Canada’s LNG Mirage: Why Most Projects Won’t Be Built and Taxpayers Won’t See the Payoff

Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Canada is planning LNG export infrastructure as if global gas demand growth will persist for decades, but the energy system is moving in a different direction. Under conditions of sustained LNG oversupply, rapid global deployment of solar and batteries, and rising financing costs for fossil infrastructure, most proposed Canadian LNG capacity will not be built. Some of what is built will still become stranded. Public money already committed will not generate the economic returns politicians are promising, because the underlying demand assumptions no longer hold.

This analysis rests on a set of assumptions that are increasingly hard to dismiss. Global LNG markets are oversupplied today and remain oversupplied through the late 2020s based on projects already under construction. By 2026 and 2027, evidence of structural LNG demand decline in Asia becomes clear, not because of recession but because electricity systems are changing. Solar generation, paired with batteries, is expanding faster than forecast in most regions. This combination displaces gas directly in power generation and indirectly in industry by lowering wholesale electricity prices. By the early 2030s, LNG demand in Asia is no longer growing and is instead contracting. At the same time, financiers are raising the cost of capital for oil and gas projects and shifting capital toward renewables and grid infrastructure. Governments continue to support LNG with public funds even as private capital grows more cautious.

The global LNG supply glut is large and persistent. More than 150 million tons per year of LNG export capacity is already under construction worldwide, with expected commissioning concentrated between 2025 and 2029. This wave alone exceeds plausible demand growth under conservative scenarios. Additional projects have reached final investment decision but have not yet broken ground, adding further optional supply. Even if global LNG demand were to grow at rates seen in the 2010s, which current data no longer supports, this capacity would be sufficient to meet it. Canada is attempting to enter a market that is already full, with projects that are later in the queue and exposed to merchant risk.

LNG is increasingly the energy of last resort for importing countries and the most expensive way to generate electricity. It requires gas production, processing, long distance pipeline transmission, liquefaction, shipping, regasification, and local distribution. Each step adds cost and capital intensity. When solar and wind are available domestically, and batteries can shift energy across hours and increasingly across days, LNG sits at the top of the cost stack. It is dispatched when cheaper options are unavailable. That role can support reliability, but it does not support high utilization or stable long term demand.

Pakistan offers a recent and concrete example of this dynamic. In 2024, Pakistan installed roughly 17GW of new solar capacity, much of it behind the meter and outside central planning processes. This solar displaced gas fired generation during daylight hours and reduced overall gas demand. As a result, Pakistan found itself holding commitments for 24 LNG cargoes that it no longer needed. The country was forced to seek buyers for those cargoes on the international market, often at a loss. This was not the result of climate policy pressure. It was the outcome of households and businesses installing the cheapest available energy option.

China and India show the same pattern at much larger scale. China continues to install hundreds of GW of solar and wind per year, alongside rapid expansion of battery manufacturing and deployment. Gas plays a limited and shrinking role in China’s power sector, primarily for peaking and industrial feedstock. LNG import growth has not only stalled but shrank by double digits in 2025 despite good economic growth. India is accelerating solar deployment, expanding wind, and beginning to deploy grid scale batteries. LNG imports fluctuate with price, and structural growth is not only absent, but declined by double digits in 2025. In both countries, renewables are not supplementing gas. They are displacing it.

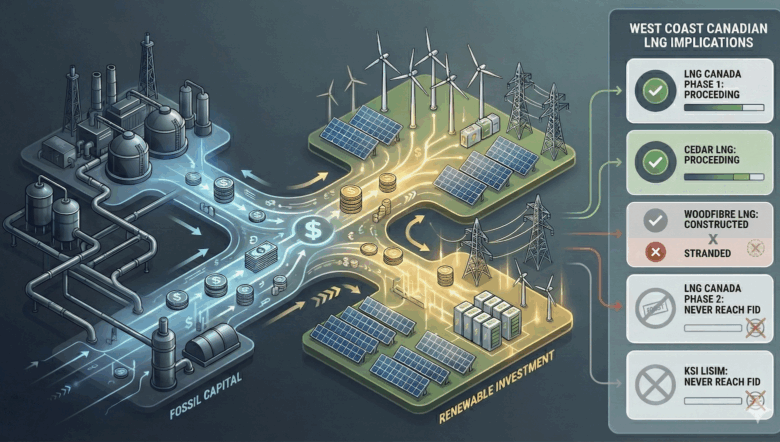

Against this backdrop, Canada has five LNG export proposals. LNG Canada Phase 1 in Kitimat has a nameplate capacity of 14 million tons per year and is owned by a consortium led by Shell, with Petronas, PetroChina, Mitsubishi, and KOGAS as partners. It is undergoing ramp up after being commissioned in 2025, and is expected to reach full capacity in 2026. LNG Canada Phase 2 is a proposed expansion of an additional 14 million tons per year. It has not reached final investment decision and remains optional.

