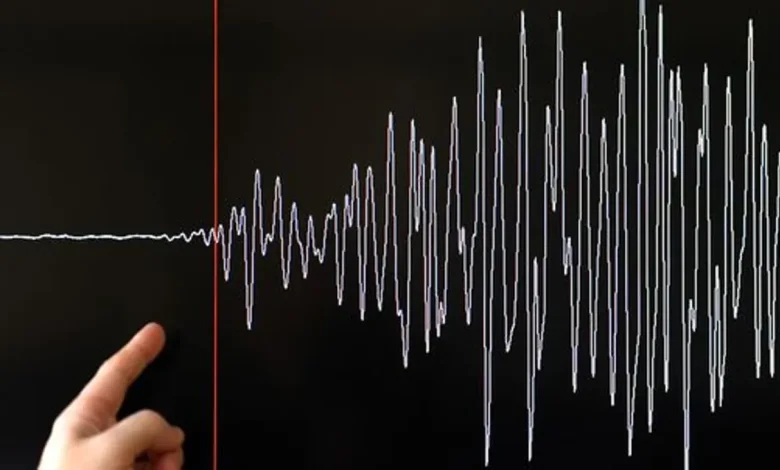

4.9 earthquake near Indio Hills; heavy shaking in Coachella Valley

Why do earthquakes happen? And how do we stay safe?

Here’s a brief explainer on how earthquakes begin, the worst quakes in California history and how to stay safe if one hits your town.

(This story was updated with new information.)

The U.S. Geological Survey reported a magnitude 4.9 earthquake about 12 miles northeast of Indio that caused serious shaking in many parts of the Coachella Valley on Monday, Jan. 19.

The quake struck at around 5:56 p.m. Five smaller aftershocks in approximately the same area followed over the next hour, with magnitudes between 2.9 and 3.5, USGS reported. Another five hit over the next six hours, with magnitudes between 3.2 and 3.7.

Aftershocks continued into the morning of Tuesday, Jan. 20. At 10:48 a.m., USGS reported a magnitude 3.6 earthquake about 11 miles north of Indio.

Because of the way earthquakes are measured, a magnitude 4.9 earthquake, like Monday evening’s, is far stronger than one under magnitude 4, like the aftershocks. The strength of a quake increases logarithmically with each digit up to 10. That means each whole number difference is a tenfold increase in measured amplitude, according to USGS.

There were no immediate reports of damage in Palm Springs, according to Palm Springs Police Department spokesman Gustavo Araiza. An Indio city spokesperson, Jessica Mediano, said the city had “no reports of injuries and no immediate reports of any visible road damage.” Initial reports online did not immediately show damage to other cities in the Coachella Valley.

ShakeAlert system sends earthquake alerts to cell phones

The USGS’s emergency alert system sent messages to phones for miles around the epicenter of the quake just as shaking could be felt. The warning told recipients to take cover and hold until the earthquake passed.

ShakeAlert, as the system is known, is a public service that can reach 50 million people on the West Coast of the United States. It is supposed to reduce the impact of earthquakes by giving people some warning before the shaking reaches them.

What am I supposed to do during an earthquake?

It depends on where you are.

Here’s what to do in the following situations, according to Ready.gov:

- Turn face down and cover your head and neck with a pillow if you’re in bed.

- If you are outside, stay outdoors and away from buildings.

- If you are inside, stay. Avoid doorways and do not run outside.

To protect yourself during an earthquake, drop down to your hands and knees and hold onto something sturdy. Cover your head and neck with your arms and crawl underneath a sturdy table or desk to shelter. If that’s not available to you, then crawl next to an interior wall to get away from windows. If you are under a table or desk, hold onto it with one hand so that if it moves, you can move with it.

What if I’m driving during an earthquake?

Slow down and pull over as soon as it’s safe, according to the California Highway Patrol. Remain in the vehicle with your seat belt fastened, engine off, and parking brake set. Once the shaking stops, check your vehicle for damage and its occupants for injuries. Only begin driving when it is safe to do so. Once you can start moving again, do so slowly and cautiously, avoiding any areas of the road that appear to be damaged or obstructed, and continue to avoid bridges and ramps.

Why do earthquakes happen?

The Earth has four layers: the inner core, outer core, mantle, and crust. The crust and top of the mantle make up another area called the “lithosphere,” which acts like a skin surrounding the Earth’s surface, USA TODAY reported.

The lithosphere, however, is not in one piece and exists like a puzzle or series of fragments, according to the United States Geological Survey. These parts of the lithosphere are not stationary and move slowly. These are called “tectonic plates.”

As the tectonic plates move and shift past one another, they occasionally bump or collide. This places stress on the plates’ edges. When the stress becomes too great, it creates cracks called “faults.” The point where these faults move against each other is called the “fault line.”

When there is too much friction between the fault lines, energy is suddenly released, triggering seismic waves that lead to an earthquake.

What have been the biggest earthquakes in recorded California history?

California’s largest recorded earthquakes since 1800, ranked by magnitude, according to the California Department of Conservation.

- 7.9: Jan. 9, 1857 in Fort Tejon Two killed; created 220-mile surface scar

- 7.8: April 18, 1906 in San Francisco Possibly 3,000 killed; 225,000 displaced

- 7.4: March 26, 1872 in Owens Valley. 27 killed; three aftershocks of magnitude >6

- 7.4: Nov. 8, 1980 just west of Eureka Injured 6; $2 million in damage

- 7.3: July 21, 1952 in Kern County 12 killed; included three magnitude 6-plus aftershocks in five days

- 7.3: June 28, 1992 in Landers. One killed; 400 injured; $9.1 million in damage

- 7.2: Jan. 22, 1923 in Mendocino. Damaged homes in several towns

- 7.2: April 25, 1992 in Cape Mendocino. 356 injuries; $48.3 million in damage

- 7.1: Nov. 4, 1927 southwest of Lompoc. No major injuries, slight damage in two counties

- 7.1 : Oct. 16, 1999 in Ludlow. Minimal damage due to remote location

When is the next earthquake in California?

It is not currently possible to predict an earthquake, though USGS scientists can calculate “the probability that a significant earthquake will occur in a specific area within a certain number of years,” according to USGS.

While earthquake forecasts and probabilities can be determined, USGS says those reports are “comparable to climate probabilities and weather forecasts” and not the same as predictions.

A USGS map of America reveals that portions of California face a greater than 95% chance of experiencing a slight or greater damaging earthquake shaking in 100 years. In other words, a strong earthquake on the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale that will be “felt by all” will move some heavy furniture and cause slight damage.

No, California will not ‘fall into the ocean’ due to earthquakes

Several hours before Monday’s earthquake, the Seismology Laboratory at Berkeley had posted an informational thread on California and earthquakes, saying it’s fiction that California could eventually break off and fall into the ocean.

“That’s because earthquakes in California cause horizontal motion, not giant sinkholes or land dropping into the sea,” the lab shared on X. “No part of California is sitting on an “edge” that can suddenly break off,” the lab said.

That means the state won’t detach, sink or disappear into the Pacific. Earthquakes will continue the lab stated, and the coastline will slowly shift over millions of years, “but the land isn’t going anywhere suddenly.”

Paris Barraza and Dinah Voyles Pulver of USA Today contributed to this report.