Grateful Dead Co-Founder, Singer-Guitarist Was 78

Singer-songwriter-guitarist Bob Weir, a cornerstone of the Grateful Dead and the San Francisco psychedelic band’s many latter-day offshoots for more than half a century, has died after a long battle with cancer and lung issues, according to a social media post from his family. He was 78.

The post said that Weir had been diagnosed last summer and began treatment three weeks before Dead & Company, a spinoff group of the Grateful Dead, played a weekend of shows at Golden Gate Park to mark the original band’s 60th anniversary. Many fans believed those livestreamed concerts might be the band’s unbilled farewell engagement, but few could have guessed the conditions under which Weir powered through what turned out to be his final gigs.

“It is with profound sadness that we share the passing of Bobby Weir,” the family statement began. “He transitioned peacefully, surrounded by loved ones, after courageously beating cancer as only Bobby could. Unfortunately, he succumbed to underlying lung issues.”

The statement continued, “Bobby’s final months reflected the same spirit that defined his life. Diagnosed in July, he began treatment only weeks before returning to his hometown stage for a three-night celebration of 60 years of music at Golden Gate Park. Those performances, emotional, soulful, and full of light, were not farewells, but gifts. Another act of resilience. An artist choosing, even then, to keep going by his own design. As we remember Bobby, it’s hard not to feel the echo of the way he lived. A man driftin’ and dreamin’, never worrying if the road would lead him home. A child of countless trees. A child of boundless seas.”

Weir was just 16 years old when he befriended Jerry Garcia, then a music teacher at a Palo Alto, CA, instrument store, on New Year’s Eve of 1963. The two guitarists formed an old-time music unit, Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, and went electric with the rock band the Warlocks, before finally taking the name the Grateful Dead in 1965.

Key to the Dead’s expansive, jam-based sound was the elegant free-form interplay between lead guitarist Garcia and his deft front-line foil Weir, whose unorthodox work transcended the “rhythm guitar” label. His style was rooted in country and blues, but, as he explained in an interview with Alan Paul, it was rooted in an unlikely source.

“[M]y dirty little secret is that I learned by trying to imitate a piano, specifically the work of McCoy Tyner in the John Coltrane Quartet,” Weir said. “That caught my ear and lit my flame when I was 17. I just loved what he did underneath Coltrane, so I sat with it for a long time and really tried to absorb it. Of course, Jerry was [also] very influenced by horn players, including Coltrane.”

As a writer, Weir penned a number of songs that became cornerstones of the Dead’s concert repertoire; many were penned with his boyhood friend John Perry Barlow. His best-known compositions included “Sugar Magnolia” (a rare collaboration with Garcia’s writing partner Robert Hunter), “Playing in the Band,” “One More Saturday Night,” “Cassidy,” “The Music Never Stopped,” “Estimated Prophet” and “I Need a Miracle.”

Weir was not the dominant vocalist in the group, contributing about a third of the lead vocals, but even when Garcia was assuming those duties, he contributed to the layered harmonies that characterized the band’s most popular work. He took the lead on what is possibly the Dead’s best-known and most iconic song, “Truckin’,” a track from 1970’s “American Beauty” that contains the beloved couplet, “Lately it occurs to me / What a long, strange trip it’s been.”

Apart from the Dead, Weir recorded three solo albums; the first, 1972’s “Ace,” found him supported by most of the band. As time went on, he was increasingly involved in such band side projects as Kingfish, Bobby and the Midnites and RatDog.

After the dissolution of the Grateful Dead following Garcia’s death in August 1995, Weir was a standard bearer in various reunions including shifting lineups featuring the Dead’s core members. He played under the group rubrics the Other Ones, the Dead and Furthur.

Following 2015’s 50-year celebration Fare Thee Well in Northern California and Chicago, Weir and drummers Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart mounted a new group, Dead & Company, with singer-guitarist John Mayer, for 2015-18 tours.

With the other members of the Grateful Dead, Weir was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994.

Bob Dylan praised Weir’s unorthodox style while describing his love for the group in his book “The Philosophy of Modern Song.” “Then there’s Bob Weir,” wrote Dylan. “A very unorthodox rhythm player. He has his own style, not unlike Joni Mitchell but from a different place. Plays strange, augmented chords and half chords at unpredictable intervals that somehow match up with Jerry Garcia — who plays like Charlie Christian and Doc Watson at the same time.”

He was born Robert Hall Parber in San Francisco on Oct. 17, 1947. His birth parents, both college students, gave him up for adoption. He was raised by his adoptive parents Frederic and Eleanor Weir; the family, thanks to Weir’s work in a Bay Area engineering firm, was wealthy and socially prominent.

Initially involved in athletics as a boy, Weir became interested in music after being exposed to jazz by the family nanny. After brief studies on the piano and trumpet that disrupted the household, Weir took up the acoustic guitar at 13.

A childhood bout with spinal meningitis and severe dyslexia left him with behavioral problems and poor study habits, and he spent some of his teens in private schools; enrollment at the Fountain Valley school in Colorado, where he met his future lyricist Barlow, led to an interest in cowboy culture that would become an abiding creative influence.

The unruly Weir ultimately returned to the Bay Area, where he was enrolled in Menlo-Atherton High. He began to take a deep interest in folk music, studying guitar with Jerry Kaukonen (soon to become better known as Jorma Kaukonen, lead guitarist of Jefferson Airplane) and founded a folk group, the Uncalled Four, with his classmates.

However, Weir’s fateful encounter with Garcia, then a bluegrass banjo picker, at Dana Morgan’s music store led to the formation of a new group; Garcia and Weir, on washtub bass and jug, were joined in the enterprise by Ron McKernan, a grubby 18-year-old blues enthusiast who quickly was dubbed “Pigpen.”

By late 1964, by then under the sway of the Beatles, those musicians were joined by drummer and jazz aficionado Kreutzmann and avant garde bassist Phil Lesh in the rock unit the Warlocks. The band quickly became aligned with the burgeoning hippie counterculture in San Francisco, and played their first date as the Grateful Dead at one of writer Ken Kesey’s LSD-soaked “Acid Tests” in December 1965.

A popular early attraction at such local rock ballrooms as the Avalon and the Fillmore, the Dead were signed by label president Joe Smith to Warner Bros. Records, then an old-line pop label trying to contemporize its roster. The group’s self-titled 1967 debut album drew heavily on string band and blues material that dated back to their jug band origins.

By the time the Dead’s more overtly psychedelic sophomore album “Anthem of the Sun” was recorded in 1968 (by which time percussionist Mickey Hart had joined the group), Weir’s presence in the lineup was no longer a certainty: Both he and McKernan were under fire for their unprofessional performances, and the pair were briefly dismissed in mid-1968. However, after a handful of shows without them, the two musicians were back in the fold.

Through 1969, the Dead’s work on records leaned heavily on improvisation and eschewed traditional tight songwriting, with the two-LP package “Live/Dead” serving as a representation of the concert style beloved by the band’s rabid legion of “Dead Head” fans.

They moved into the commercial mainstream with a pair of 1970 releases, “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty,” which were filled with carefully crafted songs. The latter album, the band’s second to reach the national top 30, served as the best showcase to date for Weir’s talents as a singer and writer, and “Truckin’,” which drew its inspiration from a recent Dead drug bust in New Orleans, became an evergreen at free-form FM radio.

However, a dispute with Robert Hunter over the performance of “Sugar Magnolia” led the lyricist to work exclusively with Garcia, and moving forward Weir wrote primarily with his friend Barlow, who co-authored half the songs on Weir’s solo bow “Ace.”

Following a trio of live albums that fulfilled their commitments to Warner Bros. (and the death of McKernan from the consequences of alcoholism in 1972), the Dead inaugurated their own eponymous label, distributed by United Artists. The imprint debuted in 1973 with “Wake of the Flood,” which bore an ambitious 13-minute suite written by Weir. Though their studio albums of the period all reached the top 20, the Dead were wearied by operating their own label, and Grateful Dead Records folded in late 1976.

Signed to Clive Davis’ Arista Records in 1977, the Dead initially sold their albums to their devoted Deadheads, who seemed more interested in purchasing tickets to the band’s tribal concerts.

