One small change in battery design could reduce fires, researchers say

Lithium-ion batteries are found in everything from smartphones to cars, and while they are generally very safe if stored and charged correctly, there are thousands of documented cases of them catching fire — sometimes with deadly consequences.

Lithium-ion batteries contain flammable electrolytes — liquid solutions of lithium salts dissolved in organic solvents that allow the electric charge to flow. The batteries can become unstable under certain conditions, such as physical damage like piercing, overcharging, extreme temperatures or manufacturing defects. When things go wrong, a battery can heat up and catch fire very rapidly, undergoing a dangerous chain reaction called a “thermal runaway.”

Commercial aviation is especially exposed to the problem, because of how ubiquitous battery-powered gadgets are on planes and how dangerous a fire in the cabin or cargo hold can be. In the US, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has long prohibited carrying spare lithium-ion batteries in checked baggage and mandates that all batteries brought into the cabin must remain accessible. The agency recorded 89 battery incidents involving smoke, fire or extreme heat on passenger and cargo aircraft in 2024, and 38 in the first half of 2025.

These incidents can lead to the total loss of an aircraft, like the Airbus A321 that was gutted by flames in January in Busan, South Korea. The fire was likely started by a power bank stored in an overhead compartment, according to investigators, which has led some airlines to ban the devices.

But the risks of thermal runaways extend to homes, particularly vulnerable to e-bike or e-scooter battery fires, and businesses of all kinds: a survey conducted by insurance provider Aviva in 2024, among over 500 UK businesses found that just over half had experienced an incident linked to lithium-ion batteries, such as sparking, fires and explosions.

Researchers all over the world are working to solve the problem by developing safer batteries, for example by replacing the liquid electrolyte with a more fire-resistant solid or gel. However, such solutions require significant changes to current production lines, an obstacle to widespread adoption.

Now, a team of researchers from The Chinese University of Hong Kong has proposed a change in lithium-ion battery design that could rapidly integrate into current manufacturing methods, because it simply involves swapping chemicals in the existing electrolyte solution.

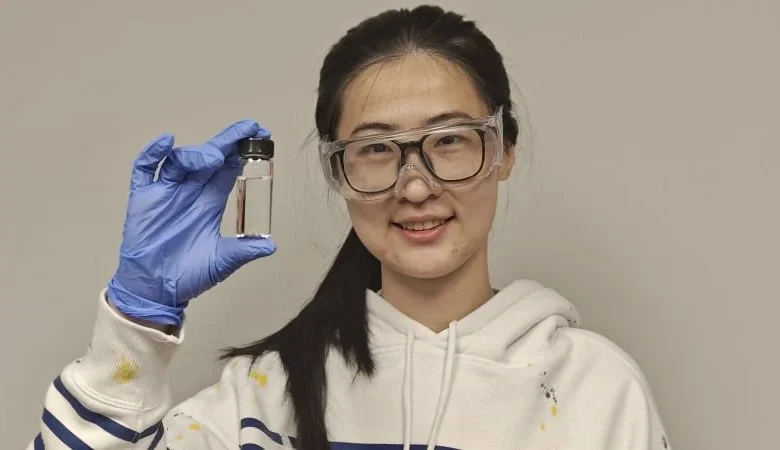

The method was detailed earlier this year in a study led by Yue Sun, now a postdoctoral fellow at Virginia Tech: “I think the most difficult thing for people to realize about batteries is that when you try to optimize performance, sometimes you compromise safety,” she said, explaining that increasing performance requires a focus on chemical reactions that happen at room temperature, while increasing safety focuses on reactions that happen at high temperatures.

“So we came up with an idea to break this trade off by designing a temperature-sensitive material, which can provide a good performance at room temperature, but can also offer good stability at high temperatures.”

Battery fires generally start when part of the electrolyte breaks down under stress and releases heat in a chain reaction. Sun and her colleagues’ design uses a new electrolyte that includes two solvents to stop this chain reaction in its tracks.

At room temperature, the first solvent keeps the battery’s chemical structure tight, optimizing performance, but if the battery starts to heat up, the second solvent takes over and prevents a fire by loosening that structure and slowing down reactions that could result in a thermal runaway.

In lab tests, a battery with this new design that was pierced with a nail saw its temperature rise by only 3.5°C (38.3° Fahrenheit), instead of the 555°C (1,031° Fahrenheit) spike that occurred with a traditional battery. The researchers say there is no negative impact on the battery’s performance or durability, and it retained over 80% of its capacity after 1,000 charging cycles.

“Since our invention is the electrolyte, it can be easily implemented into commercially available systems — you basically just swap in the new electrolyte,” said Yi-Chun Lu, a professor of mechanical and automation engineering at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, and one of the authors of the study.

“In the manufacturing process, the most difficult aspect is the electrodes, or the solid part. But the electrolyte that we are swapping is a liquid, so you can directly inject it into the cell without any new equipment or new process,” Lu added.

The new chemical recipe would slightly increase the manufacturing cost, but Lu said that at scale, the price would be “at a very similar level” to current batteries. The researchers are interested in pursuing the idea commercially, and are currently in discussion with battery manufacturers to bring the design to market, which could take between three to five years, according to Lu.

In tests, the researchers made a battery large enough to power a tablet, but Lu said that there needs to be more “validation” to scale the design up to the size required for cars, for example.

Researchers in the field of lithium battery safety who didn’t participate in the study expressed positive views of the work when contacted by CNN for comment. Donal Finegan, a senior scientist at the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory, said in an email that the new design is an exciting development, and it translates into a safety battery that can tolerate hot conditions and short circuiting without causing a fire: “The strategically chosen electrolyte solution is scalable and does not significantly impede the cycle life of the battery, which helps eliminate many barriers towards mass adoption in commercial battery systems,” he added.

The study explored a range of electrolyte compositions and found options where there was a balance between battery cells lasting many cycles while also maintaining stability at higher temperatures, according to Gary Koenig, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Virginia. “From a manufacturing perspective, implementing a new electrolyte can be achieved in a relatively short timeframe as long as there is not an unforeseen processing compatibility issue,” he said in an email.

Jorge Seminario, a professor of chemical engineering at Texas A&M University, said in an email that the new design addresses one of the most critical challenges in high-energy lithium-ion batteries, which is achieving both safety and performance: “The study is highly innovative and impactful, offering a practical solution to a critical bottleneck in lithium-ion battery safety,” he added.