 4 -s 6 -A 0.01 -a 0.1 -n 1000). The -M value was selected from 1000000, 2000000 and 4000000, while both the -C and -c values were set to either 2 or 3. Only chromatin loops consistently identified across all parameter settings were retained, while others were discarded. As ChiaSig heavily relies on 1D peak annotation for loop detection, chromatin interactions outside peak regions are not identified as loops. To capture loops with similar contact patterns to those detected by ChiaSig but outside peak regions, we again used Peakachu to learn the patterns. For each ChIA-PET dataset, we trained 23 Peakachu models using interactions detected by ChiaSig, with each model trained on data from different combinations of 22 chromosomes. During prediction, loops on each chromosome were predicted using the model trained on the other 22 chromosomes. The probability cut-offs were determined to ensure that Peakachu-predicted loops covered 90% of ChiaSig-detected interactions. Training and prediction were conducted separately at 2-kb and 5-kb resolutions, and the final loop predictions for each ChIA-PET dataset were obtained by combining ChiaSig-predicted interactions and Peakachu predictions.

For PLAC-seq, we combined outputs from MAPS148 and a pipeline similar to that used for ChIA-PET. For MAPS, loops were identified at 10-kb resolution using the default parameters. For the ChiaSig-Peakachu pipeline, loop prediction was conducted at 5-kb resolution, using the same training, prediction and filtering strategies as described above for ChIA-PET.

To calculate the union of loops identified from different platforms, methods and resolutions, two chromatin loops (i, j) and (i′, j′) were considered overlapping if and only if |i − i′| i − j |, 15 kb) and |j − j′| i − j|, 15 kb). If two loops were overlapping, only the one predicted at a higher resolution (that is, with more precise coordinates) was retained.

Calculation of overlap between capture Hi-C interactions and loops from other assays

For each capture Hi-C interaction (i, j), if there exists a loop (i′, j′) identified by another assay (one of Hi-C, Micro-C, CTCF ChIA-PET, Pol2 ChIA-PET or H3K4me3 PLAC-seq) such that the Euclidean distance between (i, j) and (i′, j′) is less than min(0.3|i − j|, 80 kb), we define (i, j) as overlapping with a loop from the corresponding assay.

Consensus chromatin-state annotations for H1 and HFFc6 cells

We computed epigenomic annotations using ChromHMM (v.1.23) on 14 observed and 2 imputed ChIP–seq datasets for 8 marks (H3K36me3, H3K4me1, H3K27ac, H3K9ac, H3K3me3, H3K4me2, H3K27me3 and CTCF) in both H1 and HFFc6 cells. All the ChIP–seq datasets were obtained from the WashU Epigenome Browser (https://epigenome.wustl.edu/epimap/data/) in bigwig format, and the coordinates were transformed from hg19 to hg38 using CrossMap (v.0.5.2, http://crossmap.sourceforge.net/).

To prepare the data for ChromHMM, we divided the whole genome into 200-bp bins and calculated the average signals within each bin. For the observed data, values were binarized with a −log10[P] value cut-off of 2. For the imputed data (H3K9ac and H3K4me2 in HFFc6), we downloaded both the imputed and observed data in H1 cells for the same marks. Then, for each mark, we set the binarization cut-off for the imputed data to match the quantile in the observed data corresponding to the −log10[P] > 2 cut-off, enabling comparison with the observed data.

Finally, we ran the ChromHMM LearnModel command on the binarized data to segment both the H1 and HFFc6 genomes into 12 states. The name of each state was manually annotated based on prior knowledge about each mark. The 12_Heterochrom state was excluded from further analysis, as it did not contain signals of any marks (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

Enrichment analysis of chromatin states for chromatin loops and loop anchors

To characterize the chromatin states of loop anchors detected by specific combinations of chromatin interaction methods, we calculated fold-enrichment scores by comparing the overlap with each ChromHMM state between the observed loop anchors and 100 randomly generated control sets. Specifically, for each chromatin state, we iterated through the loop anchor list and counted the number of anchors overlapping at least one region with that state. We then randomly shuffled the anchors in the genome to generate 1,000 control sets and repeated the same procedure for each control. For each control, we kept the size distribution and the number of random regions on each chromosome the same as the observed loop anchors, and the intervals of each region did not overlap with any gaps in the hg38 reference genome. Finally, the fold-enrichment score was calculated by dividing the number of anchors with a specific chromatin state by the average number of random loci with the same state.

We used a similar method to characterize chromatin states for a specific cluster of chromatin loops. In brief, for each pair of chromatin states, we iterated through the loop list and counted the number of loops with one anchor overlapping regions marked by one chromatin state and the other anchor overlapping regions marked by the other chromatin state. Again, we generated 1,000 random control sets for chromatin loops. Each random loop set maintained the same genomic distance distribution between loop anchors and the same number of random loops on each chromosome, ensuring that the interval between the two ends of each loop did not overlap any gaps in hg38. Finally, the fold-enrichment score was calculated by dividing the number of loops between a specific pair of chromatin states by the average number of random loops between the same states.

Enrichment analysis of TFs for different loop clusters

To explore whether different loop clusters exhibit differential binding of various TFs at their anchors, we downloaded the ENCODE ChIP–seq peak files for 62 TFs in H1 cells. A fold-enrichment score was computed for each TF at loop anchors using a procedure analogous to the one described above. In brief, we first identified non-redundant loop anchors from each loop cluster in H1 cells. For each TF, we iterated through this anchor list and counted the number of anchors overlapping at least one ChIP–seq peak. Subsequently, we generated 1,000 random control sets by shuffling the loops and repeated the same procedure for each control set. The fold-enrichment score was then calculated by dividing the number of anchors containing ChIP–seq peaks by the average number of random loci containing ChIP–seq peaks for the same TF.

APA

To evaluate the overall enrichment of chromatin loop signals in contact maps, we performed APA. For a given list of chromatin loops or interactions, we extracted contact frequencies from 21 × 21 submatrices centred at the 2D coordinates of each loop. Each submatrix was normalized by dividing each value by the average contact frequency at the corresponding genomic distance. To reduce the influence of outliers, submatrices with average signal intensities above the 99th percentile or below the 1st percentile were excluded. The average signal at each position was then computed across all retained submatrices and visualized as a heat map. The APA score shown on the plot is defined as the signal intensity at the centre pixel of the aggregated heat map.

UMAP projection and clustering of chromatin loops

To construct the input feature matrix for projecting chromatin loops, we calculated the proportion of each ChromHMM state at the loop anchors in each cell line. This yielded a feature matrix Mij of size 141,365 × 22 for H1 cells and 146,140 × 22 for HFFc6 cells. Each row represents a chromatin loop, with the first 11 columns corresponding to features from one anchor and the next 11 columns corresponding to features from the other anchor.

Next, we standardized (z-score normalized) the matrix Mij. For each row in the normalized matrix, we swapped the order of the two anchors, if necessary, to ensure that the highest value appeared in the first 11 columns. The resulting matrix served as input for UMAP projection (https://github.com/lmcinnes/umap), using the parameters “n_neighbors=60, min_dist=0, n_components=2, metric=euclidean” for H1 cells, and “n_neighbors=65, min_dist=0, n_components=2, metric=euclidean” for HFFc6 cells.

For loop clustering, we first applied principal component analysis (PCA) to the swapped feature matrix, resulting in a transformed matrix of the same shape. We then constructed multiple k-nearest neighbour (k-NN) graphs using values of k ranging from 50 to 2,000 in steps of 50. The Leiden algorithm was applied to each graph for community detection, with the resolution parameter set to 0.5. Consensus clusters were derived by integrating clustering results across all k-NN graphs.

Calculation of the average contact strength for different loop clusters

To calculate the average contact strength for each loop cluster across different experimental platforms, we used distance-normalized (observed/expected) contact frequencies. Specifically, for Hi-C, Micro-C and DNA SPRITE datasets, we computed this value using interaction frequencies normalized by matrix balancing or iterative correction and eigenvector decomposition (ICE) at the 5-kb resolution. By contrast, for ChIA-PET and PLAC-seq datasets, we calculated the value using raw interaction frequencies at the same 5-kb resolution. For GAM, we used the NPMI-normalized co-segregation frequencies at the 25-kb resolution.

Annotation of enhancer regions in different cell types

To define candidate enhancer regions in each cell type, we first downloaded the total set of human cis-regulatory elements (cCREs) from the ENCODE data portal website using the following link https://screen.encodeproject.org/. We then extracted all regions marked as ELS (enhancer-like signatures) from the downloaded file. Finally, enhancer regions in each cell type were defined as a subset of these regions that overlap with ATAC–seq or DNase-seq peaks in corresponding cells, based on data availability for those cells.

Gene expression breadth analysis

To explore the gene expression profiles of a specific gene set across a diverse range of cell type or tissues, we collected RNA-seq datasets for 116 human cell types or tissues (from ENCODE; see the ‘Datasets’ table in Supplementary Note 1, section ‘Methods for relating chromatin loops to gene expression’). The TPM values were used to measure gene transcription levels. To normalize the RNA-seq data, we first applied a logarithm transformation to the original TPM values using the formula log2[TPM + 1] for each sample, and then quantile-normalized the transformed TPM values across all samples.

In each sample, genes with a normalized TPM value greater than 3 were considered expressed in the corresponding sample, and the gene expression breadth is defined as the number of samples in which a gene is expressed.

Identifying SPIN states for large-scale genome compartmentalization

In this work, we used a modified SPIN method to perform joint modelling across multiple cell types. To ensure TSA–seq and DamID scores across different cell types are comparable, we first applied a data normalization method to transform data into a Gaussian or more-Gaussian-like distribution. To do that we identified genomic bins that are spatially stable by calculating the Pearson correlation of interchromosomal Hi-C interactions for each non-overlapping 25-kb genomic bin. The bins were then ranked on the basis of the average Pearson correlation coefficient, and the top 25% were selected as spatially conserved regions. We then obtained TSA–seq or DamID scores for these bins in all cell types and standardized each data track by fitting a power-transformation function. We used the Yeo–Johnson transformation function with the default parameters from the Python scikit-learn package. Next, we modified the framework of SPIN by jointly modelling the probability across multiple cell types. The hidden Markov random field model is defined on an undirected graph \({G}^{c}=(V,{E}^{c})\) for each cell type, where in our case V represents non-overlapping 25-kb genomic bins and Ec represents the cell-type-specific edges (that is, significant Hi-C interactions) in cell type c. For each node \(i\in V,{O}_{i}^{c}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d}\) is a vector with dimension d indicating the observed TSA–seq and DamID signal of this bin in cell type c. Each node i in C also has a hidden state \({H}_{i}^{c}\) for each cell type, representing its underlying spatial environment relative to different nuclear landmarks that we want to estimate. In this work, we assume that the set of hidden states are shared across cell types. Edges \(({i}^{{c}},{j}^{{c}}\,)\in {E}^{{c}}\) in the graph are cell-type specific and there are no edges that are connecting nodes from different cell types. Therefore, the hidden state \({H}_{i}^{c}\) is only dependent on cell-type-specific observation \({O}_{i}^{c}\) and the neighbours of node \(i({N}^{c}(i)=\{j|j\in V,(i,j)\in {E}^{c}\})\) in cell type c. The overall objective is to estimate the hidden states \({H}_{i}^{c}\) for all nodes in all cell types that maximize the following joint probability as shown below:

$$P(\vec{H},\vec{O})\propto \frac{1}{Z}\prod _{c\in 1\ldots 4}(\prod _{i\in V}{P}_{V}({O}_{i}^{c}|{H}_{i}^{c})\prod _{({i}^{c},{j}^{c})\in {E}^{c}}{P}_{{E}^{c}}({H}_{i}^{c},{H}_{j}^{c}))$$

To estimate the number of SPIN states, we applied the same approaches as we used in the previous version of the SPIN method72. We used both the Elbow method based on k-means clustering and AIC/BIC scores to search for the optimal number of SPIN states. Both AIC and BIC scores decrease as the number of states increases. We found that the slope of the curve drops close to zero as the number of states exceeds 9. So, we chose 9.

Data acquisition and processing

We obtained TSA–seq, lamin B1 DamID-seq and Hi-C data for H1 and HFFc6 cells from the 4D Nucleome data portal (http://data.4dnucleome.org). The data generation and processing pipeline for TSA–seq data was described previously32,59. The data generation and processing pipeline for DamID data was described previously104. For the SPIN states inference, we used Hi-C data generated by the formaldehyde–disuccinimidyl glutarate Hi-C protocol (1% formaldehyde followed by incubation with 3 mM disuccinimidyl glutarate) using restriction enzyme DnpII42. We binned TSA–seq, lamin B1 DamID-seq and Hi-C mapped reads at 25-kb resolution. We then identified significant interactions from the normalized Hi-C data in each cell type previously described72.

Processing other epigenomic data

We downloaded or processed other epigenomic data and compared SPIN states with these datasets. For ChIP–seq datasets, we downloaded the processed P-value tracks from the ENCODE website for H1 cells and Avocado73 imputed P-value tracks from the 4D Nucleome data portal. Multi-fraction Repli-seq data were collected from a previous study106. For CUT&RUN data, we downloaded raw sequencing reads from the 4D Nucleome data portal and processed them using a similar procedure according to the standard ENCODE ChIP–seq pipeline. First, we mapped reads to the hg38 reference genome using Bowtie2 (v.2.2.9) with the default parameters. We then used MACS3 to generate P-value tracks as well as peaks for CUT&RUN data. The enrichment score of epigenomic data on SPIN states is determined by the log2-transformed ratio between the average observed signals on each SPIN states over genome-wide expectation.

SPIN states enriched caRNA sequence features

Processing of iMARGI data was performed with iMARGI-Docker77. To quantify enrichment of repetitive element (RE)-containing caRNAs with specific chromatin states, we computed an enrichment score (log2-transformed observed/expected interaction frequencies) for each RE caRNA class and SPIN state. Observed frequencies were derived from the number of iMARGI read pairs with RNA ends mapped to RE class of interest and DNA ends mapped to SPIN states. Expected frequencies are computed as the total number of iMARGI read pairs multiplied by the product of the marginal probabilities of RE class abundance (the proportion of all caRNAs mapping to each RE class, irrespective of DNA mapping locations) and SPIN state abundance (the proportion of DNA reads mapping to each SPIN state). Only interchromosomal iMARGI pairs were analysed to mitigate potential biases from nascent RNA transcripts interacting with proximal genomic regions.

Measuring nuclear RNA with iMARGI

iMARGI RNA end coverage is derived from RNA, DNA interactions represented in bedpe files generated by iMARGI docker77. The RNA end abundance bigwig file is generated by calculating the pileup reads coverage (R, coverage function) on the genome using RNA ends only in a strand-specific manner.

Methods for integrated genome structure modelling

Data preprocessing was performed as described previously81, with the exception of the parameter fmaxation = 16 for Hi-C preprocessing.

Genome representation

The genome is represented at 200-kbp resolution as described previously81,83, resulting in n = 29,838 chromatin regions, modelled as hard spheres of radius r0 = 118 nm. The HFFc6 nucleus is modelled as an ellipsoid of semiaxes (a,b,c) = (7,840, 6,480, 2,450) nm, whereas the H1 cell envelope is represented by a sphere of radius R = 5,000 nm.

We define the population of single-cell genome structures as a set of S diploid genome structures X = {X1, …, Xs}; A genome structure Xs is a set of three-dimensional vectors \({X}_{s}=\{{\vec{x}}_{{is}}:{\vec{x}}_{{is}}\in {R}^{3},{i}=\mathrm{1,2},\ldots ,N\}\) representing the centre coordinates of each chromatin domain within the structure s:, N being the total number of chromatin domains in the genome and \({\vec{x}}_{{is}}=({x}_{{is}},{y}_{{is}},{z}_{{is}})\in {R}^{3}\) indicates the coordinates of a 200,000-bp genomic region i in structure s. We use the notation I = (i,i′) to indicate the genomic region, where i and i′ represent the two alleles of genomic region I.

Data-driven simulation of genome structures

Genome structure populations were generated with IGM following procedures described previously81. The goal is to determine a population of 1,000 diploid 3D genome structures X statistically consistent with all input data from different available genomics experiments. Given a collection of input data D from different data sources, \(D=\{{D}_{k}{|k}=1,\ldots ,3\}\) (here, ensemble Hi-C, lamina DamID and SPRITE; see data in Supplementary Note 1, section 4 ‘Methods for integrated genome structure modeling’), we aim to estimate the structure population X such that the likelihood \(P(\{{D}_{k}\}{|X})\) is maximized. To represent missing information at the single-cell and homologous chromosome level, we introduce data indicator tensors \({D}^{* }=\{{D}_{k}^{* }{|k}=1,\ldots ,K=3\}\), which augment missing information about allelic copies in single cells. Thus, the latent variables are a detailed expansion of the diploid and single-structure representation.

To determine a population of 3D genome structures consistent with all experimental data, we formulate a hard expectation–maximization problem, where we jointly optimize all genome structure coordinates and all latent variables. Given {Dk}, we aim to estimate the structure population X and latent indicator variables \(\{{D}_{k}^{* }\}\) such that the likelihood P(X) \(P(X)\) is maximized. We therefore aim to find the optimal structures and the optimal latent variables which satisfy: \(\hat{{\boldsymbol{X}}},\hat{{{\mathfrak{D}}}^{* }}\,=\,\mathop{\text{argmax}}\limits_{{\boldsymbol{X}},{{\mathcal{D}}}^{* }}\,P({\mathfrak{D}},{{\mathfrak{D}}}^{* }|{\boldsymbol{X}})\,=\,{\rm{\arg }}\mathop{\max }\limits_{{\boldsymbol{X}},{{\mathcal{D}}}^{* }}\,{\prod }_{k}P({{\mathcal{D}}}_{k}|{{\mathcal{D}}}_{k}^{* },{\boldsymbol{X}})\cdot {\prod }_{k}P({{\mathcal{D}}}_{k}^{* }|{\boldsymbol{X}})\). This is a high dimensional, hard expectation–maximization problem and it is solved iteratively by implementing a series of optimization strategies for scalable and effective model estimation. Any iteration first optimizes the latent variables, by using the input data {Dk} and the coordinates of all genomic regions X(t) from the previous iteration step, that is, \({{{\mathfrak{D}}}^{* }}^{(t+1)}={\mathrm{argmax}}_{{{\mathfrak{D}}}^{* }}P({\mathfrak{D}}|{{\mathfrak{D}}}^{* },{{\boldsymbol{X}}}^{t})P({{\mathfrak{D}}}^{* }|{{\boldsymbol{X}}}^{t})\). Then, coordinates of the genomic regions are optimized, based on the data deconvolution D*(t), that is, \({{\boldsymbol{X}}}^{t+1}={\mathrm{argmax}}_{X}P({\mathfrak{D}}|{{{\mathfrak{D}}}^{* }}^{(t)},{\boldsymbol{X}})P({{{\mathfrak{D}}}^{* }}^{(t)}|{\boldsymbol{X}})\), and additional constraints such as the volume confinement effect by the nuclear envelope, chromosomal chain connectivity and excluded volume. The process is iterated until convergence is reached. Overall, the data deconvolution process ensures that the structure population expresses the single-cell variability of genome organization, while also aggregately reproducing the ensemble behaviour (for example, the ensemble contact probabilities). Details on the probabilistic formulation underlying the optimization process and how that is designed and implemented for the different data sources can be found in a previous report81 and its accompanying supporting information.

Structural features

The population of 1,000 single-cell 3D genome structures was used to calculate a host of structural features f that characterize the folding of each genomic region. All features and their cell-to-cell variability are calculated as described previously81,83, unless otherwise noted.

Variability

If applicable, cell-to-cell variability \(\delta {f}_{I}\) of structural feature f for a chromatin region I (from chromosome c) is defined as: \(\delta {f}_{I}=\frac{\sigma {[f]}_{I}}{\underline{\sigma }{[f]}_{c}}\), \(\sigma {[f]}_{I}\) indicating the s.d. of the feature value across the population and \(\underline{\sigma }{[f]}_{c}\) being the mean s.d. of the feature values of all regions within the same chromosome. \(\delta {f}_{I} > 0\) (\( ) indicates high (low) variability of that feature at locus I.

RAD, the normalized average radial position, and \(\delta {RAD}\), its cell-to-cell variability, is calculated as the normalized radial distance of a locus I to the nuclear centre averaged over all structures in the population:

$${\mathrm{RAD}}_{{I}}=\frac{1}{S}\sum _{s}\frac{1}{2}\sum _{i\in I}{r}_{{is}}$$

\({r}_{\mathrm{is}}^{2}={\left(\frac{{x}_{{is}}}{a}\right)}^{2}+{\left(\frac{{y}_{{is}}}{b}\right)}^{2}+{\left(\frac{{z}_{{is}}}{c}\right)}^{2}\) being the squared radial distance of locus i in structure s, and (a,b,c) being the nuclear semi-axes. The cell-to-cell variability of the radial position is defined \(\delta {RA}{D}_{I}\).

Local folding properties

These features encode local properties of the chromatin fibre and chromatin-chromatin interactions.

-

Local chromatin fibre compaction (Rg) indicates the chromatin local compactness. If \({R}_{g}[i,s]\) indicates the radius of gyration of a 1 Mb chromatin segment centred at the locus of interest in structure s, then

$${Rg}[I]=\frac{1}{S}\sum _{S}\frac{1}{2}\sum _{i\in I}{R}_{g}[i,s]$$

The compaction variability is denoted with \(\delta {Rg}\).

-

ICP indicates the average fraction of trans interactions out of all contacts formed by a genomic region I,

$$\mathrm{ICP}[I]=\frac{1}{S}\sum _{S}\frac{1}{2}\sum _{i\in I}\frac{{n}_{i,\mathrm{trans}}^{s}}{{n}_{i,\mathrm{trans}}^{s}+{n}_{i,\mathrm{cis}}^{s}}$$

\({n}_{i,\mathrm{trans}}^{s}({n}_{i,\mathrm{cis}}^{s})\) being the number of trans (cis) contacts formed by region i in structure s.

-

ILF indicates the fraction of structures in which a locus I (either copy) occupies an inner position,

$$\mathrm{ILF}[I]=\frac{1}{S}\sum _{S}\theta \left({\rm{R}}{\rm{A}}{{\rm{D}}}_{i}\le \frac{1}{2}\mathrm{or}\,{\mathrm{RAD}}_{{i}^{{\prime} }}\le \frac{1}{2}\right)$$

with θ being the Heaviside function

-

Median trans AB ratio (transAB): for each chromatin region i we define its trans A \({n}_{{is},A}^{t}\) and B \({n}_{{is},B}^{t}\) neighbourhoods as \({n}_{{is},A}^{t}({n}_{{is},B}^{t})\,=\) \(\#\{j:\mathrm{chr}[i]\ne \mathrm{chr}[j]\wedge |{x}_{{is}}-{x}_{{js}}|\le 500\,\mathrm{nm}\wedge j\in A(B)\};\) \(j\in A/B\) indicates locus j is assigned to compartment A/B. The median trans AB ratio for that region across the population is computed by pooling the values from all homologues and structures,

$${\mathrm{transAB}}_{I}=\mathrm{median}\left[\{\frac{{n}_{{is},A}^{t}}{{n}_{{is},B}^{t}}{\}}_{i\in I,s}\right]$$

The values are then rescaled so that \(0\le {\mathrm{transAB}}_{I}\le 1\).

Prediction of nuclear body locations using Markov clustering

A chromatin interaction network (CIN) is calculated for nuclear body-associated chromatin regions as described previously83. Speckle-associated chromatin regions are defined as the top 10% 200-kb regions with highest SON-TSA–seq signal; nucleolus-associated chromatin regions are 200-kb regions that overlap with nucleolus-organizing regions identified previously149. Spatial partitions of nuclear bodies are further calculated by the Markov clustering algorithm (MCL). Specifically, MCL clustering is performed for each nuclear body’s CIN with mcl tool in the MCL-edge software150. Speckle locations are defined as the geometric centre of speckle partitions identified by MCL in speckle CINs. nucleolus locations are identified following the same protocol in nucleolus CINs. Only spatial partitions with size larger than three chromatin regions are considered for downstream analysis.

Structure features defining the location of genomic regions with respect to nuclear bodies and compartments

SpD, NuD and LaD define the population-averaged distance of a genomic region to the nearest nuclear speckle, nucleolus or the nuclear envelope, respectively, while SAF, NAF and LAF quantify the frequency with which a genomic region is in association with a speckle, nucleus or the nuclear envelope in the population of cells. Approximate locations of nuclear speckles and nucleoli are predicted in each single-cell structure according to a procedure described previously83. Specifically, we identified locations of nuclear bodies in single cells by the geometric centres of highly connected subgraphs determined from a CIN, where each node represents a chromatin region with a high probability to be associated with a specific nuclear body and edges if their distances is smaller than an interaction cut-off. Details of the procedure are described previously83.

-

The average distance to the lamina (LaD) and its cell-to-cell variability (\({\delta }{\rm{LaD}}\)) is the (normalized) radial distance of a locus I to the nuclear lamina averaged over the cell population:

$${\mathrm{LaD}}_{I}=\frac{1}{S}\sum _{s}\frac{1}{2}\sum _{i\in I}{(1-r}_{{is}})$$

The cell-to-cell variability is defined by \(\delta {{\rm{L}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{D}}}_{I}\)

-

Average distances to closest speckle (SpD) and nucleolus (NuD) and their cell-to-cell variabilities (\(\delta \mathrm{SpD},\delta \mathrm{NuD}\))

$${\mathrm{SpD}}_{I}=\frac{1}{S}\sum _{s}\frac{1}{2}\sum _{i\in I}{d}_{{is}}^{\mathrm{Sp}},{\mathrm{NuD}}_{I}=\frac{1}{S}\sum _{s}\frac{1}{2}\sum _{i\in I}{d}_{{is}}^{\mathrm{Nu}}$$

where \({d}_{{is}}^{\mathrm{Sp}}({d}_{{is}}^{\mathrm{Nu}})\) is the distance of genomic region i to the predicted closest speckle (or nucleolus) in structure s. The related variability across the population is \(\delta {\mathrm{SpD}}_{I}\) (\(\delta {\mathrm{NuD}}_{I}\)).

-

For association frequencies with nuclear bodies (SAF, LAF, NAF), the SAF is defined as:

$${\mathrm{SAF}}_{I}=\frac{1}{S}\sum _{s}\frac{1}{2}\sum _{i\in I}\theta ({{d}^{\mathrm{Sp}}}_{{is}}\le {d}_{\mathrm{Sp}})$$

where dSp = 500 nm and θ is the Heaviside distribution. Analogous formulas are valid for association frequencies of genomic regions with the lamina (LAF) and nucleoli (NAF):

$${\mathrm{LAF}}_{I}=\frac{1}{S}\sum _{s}\frac{1}{2}\sum _{i\in I}\theta ({{d}^{\mathrm{Lam}}}_{{is}}\le {d}_{\mathrm{Lam}}),{\mathrm{NAF}}_{I}=\frac{1}{S}\sum _{s}\frac{1}{2}\sum _{i\in I}\theta ({{d}^{\mathrm{Nu}}}_{{is}}\le {d}_{\mathrm{Nu}}),$$

with dLam = 0.2 rad and dNu = 1,000 nm.

Calculation of enrichment scores for expression/genes/SPIN groups for structure features

All structure feature values are min–max normalized to scale the feature value to a 0–1 range. For structure features RAD, SpD and NuD, the normalized value is subtracted by 1 to signify lower value for closer proximity to the respective nuclear bodies.

To calculate the enrichment fold of a structure feature in a selected group (either selected based on gene expression, genes, SPIN and so on), we calculated the log2-transformed ratio of the feature mean within this group over the average mean value calculated from 100 random permutations of chromatin regions in the genome.

Dimension reduction of structural features with t-SNE

Structure features RAD, LAF, TransAB, RG, SpD, ICP are normalized by Z-score and combined in feature vector for each genomic region. The t-SNE algorithm in the Python scikit-learn library is then applied to the structure feature vector of all chromatin regions with the following parameters: verbosity level of 1, perplexity of 80, maximum of 300 iterations for the optimization and random state seed of 123 to ensure reproducibility. The first two components are selected for 2D visualization.

WTC-11 scHi-C data analysis

We used SnapHiC100 to identify chromatin loops at 10-kb resolution with genomic distances of 100 kb to 1 Mb. In total, 5,390 chromatin loops were detected, and the loop strength in each single cell was quantified using normalized contact probabilities (z-scores). We then applied Higashi98 to infer A/B compartments and TAD-like domain boundaries at 50-kb resolution. Finally, we performed integrative analyses of chromatin loops, compartments and TAD-like domains across the 188 WTC-11 single cells.

Categorization of genes by expression levels

Gene-level expected counts were estimated using the RSEM package from alignment BAM files and normalized using the NOIseq R package into reads per kb per million mapped reads (RPKM) values. Among genes with non-zero RPKM values, the 25th percentile of RPKM values (expression Q1) and 75th percentile (expression Q3) of RPKM values were used as thresholds. Genes with RPKM > 0 and Q3 were classified as highly expressed.

Categorization of class I and II genes

Class I and II genes were defined based on speckle association frequencies (SAFs). All 200-kb regions in the genome were divided into SAF quartiles. Class I genes are highly expressed genes in regions of the upper SAF quartile (that is, top 25%, above SAF Q3), and class II genes are highly expressed genes in regions of the bottom SAF quartile (that is, bottom 25%, SAF Q1).

Average Hi-C contact decay profiles around TSS for class I and II genes

For class I and class I genes, each gene’s annotated TSS was assigned to its corresponding 10 kb genomic bin in the Hi-C contact matrix (cool file). For each TSS, we extracted contact counts between this bin and all 10-kb bins within ±2 Mb up/downstream to generate a per-gene contact count profile. Profiles are then aligned at the TSS and averaged across all genes in within the same class to produce mean contact frequency decay profiles for class I and class II genes.

Spatial enhancer count per TSS

The spatial enhancer count for a given TSS is defined as the number of active enhancer regions within all 200 kb genomic loci (modelled as hard spheres with a 118-nm radius) whose geometric centres lie within a 350-nm distance of the TSS-containing region. Counts are stratified into all intrachromosomal, ultra-long-range intrachromosomal (>1 Mb) and interchromosomal regions.

Calculated enhancer features

Calculated enhancer features in Supplementary Fig. 7 were as follows. E: the number of active enhancers within a 200-kb window where the gene TSS is located. E/G: the number of active enhancers within a 200-kb window normalized by the total number of transcription starts sites of genes. EN_Inter/G: the number of active enhancers from other chromosomes that are located within a spatial distance of 350 nm, normalized by the number of transcription starts sites of genes within the local 200-kb window. EN_Intra/G: the number of active enhancers within the same chromosome that are located within a spatial distance of 350 nm, normalized by the number of transcription starts sites of genes within the local 200-kb window. EN_Intra(

Methods for single-cell 3D genome analysis

Cell culture

The modified WTC-11 (GM25236) hiPS cell line with GFP tagged AAVS1 locus (clone 6 and clone 28) was cultured following the 4D Nucleome-approved standard operating procedure (https://data.4dnucleome.org/protocols/d5889062-ec16-4246-9606-8d51f6b02dfa/) with two minor differences: (1) For penicillin–streptomycin, 15140-122 (Gibco) was used with a final concentration of 1% (v/v); (2) the density of seeding cells into six-well plate was 50,000–100,000.

Generating scHi-C data

The scHi-C libraries were prepared using methods previously described with slight modifications151 In brief, 1–3 million cross-linked WTC-11 cells were first lysed and permeabilized by 0.5% SDS. The cells were then incubated overnight at 37 °C with 300 U MboI followed by proximity ligation with T4 ligase at room temperature with slow rotation for 4 h. Then the nuclei were stained with Hoechst and the single 2N nuclei were sorted by FACS into wells of 96-well plate. After overnight reverse crosslinking at 65 °C, the 3C-ligated DNA in each cell was amplified using the GenomiPhi v2 DNA amplification kit (GE Healthcare) for 4.5 h. After purification with AMPure XP magnetic beads and quantification, 10 ng WGA product was used to construct a library with Tn5. The detailed experimental procedures can be found in the 4D Nucleome portal (https://data.4dnucleome.org/protocols/3286b08d-d1d6-4853-a201-7dd08400d357/).

The SBS polymer model of the studied DPPA locus

To investigate at the single-molecule level the 3D folding of the DPPA locus (chromosome 3: 108.3 Mb–110.3 Mb) in WTC-11 pluripotent stem cells, we used the strings and binders (SBS) polymer model93,95. In the SBS, a chromatin region is represented as a self-avoiding polymer chain of beads, along which different types of binding sites are located for diffusing cognate molecular binders that can bridge them. The specific attractions between the binders and the polymer binding sites drive the folding of the system through thermodynamic mechanisms of polymer phase separation94. The model binding domains are determined by using the PRISMR algorithm, which infers the optimal, that is, minimal, sets of different types of polymer binding sites by taking as input only bulk Hi-C contact data139. In our studied 2 Mb wide DPPA locus, PRISMR returned ten different binding domains. To derive a statistical ensemble of in silico DPPA single-molecule 3D conformations, we performed massive molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. In the MD implementation of the model, the system of polymer beads and binders is subject to a stochastic Langevin dynamics based on classical interaction potentials of polymer physics with standard parameters94,152. We ran the SBS simulations up to 108 MD time iteration steps, when stationarity is fully reached. To ensure statistical robustness, we collected up to 103 independent model conformations in the steady-state. We used the free available LAMMPS software (v.30july2016) to run MD simulations highly optimized for parallel computing153.

Methods for analysis of relation among A/B compartments, SPIN states, TADs/subTADs, loops and replication timing

A/B compartment detection

We called compartments in Hi-Cv2.5 data generated from H1 cells42 (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFIOUDCJRH/) through eigenvector decomposition on each 25-kb chromosomal balanced matrix. We then normalized each matrix by an expected distance dependence mean counts value with removal of rows or columns with less than 2% non-zero counts coverage. We transformed to a z-score each off-diagonal count and a Pearson correlation matrix was computed. Subsequently, we performed eigenvector decomposition on the z-scored Pearson correlation matrix using LA.eig() (linalg package in numpy), selecting the eigenvector with the largest eigenvalue. We identified inflection points demarcating boundaries of compartments by genomic coordinates with a transition in eigenvector sign. We assigned compartments to either an A or B identity by collecting intervals of same eigenvector sign orientation (positive or negative) and counting total number of unique genes per direction then reassigning those with greater gene number intersection as A and the lesser as B.

TAD and subTAD detection

We called TADs and subTADs as previously reported107,108,154,155 in 10-kb binned Hi-Cv2.5 data generated from H1 cells (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFI82R42AD/) using 3DNetMod (https://bitbucket.org/creminslab/cremins_lab_tadsubtad_calling_pipeline_11_6_2021), as previously described (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFIR94OF6S/).

Dot detection

We used dots indicative of loops called in Hi-C data from H1 cells (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFIEEF14ST/) as recently described using our published methods (https://bitbucket.org/creminslab/cremins_lab_loop_calling_pipeline_11_6_2021/src/initial/)108,155. Using geometric donut-shaped, lower-left, vertical and horizontal filters (parameters: p = 2 bins, w = 10 bins), we compute an expected interaction frequency for every given bin–bin pair. We computed P values for each bin–bin pair using a Poisson distribution and corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. The final clusters were identified using dynamic FDR thresholding.

SPIN-centric intersection with A/B compartments

We stratified H1 cell SPIN states into compartment A or B if they either co-register with a Jaccard index of greater than 0.70 or are embedded within a compartment. All other SPINs partially overlapping compartments were assigned into an ‘other’ category.

TAD/subTAD-centric intersection with SPIN states

We used H1 cell dot and dotless TADs and subTADs previously described (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFIW5EIIO2/ and https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFIU7GTTMW/)108. We classified dot TADs and subTADs as those in which loops intersect the midpoint (that is, apex of the TAD/subTAD triangle) ±20% the size of the domain. All of the remaining TADs and subTADs were assigned as dotless. We then intersected dot and dotless TADs and subTADs with SPIN states. All those with a Jaccard index of greater than 0.70 were stratified as co-registering or residing within a SPIN state. We then further stratified dot and dotless TADs co-registered/embedded within SPINs into those that were further co-registered/embedded within A or B compartments with Jaccard index of greater than 0.70. All TADs and subTADs not co-registered/embedded in SPINs nor co-registered/embedded in compartments were assigned into an ‘other’ category.

RNA-seq and iMARGI

We used RNA-seq (https://www.encodeproject.org/experiments/ENCSR537BCG/) and iMARGI (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFI2LXIREI/ and https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFIOYVWEYZ/) data generated in H1 cells. iMARGI’s RNA-end reads represent nuclear transcripts78. The RNA-end and DNA-end reads were processed with iMARGI-Docker77 and mapped to the human hg38 reference genome and processed as described. See data availability through the 4D Nucleome portal below.

