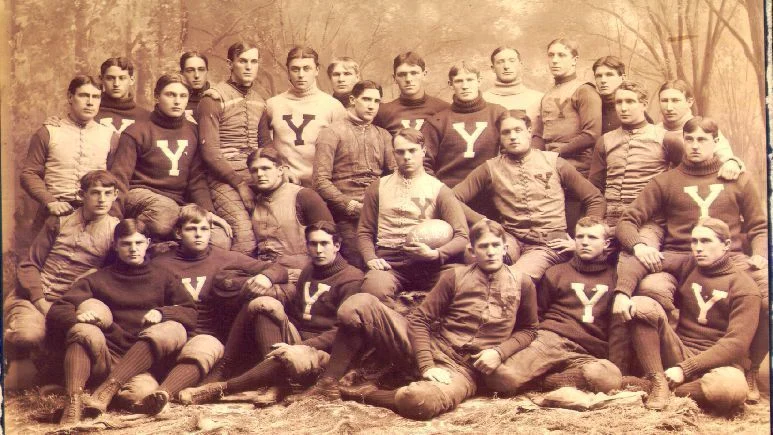

Meet the 1894 Yale Bulldogs, the first college football team to go 16-0

On Monday, Indiana will look to cap off a dominant storybook season in the national championship game, where a title game win will give the Hoosiers a 16-0 record that’s without parallel in the modern major college football era. (North Dakota State has also put together a 16-0 season, but at the FCS level.)

But it’s not without parallel entirely, thanks to the 1894 Yale Bulldogs.

Editor’s Picks

1 Related

Facing a schedule stuffed with both recognizable Ivy League rivals and an eclectic mix of other foes, collegiate or otherwise, the 1894 Bulldogs racked up 16 wins of their own without a loss, finishing the season with an aggregate scoreline of Yale 485, Opponents 13.

The Bulldogs’ squad was packed with talent — seven of the 11 projected starters in an official “game souvenir” (something like a game program in the form of a bound flipbook) from the team’s matchup against Harvard would earn All-America honors at some point in their careers — but admittedly the sport they played was a far cry from what fans today might recognize.

So who was this remarkable 1894 Yale team that Indiana might join Monday night? Here’s everything you need to know about the winningest squad you’ve (probably) never heard of.

So just how did Yale go 16-0 with any form of playoff system — or postseason period — still decades away?

Without much in the way of regulation, the Bulldogs (and other teams of their era) were free to design their schedules however they saw fit. Schedules across teams were uneven. Just because Yale played 16 games in 1894, that didn’t mean everyone was doing the same. Harvard, for instance, played 13 games that season. Princeton played 10. Brown — which Yale actually played twice, at home in early October and on the road in early November — played 15 (including “doubleheader” series with Harvard and MIT in addition to Yale). With a smaller number of teams on the West Coast, USC played only once!

“We use the term nowadays that college football is in the Wild West because there’s so little rules about NIL and [the] transfer portal, but what’s ironic is in the 1890s it was also very much Wild West in that there was no uniformity to scheduling,” said Denis Crawford, a historian and exhibit designer at the College Football Hall of Fame. “Teams could schedule however many games they wanted. They could play every two or three days.”

The Bulldogs had also cultivated a team that had the commitment and manpower, as well as sufficient opponent interest, to put together and shoulder the load of a 16-game season. One of the sport’s forefathers, Walter Camp, had begun coaching at Stanford by 1894, but Camp was a longtime figure in New Haven and his fingerprints were all over Yale’s programwide build.

“It’s more akin to when Bill Walsh retired as head coach of the 49ers after the ’88 season, they won the Super Bowl, George Seifert takes over, they win the Super Bowl the next season. Now, that’s George Seifert’s Super Bowl, but Bill Walsh’s fingerprints were all over it,” Crawford said. “I think you give Camp credit for developing that level of competence, that level of excellence that everybody wanted to try to compare themselves against. And the only way to compare yourselves against them is to schedule them.”

As for how Yale was able to stuff 16 games into a single fall, a couple of important elements were at play. There were the two separate matchups against Brown (which, in fairness, actually isn’t without recent antecedent thanks to Oregon State and Washington State’s series this season). The Bulldogs also packed their calendar, playing two games a week (one on Wednesday and one on Saturday) from the end of September until the middle of November.

There was also the the fact that Yale didn’t exclusively play fellow universities.

Their opponents weren’t all colleges?

No, they weren’t, but this wasn’t a scandal of any sort. Five of the Bulldogs’ games were against “athletic clubs,” a schedule-filling practice not uncommon for the time. Orange Athletic Club, for instance, played Yale, Harvard, Princeton and Brown. Boston Athletic Association was another Bulldogs opponent that fall, which also played games against the likes of Harvard, Brown and MIT.

