A rural jobs law without a guarantee

- The replacement of MGNREGA with a new law has sparked protests, with labourers saying work has stopped and wages remain unpaid.

- The new law promises more workdays but weakens the guarantee. Critics say it limits universality, centralises control and shifts financial risk to states.

- Experts argue that the challenges related to MGNREGA were in implementation. Scrapping a proven safety net could deepen rural distress.

See All Key Ideas

Mandeshri Devi, 60, from Mahanth Maniyari village in Muzaffarpur district, and her two daughters-in-law, work as daily-wage labourers. Her two sons earn a living as masons. The family depends on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) for work, a large-scale rural employment programme that guarantees up to 100 days of wage work per household.

“We barely get 30 to 40 days of work in a year, even though we are entitled to 100 days,” she says. “Still, the ₹20,000–25,000 we earn through MGNREGA is a big relief for our family.”

Now, Mandeshri Devi is protesting in Muzaffarpur, Bihar, along with hundreds of other workers. They say work has stopped since the centre introduced the Viksit Bharat — Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) (VB–G RAM G) Bill, which replaces MGNREGA. Another protester, Rinku Devi, says she has not been paid wages for work she completed three months ago. “Now, there is no work either,” she adds.

The protest began on January 2, says Sanjay Sahni, activist and convener of MNREGA Watch in Muzaffarpur. According to him, work stopped soon after the Bill was passed in Parliament. “Local officials are telling workers that it will take six months for new directives under VB–G RAM G to come. Until then, they say, labourers must wait,” Sahni says. Workers from 16 blocks of the district are participating in the protest.

“There are two demands,” Sahni says. “First, restore work immediately. Second, repeal the new law and bring back MGNREGA.” Economist Jean Drèze also joined the protest on January 7.

Protesters in Muzaffarpur, where demonstrations began on January 2, are demanding the restoration of work under MGNREGA. Image courtesy of Sanjay Sahni.

Similar complaints are emerging from other states. Around 700 km away, in the Sitapur district of Uttar Pradesh, daily-wage workers say work has slowed or stopped. Gokaran Prasad, 58, from Gopalpur village, says he has not received work in recent weeks.

Om Prakash, associated with the Sangtin Kisan Mazdoor Sangathan, says officials earlier cited technical problems with the MGNREGA website. “Now they say the app is being reworked,” he says. “One excuse or another is being used to deny work.”

Workers say these delays began after the government moved to replace MGNREGA with the VB–G RAM G law.

While the central government has described the move as a major reform in rural employment and development, it has triggered protests in several states. Political parties, including the Congress and the Aam Aadmi Party, have organised demonstrations in several states.

Sahni says MGNREGA was the outcome of years of work by political parties, civil society groups and grassroots movements. “That collective effort is needed again to bring it back.”

Manoj Kumar Jha, a Rajya Sabha member from the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), says MGNREGA repeatedly proved its value during crises. “Whether during droughts or the pandemic, demand for work always rose,” he says. “That was the strength of the law. With one stroke, the government has changed that.”

“In fact, before killing MGNREGA, they (government) have written the obituary of the programme through this bill,” Jha adds who wrote a letter to fellow parliamentarians on December 18 urging them to oppose the bill.

MGNREGA, though primarily an employment guarantee act, has also functioned as a local climate action instrument on the ground, with most of its 260 permissible works linked to natural resource management. With it being repealed and replaced by the VB–GRAM G Act, which experts say is more centralised and does not offer a legal guarantee of jobs, it is unclear whether there will be similar environmental benefits.

Villagers desilt a community water tank under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). The central government has replaced the employment guarantee law with a new Act. Image by McKay Savage via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-2.0).

A law without a guarantee

The central government introduced the bill in the Lok Sabha on December 16, and the debate continued late into the night of December 17. It was taken up and passed in the Rajya Sabha on December 18 and received the President’s assent on December 21.

The new law promises 125 days of work per rural household whose adult members volunteer to undertake unskilled manual labour, up from the 100 days guaranteed under MGNREGA, though critics say that the new law no longer offers a legal guarantee.

Employment generation, under the new law, is tied to infrastructure creation through four priority areas: water-related works, core rural infrastructure, livelihood-related infrastructure, and special works to address extreme weather events.

However, labour rights groups have raised concerns about both the process and substance of the law. Raj Shekhar, co-convener of the Right to Food Campaign and based in Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh, says the bill was introduced without adequate public discussion. “Till December 13, no one knew such a bill was coming. News broke on December 14, initially suggesting only a name change. It later became clear that an entirely new law was being brought in,” he says. “This is not how legislation should be made in a democracy.”

Nikhil Dey of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan, which played a pioneering role in shaping MGNREGA, says two distinct issues are at play and should be seen separately. “First, the Employment Guarantee Act has been repealed. Second, a new law is being presented as a replacement, even though it is not an employment guarantee at all,” he says.

The claim that the new law merely changes the name while increasing employment to 125 days is misleading, Dey adds.

Section 5 of the act states that it will apply only in areas notified by the central government. “This immediately ends the universality that was central to MGNREGA,” Dey says. “The guarantee no longer applies everywhere by default.”

At the same time, the law mandates a 60-day no-work period during peak agricultural seasons. State governments are required to notify the period in advance. Experts argue that this provision weakens workers’ bargaining power. “It ensures that large employers can access labour at the rates they want,” Dey says.

MGNREGA had strengthened rural wages and thus the bargaining power of labourers. “We repeatedly heard complaints from large landholders and factory owners that MGNREGA disrupted their labour supply because workers refused to accept extremely low wages,” he says. “That itself shows how the bargaining power of workers improved.”

