Making of ‘Jay Kelly’: Noah Baumbach’s Crisis of Faith in Filmmaking

Every Sunday during the shooting of Jay Kelly, Noah Baumbach‘s loving, elegiac tribute to the magic of filmmaking and the double-edged sword of stardom, he and the cast and crew would attend Movie Church.

Baumbach would screen films for the cast and crew that, thematically or stylistically, inspired his Netflix dramedy. Films like Preston Sturges’ 1941 film Sullivan’s Travels, a screwball Hollywood industry satire in which a successful comedy director yearning to make a serious movie sets off on a road trip across America. Or Ingmar Bergman’s existential 1957 drama Wild Strawberries, about a celebrated doctor traveling to receive an award, only to be confronted by memories that force him to reassess the choices that shaped his life.

In Baumbach’s film, Jay Kelly is a 60-something world-famous movie star (played by 60-something world-famous movie star George Clooney) who has a moment of crisis. He’s estranged from his father (Stacy Keach) and oldest daughter, Jessica (Riley Keough), and senses his youngest, Daisy (Grace Edwards), about to leave for Europe, is slipping away. The sudden death of the director (Jim Broadbent) who gave him his big break and a post-funeral confrontation with Timothy (Billy Crudup), an old acting-school buddy who didn’t make it, set him off.

An Italian film festival has offered Jay a lifetime achievement award. He seizes on it as an excuse to chase Daisy through Europe, accompanied by his longtime agent, Ron Sukenick (Adam Sandler), hoping to pull his family together for a career-capping celebration. But as with Isak Borg in Wild Strawberries, the ghosts of Jay’s past — the choices he made, the people he sidelined — refuse to stay behind.

Jay Kelly emerged from Baumbach’s own crisis of faith in cinema.

“I had just made [2022’s] White Noise, which was a difficult experience, partly because of COVID,” Baumbach tells The Hollywood Reporter. “I finished it feeling maybe I didn’t love filmmaking anymore, which was frightening. I spent all my life wanting to make movies and the last decades of my life making them. But do I still love it?”

Clooney (left) and Baumbach on location in Tuscany, where Clooney’s character, movie star Jay Kelly, is set to receive a lifetime achievement award. The film shot in Los Angeles, London, Paris and Italy.

Rob Harris/Netflix

Says Adam Sandler (right, with Clooney): George and I both know the feeling of what Jay Kelly was going through, considering his entire career, the choices that he makes and the pain it can cause,” says Adam Sandler. “We both identified with the subject matter, as we both know what it’s like to go away and make a movie. Life shuts down around you, and it’s all about the movie.”

Peter Mountain/Netflix

It was 2023’s Barbie that pulled him back. Co-writing the script with his wife, Greta Gerwig, and watching her direct with visible joy rekindled something fundamental. “Greta has always influenced me,” Baumbach says, “but watching her on that film reminded me of how I’d felt earlier in my career. That absolutely influenced how I approached Jay Kelly.”

Baumbach developed the script with Emily Mortimer, with whom he had grown close on White Noise, where Mortimer jokingly describes herself as “playing stage mother” to her actor children, Sam and May Nivola.

“It started by him saying he wanted to make a film about a movie star who kind of runs away from his own life and goes a bit mad,” Mortimer says. “And he wanted it to be on a train.”

From the beginning, they knew the role demanded a genuine movie star.

“The audience needed to feel the same history with the character that the people in the movie do,” Baumbach says. “It wouldn’t have worked otherwise. George is perfect because there’s something timeless about him. He could have been a movie star in any era.”

When Clooney read the script, he told Baumbach: “You wrote yourself into a corner. Only about three people can play this part.”

Adds producer David Heyman, “There aren’t many people like George, with that body of work and that kind of star power.”

Baumbach and Mortimer lace Jay Kelly with insider jokes. There’s a running gag about a piece of cheesecake that keeps appearing in Jay’s rider. Clooney recognized it instantly.