So who were these athletic clubs? They were teams made up of members at local social clubs for men, including former college football players now beginning their nonathletic careers in assorted cities.

“They [were] where young men of appropriate social class spent their evenings and hung out, all that kind of stuff,” said Michael Oriard, a sports historian whose most recent book, “Sanctioned Savagery: A History of Violence in Football,” was published in September. “And so the athletic clubs would have players who had played at Harvard, Yale and Princeton … in the New York area … and they were now launching their careers in law or business or whatever. And [they] would play for the athletic club.

After all, who was going to tell the universities that they couldn’t schedule these clubs, anyway?

“There were no conferences,” Oriard said. “There was no NCAA. Schools did what they wanted to do.”

Hold on, let’s back up some. What did football even look like in the 19th century?

A series of adjectives might do the job best: Brutal. Chaotic. Dangerous. Still-evolving.

“It was just the most brutal form of Red Rover,” Crawford said.

At the time of Yale’s 16-0 season, football was still very much actively in the process of shedding the lingering aspects of the sport’s rugby origins. The forward pass? Forget about it, that was still more than a decade away from its 1906 legalization. The alignment of teams would see seven players facing off on the line of scrimmage (two ends, two tackles, two guards and a center), the quarterback under center and three players (two halfbacks and a fullback) behind the quarterback. This was the tail end of the “mass momentum” plays era — a chaotic mess that included multiple players on both teams moving toward the line before the snap.

What’s Trending in the CFP?

• Miami-Indiana average ticket price trending toward most expensive ever for CFB

• City of Bloomington unofficially names pond in D’Angelo Ponds’ honor

• Miami looking to become latest team to win ‘home’ national title game

• How Indiana lost, remembered, and revived its 50-year-old bison mascot

• Why Miami’s Columbus High School can’t lose the CFP title game

“So the game in 1894 was this kind: You have these players moving toward the line before the balls snap, but you can only have three of them,” said Oriard. The three-player limit had recently been put into place in an effort to ban flying wedge-style plays, one of the sport’s particularly dangerous early elements.

“But it’s still, you know, just this massive chaos, flailing of arms and all that kind of stuff on every play,” he said.

Accordingly, the physical sport was also a rather dangerous one. One contemporary survey of 187 former college football players saw just under 150 total injuries reported, with 39 reported permanent injuries of some form. The New York Times reportedly found that 26 players had died in the 1892 season.

In a game that saw an impressive amount of close quarters contact, there was at least one extremely prominent rule: no slugging. But the still-growing rule book — there had been some progress made, curtailing the flying wedge and adding a fair catch signal were among steps forward made prior to the 1894 campaign — was not always enforced with vigor, and there was plenty of grey area.

“There’s just a lot of pushing and shoving and elbowing, pushing your shoulder in, but your shoulder isn’t protected — lots of broken collarbones in these years and all that,” Oriard said. “And your head is barely protected. It’s interesting that the first piece of equipment they came up with was this rubber nose guard. It’s really a weird-looking contraption, but, you know, lots of broken noses.”

Few games encapsulated the sport’s bloody nature like Yale’s rivalry showdown with Harvard that season. A number of players for both teams were forced off the field with all sorts of injuries, with multiple players being hospitalized. The Hartford Courant reported the game to be “the roughest and fiercest game that has ever played on Hampden Park,” adding “although two men were disqualified for roughness, there was much slugging that the umpire ‘did not see.'”

The New York Times went another direction with its assessment: “An ordinary rebellion in the South American or Central American States is as child’s play compared with the destructiveness of a day’s game.”

So just how good were these guys? Who were the best players?

We don’t exactly have game film to analyze, but by all accounts Yale’s roster was absolutely stacked.

Of the 10 All-Americans named by Harper’s Weekly writer Caspar Whitney that season, five were Bulldogs (it does bear noting that Whitney’s selections were made in association with none other than Camp, the Yale legend). One of those five was captain and left end Frank Hinkey, for whom 1894 marked a fourth consecutive season of All-American honors. Hinkey was one of three members of the 1894 Yale squad to end up in the College Football Hall of Fame, joined by right guard Bill Hickok and left halfback Sam Thorne. Of the 11 players in the Bulldogs’ starting lineup, seven earned All-American honors at some point in their careers. Four earned such a nod in multiple seasons.

And while game footage may be lacking, complimentary newspaper accounts of Yale’s star players’ talents are not. The Philadelphia Enquirer said of Hinkey’s all-around — and extremely physical — game after the Harvard win: “He seemed to be everywhere at the same time, and although his play was rough, and sometimes almost brutal, it was winning football just the same.”

Said the Boston Globe of Thorne following the Bulldogs’ win over Dartmouth: “His dashes were remarkable, and once underway it was well-nigh impossible to stop him. But his kicking goals from the field against the wind was the star feature of the day.”