Weir, who had issued a 1976 studio set with Kingfish that peaked at No. 50, released his sophomore solo album “Heaven Help the Fool” in 1978; cut in Los Angeles with a cast of studio pros, it was poorly received. A pair of Bobby and the Midnights albums featuring latter-day Dead keyboardist Brent Mydland both failed to reach the top 100 in the early ‘80s.

Deadhead loyalty supplied the band with self-sustaining record sales and huge popularity as a concert attraction through the late ‘80s. However, in 1987 – two decades after the release of their debut LP — the group scored a legitimate top 40 hit, “Touch of Grey”; the No. 9 single on aging and survival pushed the album ‘In the Dark,” which contained three Weir-Barlow songs, to No. 6 and double-platinum sales.

While triumphs like a concert at Egypt’s Great Pyramids and a joint tour with Bob Dylan followed in the immediate wake of that success, the Dead’s next studio album, 1989’s ironically titled “Build to Last,” would be its final set, save for a 1990 concert package.

Garcia, who had nearly succumbed to a diabetic coma in the mid-‘80s, had struggled with heroin addiction for years, and he was found dead in a Marin County rehab clinic eight days after his 53rd birthday. In the decades that followed, Weir was a constant in the various acts that reunited former Dead members to perform the classic repertoire.

Weir released studio and live sets by RatDog, his collaboration with the late bassist Rob Wasserman, in 2000-01. He issued his third solo album “Blue Mountain,” a roots-based set co-written with singer-songwriter Josh Ritter, via Columbia/Legacy in 2016. (His collaborator Barlow died at 70 in February 2018.)

He made an appearance at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in 2016 to promote the “Blue Mountain” album, talking about his roots influences. “Jerry and I were huge into Buck Owens particularly — and Dolly Parton, we were both more than smitten,” Weir said.

But his interest in the Western culture ran deeper than that. “When I was a kid I was drawn to the cowboy culture and the American West,” he continued. “My folks used to take us up to Squaw Valley, and in the winter it was a ski resort, but in the ‘50s and early ‘60s in the summer it was a cattle ranch… I spent a lot of time at the stable, and the old cowpokes took a shine to me, showing me how to ride and a few of the skills a young cowpoke should know… When I was 15, after one summer I thought it’d be a terribly romantic thing to do to run around and be a cowboy, and so found my way out to Wyoming and got work on a ranch, where I was in a bunkhouse with a bunch of old guys who had grown up in an era before radio had gotten that far, to Wyoming. So the very notion of how to spend an evening was to pop a cork and tell stories and sing songs. I was the kid with the guitar, so I had to listen to the melody and the words and figure out where’s the next chord coming in and what it’s gonna be and be there with it, or I was going to get a little abuse. It was great ear training for a young musician. At the same time, I got steeped in a culture that just stuck with me.”

In late 2018, the singer-guitarist took to the road performing Grateful Dead material and other songs with Wolf Bros, a new trio with bassist (and Blue Note Records prexy) Don Was and former RatDog drummer Jay Lane.

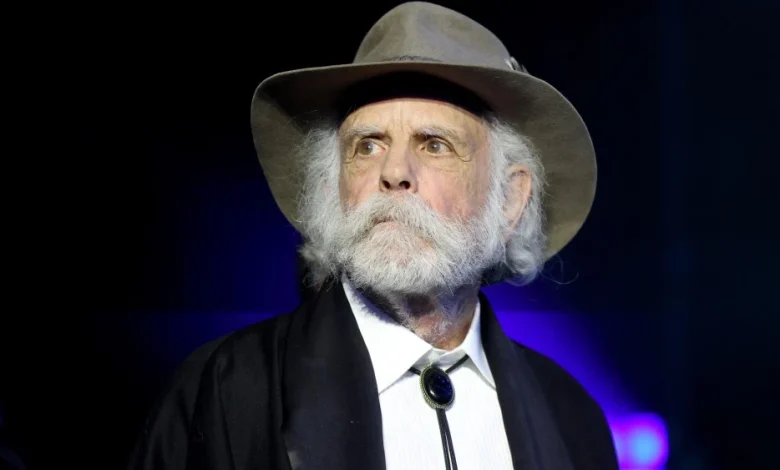

Dead & Company, the group Weir founded with other former Grateful Dead members and John Mayer to continue performing the catalog of the defunct group, had had a robust presence on the concert scene for years, before and even after a farewell tour in summer 2023. In 2024 and again in 2025, Dead & Company did highly successful multi-week residencies at Sphere in Las Vegas, and became at least as identified with the new venue as U2, who did the opening engagement.