“I’ve certainly been in that position where, because you liked something once, somebody put it in your rider,” he says. “For me, it was Fuji apples. Every time I walk in a room, there are Fuji apples.”

Still, both Baumbach and Clooney insist that Jay Kelly is not a self-portrait.

“I recognize Jay Kelly,” Clooney says. “I’ve known people like that — not just in my industry — who aimed for their career well over the balance of their family.” He recalls his aunt Rosemary Clooney later regretting what she missed. But he draws a clear distinction: “I had it easier. I didn’t get my career going until I was in my mid-30s. I’d already failed at things. When success hit, I was in a much better position to deal with it.”

For Jay’s agent, Ron, Baumbach wrote with Adam Sandler in mind, drawing on their collaboration on 2017’s The Meyerowitz Stories and the friendship that followed.

“He’s playing the manager, not the movie star,” Baumbach says. “But Ron shares so many of the qualities of the Adam I know: warm, generous, loyal, devoted. And he works harder than anyone. It’s a way for Adam to play himself in disguise.”

Adds Sandler: “I know many Rons. I’ve met a lot of people over the years who put parts of their own lives aside to make sure mine ran smoothly.”

Formally, Baumbach wanted the film to feel old school. Shot on celluloid with minimal CGI, Jay Kelly relies on practical, in-camera effects wherever possible.

That philosophy announces itself immediately. The opening shot is a 12-page oner that begins with a Sylvia Plath quote — “It’s a hell of a responsibility to be yourself. It’s much easier to be somebody else, or nobody at all” — painted in black on glass, revealed as smoke drifts past. The camera glides through a chaotic film set, a crime drama where everyone is prepping the final scene. “We’re coming to the end,” says an old hand working the fog machine. The camera whizzes past a dozen characters before landing on leading man Jay Kelly. “I don’t want to be here anymore,” gasps Clooney as Jay, slumped on the ground and bleeding from a bullet wound. “I want to leave this party.”

The director yells cut. Jay: “Can we go again? I’d like another one.”

Notes Baumbach: “It’s not stitched together. “Even the Plath quote was practical. Then we rack focus through the glass.”

Cinematographer Linus Sandgren approached the shot like choreography. “It was similar to what Damien Chazelle and I did on [2016’s] La La Land,” he says. “Building it piece by piece.”

Adds production designer Mark Tildesley: “As the camera moves, it’s all disjointed. You see these painted flats, all the artificiality. Then the camera comes around, and everything comes into frame, snaps into focus.”

Throughout Jay Kelly, Baumbach employs those practical, in-camera effects. For the train ride Jay takes to Italy, the production found a classic romantic model, the Arlecchino, a 1960s Italian train designed for the Rome Olympics. Tildesley studied the original in a Milan museum and rebuilt a section onstage at Shepperton Studios, with exterior plates filmed along the real Milan-to-Tuscany route.

The train car was cut off at both ends, allowing Sandgren to mount a long crane with a remote-head camera and long, thin lens that could “swim” through the carriage, people passing back and forth in front of the lens. The mechanics are elaborate, but the effect is simple: Jay is always in motion, rarely at rest.

Baumbach applies the same practical logic to Jay’s memories, which interrupt the present without warning. Sets from Jay’s past were bolted onto contemporary locations. A curtain parts on a private plane, revealing an acting class from 30 years earlier. Jay is staring at his reflection in the mirror of the train bathroom. He turns around and finds himself in the child care center where his daughter Jessica works.

“He’s looking in the mirror on the train, and when he looks outside, the camera pans,” says Heyman. “At that moment, George ducks down, the crew remove the mirror and he jumps back up on the other side.”

Continues Sandgren: “The camera pans back, and now he’s playing his own reflection. He turns right and sees Jessica in the memory of the classroom, which is the other set. We push in, and he ducks down. He’s got this Velcro-ed shirt that an assistant rips off. He walks right into frame again with a completely different costume, the one from the past.”