Cedar LNG is a floating LNG facility proposed near Kitimat with capacity of about 3.3 million tons per year. It is a partnership between Pembina Pipeline and the Haisla Nation. It has reached final investment decision and targets commissioning around 2028. Woodfibre LNG near Squamish has capacity of about 2.1 million tons per year and is owned by Pacific Oil and Gas. It has reached final investment decision and is under construction, with commissioning targeted for 2027 or 2028. Ksi Lisims LNG near Prince Rupert is a proposed 12 million ton per year project led by Western LNG, a Houston-based single project firm backed by financiers close to President Trump, with projected commissioning in the early 2030s, but it has not reached final investment decision.

The cost of financing determines which LNG projects move forward and which stall, and it has changed materially from the last decade. Before final investment decision, LNG developers now face equity return requirements in the 15–20% range, up from roughly 10–12% that was typical in the early 2010s. Project finance debt that once priced at 150–250 basis points over benchmark rates with tenors of 15–20 years is now more likely to require spreads of 300–450 basis points with shorter tenors and stricter coverage ratios, if it is available at all. Once projects enter operation, refinancing no longer assumes stable long-term utilization. Lenders increasingly model declining throughput and lower terminal value, which raises effective operating-phase capital costs into the 9–13% range for LNG assets that would previously have been treated as quasi-infrastructure. By contrast, utility-scale renewables typically clear with equity returns of 6–9% and long-tenor debt at much tighter spreads, reflecting lower demand risk and more predictable cash flows. Capital is not responding to policy pressure or narrative framing. It is reallocating based on expected risk-adjusted returns.

Likely outcomes for the five Canadian LNG proposals by author.

For projects that have not reached final investment decision, higher cost of capital is often fatal. Ksi Lisims LNG is a large greenfield project with partial offtake and no operating assets. Under conditions of oversupply and declining demand, it cannot secure financing at terms that make economic sense. Its probability of reaching final investment decision falls to single digits. LNG Canada Phase 2 is different in structure but similar in outcome. Its sponsors are large integrated firms that could self finance, but they face opportunity cost. Doubling capacity into a declining market does not compete well against investments in renewables, grids, or shareholder returns. Phase 2 is likely deferred indefinitely and never built.

Projects that have already reached final investment decision tend to proceed through construction because capital is sunk. LNG Canada Phase 1 will be completed and operate into the 2030s. Cedar LNG and Woodfibre LNG are also likely to complete construction. Completion does not imply long term success. It means the decision point has passed.

Likely million tons per annum (MTPA) volumes across the projects by author.

In the early 2030s, these three facilities briefly represent about 19.4 million tons per year of Canadian LNG export capacity at full operation, equivalent to roughly 2.5 Bcf per day of gas demand. This level is reached only if all three run at nameplate capacity. That peak, if it occurs at all is short lived. As global LNG demand declines and prices remain under pressure, utilization falls. By the mid 2030s, LNG Canada Phase 1 may operate at around 75% utilization, Cedar at about 65%, and Woodfibre at about 50%. Total effective exports fall to roughly 13.7 million tons per year, or about 1.8 Bcf per day.

By 2040, Woodfibre LNG faces a high risk of physical stranding. Its small scale, high fixed costs, urban location, and exposure to refinancing risk make continued operation difficult under low utilization. In this scenario, Woodfibre is mothballed. LNG Canada Phase 1 continues operating at around 70% utilization, delivering about 9.8 million tons per year. Cedar LNG operates opportunistically at around 60% utilization, delivering about 2.0 million tons per year. Total Canadian LNG exports fall to about 11.8 million tons per year, or roughly 1.55 Bcf per day.

To be clear, the world of energy globally will be so radically different by 2040 that all three Canadian LNG plants face a clear risk of both fiscal and physical stranding. The scenario I’m outlining is conservative, not radical. This is modern energy reality with clear trends.