Ahead of Yale’s final game of the season against Princeton, the Pittsburgh Press compared fullback Frank Butterworth, another Bulldog All-American, to a pair of Tiger opponents as such: “Butterworth at fullback on the Yale team is better in every way than [W.H.] Bannard or [Garrett] Cochran, if the latter should be able to play. Butterworth kicks better, runs into the line better and stands on his feet — this last, though not only better than either Bannard or Cochran, but better than any other man on the field this year.”

Accordingly, Yale didn’t just win 16 straight games — it stomped through 16 straight games. The Bulldogs were scored upon in only three of their games, allowing just 13 total points all season.

A poster from the Yale-Princeton game at the end of the 1894 season. The Bulldogs beat the Tiger 24-0 for their sixteenth and final win of the campaign. Photo 12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

That sounds plenty impressive for the time period, but how do they stack up compared to this year’s Indiana squad? Or all time?

We’ll let our own Bill Connelly analyze this one:

At first glance, there’s plenty of reason to be impressed with Yale’s 1894 squad. The Bulldogs played Saturdays and Wednesdays for basically two months, traveling without much convenience and replenishing themselves mostly with mutton and milk. They were led by a head coach who was barely older than they were — Williams Rhodes, an 1890 All-American, was just 25 — and there was evidently enough wear-and-tear involved that the school never attempted that many games again (though they still played 15 in 1895 and 14 in 1896). To go through a 16-game grind with almost no scares (only two games were decided by single digits) and a season-ending 485-13 scoring margin certainly seems pretty ridiculous.

It was only so-so for the dominant program of the day, however. Yale’s SP+ percentile rating for 1894 was 98.3% — comfortably the best in the country but more in line with, say, 1958 LSU or 2023 Oregon (also members of the 98.3% club) than the greatest teams ever. Their strength of schedule, after all, wasn’t amazing.

The idea of “major schools” was pretty loose then, but among the teams that played a solid amount of games against other major-ish schools, there were about 13 teams we can conclude were pretty good. Yale played four of them a total of five times; The Bulldogs beat No. 3 Harvard 12-4, No. 4 Princeton 24-0, No. 10 Brown twice by scores of 28-0 and 12-0 and No. 13 Army 12-5. That’s an average scoring margin of plus-15.8. Against 11 other teams that were either local athletic clubs or just not very good, they won by an average of 35.7. That includes a 67-0 win over Tufts, wins of 50-0 and 34-0 over Lehigh and 48-0 over the Chicago Athletic Club.

Sure, Indiana has been able to rack up the stats against lesser teams like Indiana State (73-0), UCLA (56-6), Purdue (56-3) and Kennesaw State (56-9). But the Hoosiers have also beaten seven current SP+ top-25 teams by an average of 20.4 points. Their current SP+ percentile rating is 99.4%, a rating shared by celebrated teams like 2022 Georgia, 2001 Miami and 2008 Florida. Granted, 1983 Nebraska also boasts that percentile rating, and the Huskers still managed to lose a de facto national title game to a Miami team playing in its home stadium. But if the Hoosiers reach 16-0, they’ll have done so in a far more impressive fashion than our Ivy League friends managed 131 years ago. — Bill Connelly

What happened to the Bulldogs after their incredible 1894 season?

Despite the departure of a pair of future Hall of Famers in Hinkey and Hickok after the season, there wasn’t much in the way of an immediate fall from grace for Yale. In fact, though the Bulldogs did record a pair of ties the ensuing fall, it would take until November 1896 for a team to beat them outright, when Princeton earned a 24-6 victory.

Impressive seasons continued to be the standard for the Bulldogs, who would boast nine national championships — either claimed, shared or outright — over the next decade and a half. But in the background, changes were brewing. The sport continued to evolve and more schools around the country began to develop their programs. The advantages Yale and its peers in the sport’s early adoption had built up slowly began to erode. In time, one of the sport’s first premier programs began to fade back toward the rest of the pack.

“Once the NCAA is formed in 1906, then Harvard, Yale and Princeton are no longer literally running the show, dominating. … The rules committees used to be a handful of Northeastern universities dominated by Harvard, Yale and Princeton. And particularly by Yale, and then Harvard in rivalry with Yale,” Oriard said. “As football powers, I would say that that’s pretty much gone before the 1920s.”

“[Football] started to spread throughout the country. … So you’re starting to get more and more young athletic men across the country playing the game,” Crawford said. “I think the change of the rules in 1906, which made the sport not completely safe but significantly safer than what it had been, brought more people to the game. And so when you increase the population of players and teams and coaches, you dilute power from the original group.”

Next year will mark the 100-year anniversary of Yale football’s last national championship, in 1927.