Baumbach and co-writer Emily Mortimer became close during the shooting of White Noise, on which her kids had small roles. “It was a kind of reverse nepotism,” she quips. “My kids got me the job.”

Peter Mountain/Netflix

The Italian train was a set built on a stage in London on a movable platform, with LED screens outside the windows showing the actual journey south. “When you were on it, the train rocking, and the landscape moving by,” says Baumbach, “you believe you’re on a trip to Tuscany.”

Peter Mountain/Netflix

For those memory sequences, Nicholas Britell’s score shifts direction. His “happy/sad” theme — recorded on analog tape to evoke classic Hollywood scores — is played in reverse.

“I didn’t just reverse the audio,” Britell says. “I wrote the theme backwards and played it that way. It ended up being very evocative, hypnotic.”

That inward quality runs through the performances of the characters whom Jay encounters along the way — figures who drift briefly into his orbit before disappearing again. Patrick Wilson plays Ben, another of Ron’s clients, who’s a successful star, albeit not on a Jay Kelly level. “He’s sort of the absurd version of me. Certainly, I’m less famous than George Clooney,” Wilson quips. “So that part rings true.” Wilson says he never read the full script. When Ben turns up in Jay’s story, he has literally no idea what the man is going through.

“It was the only time I’ve ever done that in my career, where I haven’t read the script of a film that I was doing,” says Wilson, “but I think it was just Noah’s way of showing that Ben is just in his own world, on his own trajectory.”

Billy Crudup gives a devastating, one-scene bravura turn as Timothy, Jay’s old acting-school friend whose career stalled while Jay’s soared.

“Every actor is Timothy at some point,” Crudup says. “Your proximity to a completely different life is so close all the time.”

The scene, over drinks at Santa Monica dive bar Chez Jay’s, has Jay Kelly asking Timothy to “do that method thing” and deliver a devastating performance on cue.

“I said to Billy, ‘Are you a method actor?’ ” Clooney recalls. “And he’s like, ‘No.’ I go, ‘What are you gonna do, dude?’ He goes, ‘I have no idea.’ “

For the scene, Crudup decided to try the method. He practiced one of method acting’s tools, called sense memory. “It was about finding a traumatic memory in my past. I journaled about it a lot so I could call upon it immediately,” says Crudup. “And it works. The only problem with retraumatizing yourself is you don’t stop crying. I called my wife and said: ‘I could cry about anything now.’ “

“It’s my favorite scene in the film,” says editor Rachel Durance. “And it’s no trickery on my part. We just let it play.”

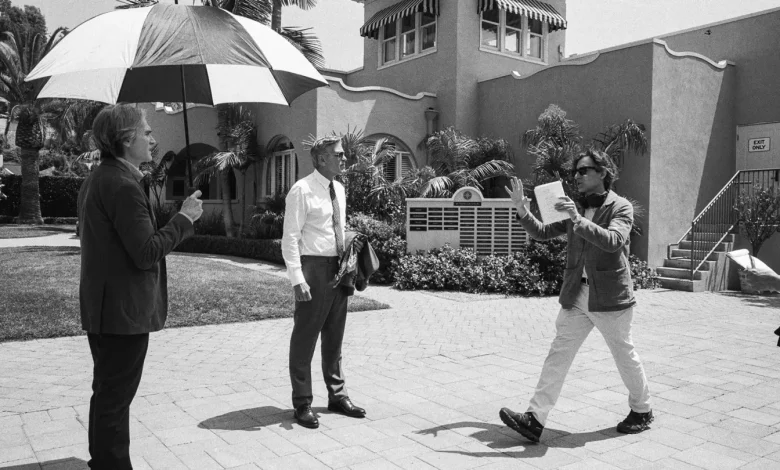

Baumbach blocks a scene with Clooney (left) and Crudup outside Santa Monica landmark Chez Jay’s.

Wilson Webb/Netflix

“When I wrote Ron, I was writing for Adam,” says Baumbach of Sandler’s character, Jay’s long-suffering agent, Ron Sukenick. “Ron shares Adam’s qualities: generosity, loyalty, family devotion.”