High-resolution 16-fraction Repli-seq

We used 16-fraction Repli-seq data from H1 cells (https://data.4dnucleome.org/experiment-sets/4DNESXRBILXJ/) processed as described into normalized and scaled data arrays (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFI3N8GHKR/)108. The Repli-seq experiment was performed using an antibody against BrdU (anti-BrdU BD 555627, 1:100). We identified IZs (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFIRF7WZ3H/) as described previously108. Raw counts in each fraction (Si,j) were normalized by sequencing depth by virtue of read per million (RPM) such that Snorm,j,50kb_bin = Sj,50kb_bin/Si,j × 106. Repli-seq arrays were subsequently constructed from RPM bedgraphs to form 16 rows with each row representing an S phase fraction and each column representing a 50-kb bin. The array was smoothed by applying a Gaussian filter and scaled such that each column sums to 100.

Data visualizations

We visualized h1ESCv2.5 Hi-C (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFI82R42AD/) counts at SPIN state calls or dot and dotless TADs and subTADs by adding 60% of the size of the domain or SPIN to the edges of the maps and stretching to a defined length L. Each domain or SPIN was used once in the visualization and the counts in every pixel were normalized to the mean distance dependence expected value and then averaged across all 2D matrices. We similarly visualized high-resolution 16-fraction Repli-seq, total RNA-seq, iMARGI and compartment eigenvectors resized to the same intervals as TADs, subTADs or SPIN states. The signal for high-resolution 16-fraction Repli-seq is the average pileup; for total RNA-seq and iMARGI, the signal is the median pileup of averaged plus and minus strands. The compartment eigenvector is the mean pileup signal. We resized to defined length L with the resize() method in OpenCV image package (https://pypi.org/project/opencv-python/).

IZ resampling test

We computed the proportion of early and late IZs intersecting with dot TAD/subTAD boundaries (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFIWNJ5RR7/), dotless boundaries (https://data.4dnucleome.org/files-processed/4DNFIT6QE9YU/) and no boundaries. To create a null set of IZs, we computationally sampled the genome for random intervals matched by number, size and A/B compartment distribution of real early or late IZs. We created a null distribution by sampling 1.5 × 108 times and computing a one-tailed empirical P value as the area under the null distribution to the right of the real IZs. We used only null and real IZ sets in autosomal regions with sufficient counts for the statistical test by filtering unmappable telomeric/centromeric regions.

Chromatin dataset processing

CUT&Run datasets were processed by trimming adaptors using cutadapt, locally mapping the reads using bowtie2, filtering for quality, removing duplicates and ENCODE blacklisted regions (ENCFF419RSJ) using samtools, and computing the coverage using deeptools. The average chromatin landscape at IZs was computed using HOMER on a 1 Mb region centred on each IZ centre and plotted using R. The chromatin profile was plotted using the WashU browser and IGV on chromosome 2: 20404583–58108703.

IZ integration with chromatin and transcription

HCT116, H1 and mES cell IZs were grouped by replication timing by splitting the corresponding Repli-seq data into quartiles. Matching random regions were generated by shuffling the IZs regions within their respective replication timing quartile using bedtools. Insulation score at IZs and random regions were computed by extracting the minimum insulation score in each IZ or random region using bedtools. Accessibility at IZs and random region was computed by extracting the total ATAC–seq signal at each IZ or random region using bedtools. H1 cell RNA-seq data were processed by mapping reads on hg38 using Hisat2, filtering for quality using samtools and computing the coverage using bedtools. Expression at IZs and random regions was computed by extracting the total RNA-seq coverage (adding plus and minus strands for the H1 cell RNA-seq) at each IZ or random region using bedtools. The H1 cell CUT&Run chromatin marks dataset was processed by trimming adaptors using cutadapt, locally mapping the reads using bowtie2, filtering for quality, removing duplicates and ENCODE blacklisted regions using samtools and computing the coverage using deeptools. The average chromatin marks at IZs and a random region were computed using HOMER on a 1 Mb region centred on each IZ centre. Figures were plotted using R.

Methods for predicting Hi-C maps from sequence (Akita)

Two convolutional neural network models with the Akita architecture124 were trained, one on H1 cells and one on HFFc6 Micro-C data. Micro-C data were downloaded from the 4D Nucleome data portal156 and processed as previously described124. The coordinates of the deletion at the TAL1 locus with experimentally verified changes on genome folding was obtained from a previous study157. The deletion was centred and systematically extended on both sides to get the input sequence for Akita (220 bp).

FIMO158 was used to scan the human genome (hg38) to identify the potential binding sites (P −5) of cell-type-specific TFs POU2F1–SOX2 (MA1962.1) and FOSL1–JUND (MA1142.1) using their annotations in the JASPAR database159. TAD boundaries in the Micro-C datasets at 5-kb resolution were downloaded from the 4D Nucleome data portal. The ones that were not shared between the cell types (no boundary in the other cell type within 20 kb) were identified as cell-type-specific TAD boundaries. The binding sites overlapping cell-type-specific TAD boundaries of each cell type were extracted using bedtools160. In silico mutagenesis was performed on the resulting binding sites by replacing the motifs with random sequences to evaluate their effects on predicted genome folding. Motif logos were visualized using the contribution scores of the motifs, which were computed by DeepExplainer (DeepSHAP implementation of DeepLIFT)128,161.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.