In a June 2024 interview with Variety, Weir spoke excitedly about the just-begun debut Sphere engagement, putting the lie to any belief that, as one of the older members of Dead & Company, he might be less excited about the new technology powering the show.

“Working from the stage at the Sphere is like opera,” he said. “The storytelling facility there is really beyond about anything else. Every artist of any tribe is first and foremost a storyteller. And you can’t get this anywhere else right now. The story being told in the visuals is tangentially attached to the story that we’re telling from on stage. And from what I can, from what I can gather, it’s pretty satisfying to the audience… If you go back 50, 60 years to the Acid Tests (Ken Kesey’s visionary events in San Francisco), when they had those overhead projectors and were doing light shows with clear glass plates and oils and all that kind of stuff, they had that stuff dancing in time with the music. And I want to see if we can get that kind of thing happening… I think we’re only scratching the surface here.”

Talking about the ILM-designed opening and closing of the Sphere shows, which went from the group’s Haight-Asbury neighborhood to the outer limits of the galaxy and back again, Weir quipped, “I kind of like being in outer space. Makes me feel right at home!”

Dead & Company at Sphere in Las Vegas

Chris Willman/Variety

In-between the two Sphere residencies, Dead & Company also performed at the MusiCares Persons of the Year gala in January 20, where the core lineup of the Grateful Dead, dead and alive, was being honored.

“Longevity was never a major concern of ours,” Weir said in his acceptance speech at the MusiCares gala — getting a big chuckle out of the audience, given the group celebrating the 60th anniversary, even though he didn’t deliver it as a laugh line. “Lighting folks up and spreading joy through the music was all we really had in mind, and we got plenty of that done.”

Further on in his speech, Weir said, “The road is a rough existence, as plainly evidenced by the simple fact that there aren’t all that many of my old bandmates here tonight to receive this recognition,” Weir said, standing alongside fellow founding Dead member Mickey Hart. “But thank you, Grahame Lesh and Trixie Garcia and Justin Kreutzmann for representing your dads here,” he added, acknowledging the recent passing of Phil Lesh — who died shortly after the MusiCares honor was announced — as well as the long-gone Garcia and the recently retired Bill Kreutzmann.

Weir acknowledged at the outset of his speech that he might not get far into it without a lapse, mentioning that he grew up dyslexic, although he came through just fine in a monolog that made up for some of the lost time of rarely or never speaking from the stage.

“If making music is what you’re gonna be doing, you’ll find that you can make considerably more thunder if you can find folks to play with, and learn to work with and play off of them, and let them play you,” he told the audience. “That’s what the Grateful Dead did over the years, and success eventually came to us. All along, my old pal Jerry used to say, ‘You get some, you give some back’ — and so we did. From early on it was more than apparent to us that we could be of substantial benefit to our broader community – and have big fun doing it. We also learned right away that it was an honor and a privilege to be in this position, something we never took lightly.”

Weir is survived by his wife Natascha and their two daughters.

The family’s statement concluded: “There is no final curtain here, not really. Only the sense of someone setting off again. He often spoke of a three-hundred-year legacy, determined to ensure the songbook would endure long after him. May that dream live on through future generations of Dead Heads. And so we send him off the way he sent so many of us on our way: with a farewell that isn’t an ending, but a blessing. A reward for a life worth livin’…

“His loving family, Natascha, Monet, and Chloe, request privacy during this difficult time and offer their gratitude for the outpouring of love, support, and remembrance. May we honor him not only in sorrow, but in how bravely we continue with open hearts, steady steps, and the music leading us home. Hang it up and see what tomorrow brings.”

(With additional reporting by Chris Willman)