Peter Mountain/Netflix

Visually, Jay Kelly starts tightly focused on its protagonist. “The camera stays with him, he’s centered, everything revolves around him,” says Sandgren. “But slowly we pull back, bring other people into the frame, block his view, [and] he becomes part of the environment.”

Baumbach puts it this way: “He starts as a movie star, as an avatar for our dreams, and by the end, he’s one of us — a human being.”

Jay’s long run from himself ends with a climactic scene in a Tuscan forest. He has a phone call with Jessica, a wrenching Baumbach scene of brutal emotional honesty.

Jay admits he chose his career over being a good father. Jessica tells him he’s been a good movie star. “You make a lot of people happy.” But she’s not one of them. “I’m going to have a good life, Dad. Just not with you.”

“Man, that breaks my heart,” notes Sandler. “Such an amazing and heartbreaking scene.”

For editor Valerio Bonelli, the forest scene is the emotional core of the film. “There’s nothing fancy about it,” he says. “It’s rhythm, silence, restraint. I saw people crying watching that scene. That’s when you know it works.”

Britell’s score fractures here as well. The “happy/sad” theme that has propelled Jay forward is broken apart into something darker and more searching. “That piece came from experimenting with how far I could stretch the theme,” Britell says. “When Noah heard it, he immediately said, ‘This goes in the forest.’ It’s Jay’s dark night of the soul.”

After the forest, the movie has nowhere left to go but the thing Jay has been chasing as both alibi and destination: the Italian festival tribute. The ceremony returns him to the machinery that made him — velvet seats, programmed applause, a room full of people ready to celebrate the myth — but now Jay is no longer performing inside it. He’s watching it operate.

Baumbach says the tribute reel, cut from Clooney’s own filmography, was always scripted and that he didn’t show Clooney the footage until the moment they filmed it.

“He did a montage at the end with [clips] of my actual films, which threw me, I have to say. I thought they were just going to do greenscreen and come up with something,” explains Clooney. “I was always playing a guy filled with regret, and I’m not that guy. Then suddenly I’m watching my own career. I think the very first clip was, I’m coming up the elevator or something, a clip from Ocean’s 11. And I was like, ‘At least he didn’t use Batman & Robin.’ “

Durance, who helped assemble the reel, describes the decision not to show Clooney anything in advance as crucial. “He watched it, and we only used that take,” she says. “There was something raw about it. You’re watching a person watch himself for the first time.”

Sandgren shot the scene on a long lens, pushing slowly into Clooney’s face as the images played. “It was incredible to see his reaction,” he says. “Then the audience stands up in this crazy standing ovation. It became a real tribute reel for the audience.”

The moment wasn’t just Clooney’s. Sandgren caught Sandler breaking, too. “It was him and Adam,” he says. “Adam began to cry, and I caught the tear.” Baumbach wanted one detail — hands clutching in the dark — but the cinematographer stayed on the faces. “Noah was like: ‘Tilt down to the hands!’ ” Sandgren recalls. “But I didn’t, because I saw … he had a tear that was about to fall.”

As the lights come up and the audience explodes in applause, Jay looks straight at the lens: “Can we go again? I’d like another one.”

“The expression we used to describe the music was happy/sad,” says composer Nicholas Britell. “Noah was looking for this complex sort of emotion, of something for Jay that could feel at times propulsive but also at times introspective, that could both have a have a lightness but also a melancholy to it.”

Alejandro Chavez/Netflix

Britell recorded the score at Abbey Road and AIR studios in London, recording live to analog tape. “It’s like the equivalent of shooting on film,” he says. “It’s the sound of the recordings we all grew up loving.”

Alejandro Chavez/Netflix

Adds Britell: “In some places in the film, we wanted this old cinema sound, this sort of romantic, sweeping sound, with a huge orchestra, and every instrument you can imagine.”

Alejandro Chavez/Netflix

This story first appeared in a January stand-alone issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.