Jha from RJD adds that MGNREGA came closest to fulfilling Article 41 of the Constitution, which directs the state to secure the right to work. “This nation literally struggled for decades to build such a framework,” he says.

Dey also echoes, “Taken together, this reverses nearly five decades of struggle for employment rights—about 30 years of advocacy and 20 years of implementation. What remains is a deeply centralised framework that is anti-poor, anti-worker, anti-Panchayat, and anti-state.”

Workers desilt a village pond in Asir village, Sirsa district, Haryana, under MGNREGA, now replaced by the VB–G RAM G Act, 2025. Image by Mulkh Singh via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Central control, state burden

One of the major concerns with the VB–G RAM G Act, experts say, is the change in the funding pattern. Under the new law, costs will be shared in a 60:40 ratio between the centre and the states. For northeastern states, Himalayan states, and Union Territories, including Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir, the Centre will bear 90% of the expenditure.

The law also gives the central government the authority to determine state-wise normative allocations for each financial year. Any expenditure by a state beyond this allocation will have to be borne by the state, that too as per the norms set by the centre.

“This is complete centralisation,” says Nikhil Dey. Other aspects of the law further centralised the scheme, he says, adding, “Any plan now has to fit within the Viksit Bharat framework and align with the PM Gati Shakti framework. Planning becomes top-down, not bottom-up. This effectively ends decentralised planning and local decision-making about what is needed in a particular area.”

Under the earlier MGNREGA framework, the centre covered 100% of labour costs. States could choose to avoid material-intensive construction works and still meet employment guarantees without spending their own resources. In MGNREGA, states were supposed to contribute only 25% of material costs, but now face burdens of 40% to 100% of total costs.

“The 60:40 ratio may not be sufficient when states are legally mandated to provide 125 days of work in notified areas,” Dey says.

The funding arrangement under the new act places a heavy burden on states.

The NREGA Sangharsh Morcha, a coalition of organisation, has attempted to quantify this burden using Karnataka as an example. In 2024–25, around 8.9 million households were registered under MGNREGA in the state. Only 36% of these households accessed work. On average, active households received just 45 days of work. The state spent ₹5.73 billion that year.

“If Karnataka had generated the same employment under the new act, the state expenses would add up to ₹2,729 crore (₹27.29 billion). This is over four times higher than the expenditure under MGNREGA,” the Morcha notes.

The researchers further estimate that providing 125 days of work to these households would cost around ₹75.73 billion. Extending 125 days of employment to all registered households would push the figure beyond ₹200 billion.

Rajendran Narayanan, associate professor at Azim Premji University and one of the researchers involved, says states will be forced to cut spending on other priorities. “This will come at the cost of health, education, and other social sectors,” he says. “If Karnataka, one of the richer states, struggles under this model, imagine the plight of states like Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand.”

Manoj Kumar Jha describes this as the second major blow to the employment guarantee framework. “States with weak revenue bases simply will not be able to continue the programme,” he says. “This is a clear attempt to dismantle a rights-based employment law.”

“I am a strong critic of this government,” Jha adds, “but on this issue, I will say it has been ill-advised. Mark my words, they (government) will have to take it back.”

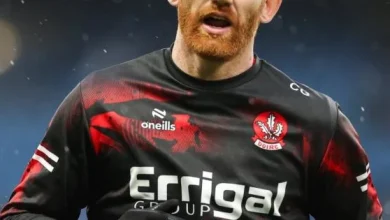

Economist Jean Drèze addresses protesters in Muzaffarpur. Image courtesy of Sanjay Sahni.

Reform or rollback?

The central government argues that the new act fixes structural weaknesses in MGNREGA. It cites corruption, payment delays, and low completion of 100 workdays as reasons for a “comprehensive legislative reset.”

Experts counter that these failures result from chronic underfunding. Narayanan points to World Bank research estimating that MGNREGA required allocations of around 1.6% of GDP to function effectively. In reality, spending moved around 0.3%. There have been protests in past against the government’s attitude towards MGNREGA, which has proved critical during crises, such as the 2008 recession or COVID.

For instance, between April 1 and May 20, 2020 (during the pandemic-related nationwide lockdown), around 3.5 million workers sought employment under MGNREGA, compared to 1.5 million during all of 2019–20, according to MicroSave Consulting, a global consulting firm.

MGNREGA also delivered long-term benefits. Of over 260 permissible works, most relate to natural resource management, including water conservation and drought-proofing, making it a key public investment in climate adaptation, too.

A recent open letter, signed by several economists and Nobel laureates, described MGNREGA as a rare programme that delivers equity at scale. It noted that over half its workers are women, and nearly 40% belong to scheduled castes and tribes.

Yet limited budgets forced officials to ration work. Even revised allocations often fell short of actual demand, experts say.

Mandeshri Devi’s experience reflects this reality. Despite enrolling for 100 days, she rarely received more than 30–40 days of work.

Experts say MGNREGA had already shifted from a demand-driven to a supply-driven model over the past decade. The new law formalises this shift and turns it into what Jha from RJD describes as a command-driven system.

Dey says the previous protests demanded better implementation of MGNREGA, not repeal. “If the government wants asset creation, it should say so clearly,” he says. “Call it an asset development programme. Do not present it as an employment guarantee.”

Read more: Study looks at India’s rural work guarantee scheme through a climate lens

Banner image: Daily wage labourers carry silt at a tank in Bhandara district, Maharashtra. Image courtesy of India Water Portal via Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).