The implications upstream are significant. Western Canadian gas production has long been constrained by getting it to markets. LNG was framed as the solution that would unlock decades of drilling. Under this scenario, coastal LNG demand peaks briefly and then declines. The base Coastal GasLink pipeline capacity of about 2.1 Bcf per day remains useful, but any expansion toward 5 Bcf per day becomes unjustifiable and is not financed. Dedicated infrastructure built to serve Woodfibre becomes underutilized or stranded.

Within Alberta and northeastern British Columbia, the result is increased volatility rather than sustained growth. Core Montney production remains viable due to low costs, but higher cost plays face economic stranding. Transmission systems experience lower throughput over time, raising per unit tolls. Higher tolls reduce netbacks, which reduces drilling, which further lowers throughput. This feedback loop leads to fiscal stranding of assets that are still physically present.

Public money is deeply embedded in this system. The federal government has provided about $275 million in direct support for LNG Canada Phase 1. Cedar LNG has received about $200 million in federal funding and $200 million from British Columbia, alongside hundreds of millions in loans from Export Development Canada. Coastal GasLink has benefited from Crown financing. Woodfibre’s supporting pipeline infrastructure is being built by a regulated utility, with costs recovered from ratepayers over decades.

These commitments do not disappear when utilization falls. Grants are spent regardless of outcomes. Loans carry credit risk that becomes political if projects underperform. Regulated utility assets are paid for through rates even if throughput declines. This is how long term taxpayer and ratepayer burdens emerge, not through outright nationalization, but through socialized costs and shortened asset lives.

Western Canada already has a fossil fuel pipeline, the Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX), that we are paying $2.5 to $3 billion a year in effective oil subsidies for because the costs ballooned and oil companies are paying pre-contracted, low rates per barrel. That should weigh heavily in discussions in political circles about exposing Canadian ratepayers to more structural, long lasting money for the oil and gas industry.

Politicians often justify these investments on the basis of jobs, revenues, and energy security. Under the assumptions laid out here, those benefits are far smaller than advertised. Fewer projects are built. Those that operate do so at lower utilization. Asset lives shorten. Royalty and tax flows are weaker. Meanwhile, public capital could have been deployed into energy systems that are growing rather than shrinking.

The federal Major Projects Office, established under Mark Carney’s guidance to accelerate projects deemed strategically important, highlights a growing disconnect between political prioritization and market reality. LNG Canada Phase 2 and Ksi Lisims LNG have both been placed on the Major Projects Office list, signaling federal intent to fast-track approvals and coordinate permitting. Cedar LNG has also received strong federal attention and direct funding, even if it sits in a different category as a smaller Indigenous-partnered project. Woodfibre LNG, by contrast, is not part of the Major Projects Office framework and has proceeded largely through provincial and regulatory channels.

The mismatch is striking. The projects most prominently elevated by the Major Projects Office are precisely those least likely to reach final investment decision or operate at meaningful utilization under conditions of LNG oversupply, declining Asian demand, and rising cost of capital. Meanwhile, the projects most likely to operate into the 2030s are either already sanctioned or too small to feature centrally in federal industrial strategy. The Major Projects Office is optimizing for speed and symbolism, but markets are optimizing for risk and return, and those two filters are increasingly selecting different outcomes.

Canada is not alone in facing this mismatch between fossil infrastructure planning and energy system reality. The difference is that Canada is committing public money late in the cycle. LNG export terminals and pipelines are long lived assets. Solar, wind, and batteries are being deployed faster than those assets can pay back. Planning based on past demand trends leads to stranded capacity and stranded public investment.

The upside of all of this, minor though the silver lining will be, is that far less Canadian LNG will be shipped each year than current heady dreams suggest, reducing significantly the climate damage that our products cause globally. It’s still billions of tons of CO2e over the lifespan of these projects from our product with federal backing, in an era when the International Court of Justice has made it clear that the liability buck stops with the government, not the firms.

The conclusion is not that gas disappears overnight. It is that LNG becomes a declining, capital constrained business much sooner than project timelines assume. Most proposed capacity is never built. Some built capacity becomes stranded. Public money does not earn the returns promised. The gap between political expectations and economic outcomes widens, not because of ideology, but because the energy system changed direction while infrastructure planning did not.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Advertisement

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy