Lessons From My Me Too

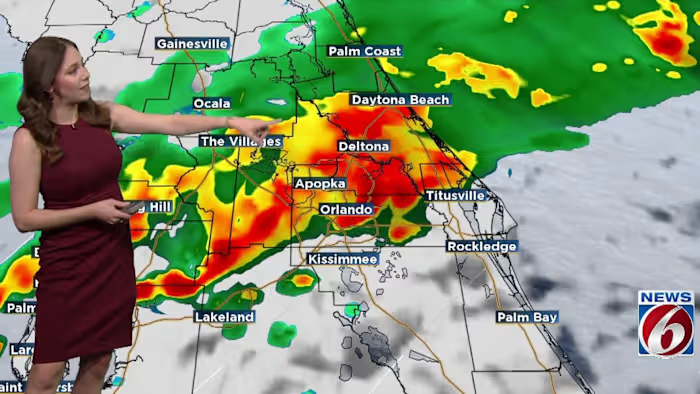

Brooke Nevils at the 2014 Sochi Olympics.

Photo: Courtesy of the author

My first thought when I woke up, underwear and the sheet beneath me caked with blood, was, This must have been a misunderstanding.

It was the only acceptable conclusion I could reach without my whole life falling apart. I was an NBC talent assistant at the 2014 Sochi Olympics, and the night before had been a blur but not an incomprehensible one. My longtime boss and mentor, Meredith Vieira, had just become the first woman in history to anchor prime-time Olympic coverage solo, and we’d met for a glass of wine in our hotel bar to celebrate. We’d been there for a while when her former Today co-anchor, Matt Lauer, happened to walk in. We waved him over, and I patted the seat next to me for him to join us. Nothing would ever be the same again.

Despite the rounds of vodka shots, the overwhelming power differential, and the bloody underwear and sheets, I would never have used the word “rape” to describe what had happened. Even now, I hear “rape” and think of masked strangers in dark alleys. Back then, I had no idea what to call what happened other than weird and humiliating. But then there was the pain, which was undeniable. It hurt to walk. It hurt to sit. It hurt to remember.

One strikingly clear thought crossed my mind and then was instantly struck from my consciousness: If anyone else had done this to me, I would have gone to the police.

But it was an utterly useless thought to have, if only because I knew that I would never, ever, have let anyone else do that to me and because I was in freaking Russia. Who would I call? Putin? The KGB? There was only NBC, and Matt Lauer was Today’s longest-serving anchor with the biggest contract in the 60-year history of morning television, worth a reported $25 million a year. In the news business back then, his point of view was reality, and if you disagreed with it, you were wrong. The whole thing had to have been my fault. I had given him the wrong idea, failed to be clear, failed to convince him, failed to stop him, failed to find a graceful way out of the situation without embarrassing him. I certainly should not have bled. The only thing to do was to smooth it over, and smoothing things over for the talent was my actual day job. That, at least, I knew how to do.

But there was still the bleeding, and I did not know what to do about that. Had I been anywhere else, I could have gotten help, or talked to someone, or called my mother, or at minimum done a damn Google search. In Sochi, all surveillance was legal, and as a preventative measure, NBC had made copies of the hard drives of all our devices — even our personal ones — before we left New York so that when we returned, they could compare the two to check for malware. If I used my phone, my computer, or the internet, NBC would know about it. The only doctor available was employed by NBC. The only people I knew in Russia were other NBC employees. I was surrounded by people whose careers, like mine, were dependent upon Matt’s success.

Maybe that was a good thing for my ignorance was the only thing allowing me to function. I was not looking for clarity but the opposite. Ambiguity allowed me to avoid acknowledging the unthinkable, which would have changed my life forever. Who would choose to be a victim if there was any other option?

I pulled the blood‑streaked sheets off the bed and piled them in the corner so that the maid would not see the blood. I wadded my bloody underwear into a ball and threw it away.

Good quarterbacks have short memories, I told myself. Good soldiers fight another day.

Good girls don’t make a fuss.

I got up and went on with my day as though absolutely nothing had happened. I was at a group meal later when my phone buzzed with a message from Matt’s NBC email to my NBC email that said something like, You don’t call, you don’t write — my feelings are hurt!

How are you?

I remember looking at everyone else at the table and realizing that they were now in a totally different world. A couple of days earlier, we’d all been listening to the new Beyoncé album during a long car ride to a shoot and my life was an open book. We’d been working closely together for years. I’d started at NBC in its famed Page Program in 2008 and first met Matt, Meredith, Ann, and Al — known to millions of morning-television viewers as “America’s First Family” — when I was assigned to the green room of Today later that year. For the next decade, 30 Rock would feel like home and my NBC colleagues like my family. If a problem was weighing on me, I could just talk about it. An argument with my mother? An email I’d missed or a dumb mistake I’d made? It wasn’t so bad; everyone had been there. This was different. Everyone had not been drunk and alone with Matt Lauer insisting on having anal sex. None of them had been there with me in that spinning room, or in my drunk, unsteady body, or my blurred, frantic mind. No one could tell me I wasn’t losing my mind or that it wasn’t my fault or that it would be okay.

I’d obviously done something wrong — You don’t call, you don’t write was talentspeak for You should have called, you should have written, you’ve screwed up. If that wasn’t clear, My feelings are hurt! drove home the point. I had no idea how to respond, but I knew that to ask anyone for help would only make it worse. Shameful secrets are like that. To trust anyone is to give them power over you. I was totally alone, drowning in plain sight.

I quickly wrote back, All good, or something similarly friendly, to show there was nothing to worry about. Ignoring the talent was not an option, and if he needed reassurance, I would reassure him. It’s never enough just to refrain from making a powerful person feel bad about something they’ve done. You have to assure them that they have no reason to feel bad at all, lest they associate that nagging, uncomfortable feeling — personal accountability — with you. We tend to avoid people who make us feel bad, and once the talent starts avoiding you for whatever reason, your days are numbered.

Yet the email was also oddly comforting. It reaffirmed exactly what I wanted and needed to believe, which was that it had all been a misunderstanding, that everything was all right, that Matt Lauer — anchor of Today — couldn’t have seen the blood or meant to cause pain. (Matt maintains the encounter in Sochi was “mutual and completely consensual.” As of publication, he has not been charged with or convicted of any crime and denies all abusive or coercive sexual conduct and nonconsensual sex with any woman at any time.) We exchanged a few more friendly emails and saw each other on set and at a group dinner as usual, but then he barely spoke to me for the rest of the trip.

In a world where Matt had no power over me and what he thought of me didn’t matter, that might have been the end of it. But this was NBC in the era of peak Matt Lauer. Initially the way forward had been clear: I would bury what happened. But after that email and the days of silence that followed, there was no way forward but panic and confusion. My only hope was to manage the situation, smooth things over, fix it.

The night before my flight home, I drank a third of a bottle of vodka, pacing and sweating as I packed. After enough alcohol, I’d worked up enough courage to clear the air and make sure Matt knew he had nothing to worry about. Then life could go on.

I emailed and asked Matt if he had time for a quick chat. No response. An hour or so later, I emailed again, saying that we were leaving Sochi tomorrow and I’d be around for the rest of the night, if he just had time for a quick chat. No response. Even the emails were risky to send, because I knew NBC could read them and security would be imaging our devices, but with each passing moment — and more vodka — I became more and more convinced that I had nothing to lose. Another hour or so later, I emailed a final time, literally begging him to call me. I remember writing something like I am just a normal person, I don’t know what you want me to do. No response. By this point, I felt like my lungs were collapsing, and the world around me with them. I was crying uncontrollably, working my way through the vodka, and then at 10:30 or 11 — who even knows what time it was — I used my NBC burner phone to call Matt’s NBC burner phone.

He answered right away. He’d obviously been sound asleep. In tears, I said I really needed to talk before I left because I didn’t know what to do.

He seemed to have no idea what I was talking about.

Then he said — as though he were trying not to wake all the way up — Come see me when we’re back in New York. Then he hung up.

I saw it as a reprieve. The moments between now and then were just borrowed time. I would go back to New York and try to survive until I could talk to him and make everything okay.

Early the next week, I found a work‑related excuse to go to Today as Matt had asked. He grinned and waved me into his dressing room, shutting the door behind us. All smiles, he was so sorry he hadn’t seen my emails, he explained — the pathetic, desperate pleadings of a terrified young woman afraid to go home, that had now been sitting in his NBC inbox for days unanswered — but if I wanted, I could come to his apartment that night. The look on his face was pleased, flattered, almost boyish. To him, apparently, those emails had been a proposition. Another opportunity. I was just relieved he wasn’t mad.

And then I was flattered. It had been a misunderstanding, that I wasn’t pathetic and weird but desirable. It meant that he was offering me a do‑over to not embarrass myself. This time I would not be drunk. This time I would never lose control. And anyway, it wasn’t like I could say “no” to Matt Lauer, sitting in his dressing room at Studio 1A in Rockefeller Plaza. It was another trap, and I walked right into it. I left feeling not trapped but triumphant.

When I arrived, he ushered me quickly through a palatial apartment into a kitchen, where he offered me a drink. It was vodka, handed to me with a grin.

I was there to block out a memory, to erase it, to replace it with one less humiliating. Matt’s objective, it seemed, was the opposite. His point, apparently, was to re‑create that memory. To reinforce it. To repeat it.

The shame flooded over me as I drank, realizing uncomfortably late that Matt was not drinking anything at all but watching me intently, the way a parent administers medicine to a child.

He says he wants to show me something. He leads me into what I would have called a walk‑in closet, though a more accurate description would have been a dressing room. I am surrounded by suits. I am at a loss. Why does he want to show me this? It is humiliating enough that I have spent years of my life carrying wardrobe bags and looking at racks of other people’s clothes that are worth more than my annual salary. He cannot possibly think that I will feel anything but poor and small surrounded by expensive suits, as if his $8 million apartment hadn’t already done the job. He unzips the back of my dress. Within moments I am sitting on the edge of a bed. He ducks out of the room and then returns, carrying an armful of towels.

Just in case, he says generously, because of what happened last time. The implications of this radiate through me. “What happened last time” could only have been the blood. He saw it in Sochi. He has known about it all along. It was not a mistake. It was not a misunderstanding. And then afterward — after he’d seen the blood — he’d asked me if I liked it, and I’d been so broken and humiliated and desperate to please him that I’d said “yes.” But that was then. Why would he have towels now?

Because he’s going to do it again.

Because that has been the plan all along.

I should have thought, He’s a monster.

Instead I thought, You brought this on yourself.

Yet I still find the courage to try to avoid the inevitable. I ask meekly, Why this?

I like it because it’s transgressive, he says, plainly acknowledging what was suddenly obvious to me — that what he likes is not intimacy but the degradation and humiliation of someone less powerful.

And then comes the trump card: You said you liked it in Sochi.

From that moment on, it is as though it is happening to someone else. He spreads the towels on the end of his bed and positions me on top. There is a rough woolen blanket that rubs my elbows as the headboard comes toward me painfully and then recedes, and I fixate on the scratching of the wool against my skin rather than what is happening. I tell myself to breathe. Then I am standing outside his door. I don’t remember getting dressed or walking out through the endless rooms of that enormous apartment or saying good-bye. I remember standing in some sort of vestibule between the elevator and his door as he shuts it in my face, and I hear his footsteps striding briskly away.

“When you say the word ‘rape,’ there’s a script that goes along with it,” says psychologist Kimberly Lonsway, Ph.D., the director of research for End Violence Against Women International. “That drives our thinking in all kinds of ways, mainly that the less a rape looks like the stereotype, the more skeptical we tend to be about it.”

If an accused rapist doesn’t align with the stereotype — a terrifying, monstrous stranger wearing a ski mask — we are more likely to doubt the allegations against them. Even though most victims are sexually assaulted by someone they already know, when their reaction doesn’t match the stereotypical stranger-danger script — they don’t scream or forcibly resist, they fail to capitalize on every potential opportunity to escape, they wait it out or act “normal” following the assault or continue their relationship with the perpetrator — we are far less likely to believe them.

“The really unique part, I think, about sexual assault is that, when you go down the list of characteristics that cause people to question whether or not this was really a sexual assault, in many cases those are the common, typical dynamics of actual sexual assault,” Lonsway says. “The very hallmarks of what sexual assault typically looks like are exactly the same characteristics that cause people to doubt the credibility of a sexual assault disclosure.” How deeply ingrained are these stereotypes, even now? Look how often people appeal to them when trying to cast doubt on victims who come forward with sexual assault allegations that don’t perfectly correspond to the stereotype.

“These are not allegations that [Weinstein] met someone in an alleyway and threw them down and committed a crime,” Arthur Aidala, Weinstein’s lead defense attorney in his 2025 New York retrial, told the jury. “These are all based on relationships, friendships.”

The jury’s verdict on the three charges against Weinstein (two counts of criminal sex acts and one count of third-degree rape) came back split: guilty on one of the charges, not guilty on another, and no verdict at all on the third, in which the judge was forced to declare a mistrial.

Earlier that year, New York published a detailed report in which multiple women alleged that best-selling author Neil Gaiman had coerced, sexually abused, and sexually assaulted them, which he categorically denied.

Gaiman’s public response in his defense? “I went back to read the messages I exchanged with the women around and following the occasions that have subsequently been reported as being abusive,” he wrote. “These messages read now as they did when I received them — of two people enjoying entirely consensual sexual relationships and wanting to see one another again. At the time I was in those relationships, they seemed positive and happy on both sides.”

Why, if an alleged victim was really sexually assaulted, would they continue a relationship with the perpetrator? Why would they go back? This is the question I have been asked too many times to count, including by Matt himself. “Brooke’s story is filled with contradictions,” he wrote in an open letter in response to Ronan Farrow’s 2019 book Catch and Kill, which describes my own and others’ allegations of sexual misconduct against Matt. “She claims our first encounter was an assault, yet she actively participated in arranging future meetings and met me at my apartment on multiple occasions to continue the affair.”

If I am walking home at night and a man in a ski mask jumps out and sexually assaults me in an alley, obviously I am not going to chase him down the street afterward and ask if he wants to go get a cup of coffee. Since the assailant is a stranger, neither his opinion of me nor his relationship to me matters. He can’t cost me a job or harm my reputation. No one in my life will blame me for getting him in trouble. But now assume that this happens as most sexual assaults actually do, within the context of a preexisting relationship. I will be much less likely to immediately recognize it as an assault. I have to consider not only whether anyone will believe me but how the allegation will impact everyone else in my life. If that means losing a job, a church, a school, or part of my family, then that’s all the more reason to convince myself that it wasn’t a sexual assault in the first place.

“The assumption is that people will be so horrified by being sexually assaulted by somebody that they will never have any subsequent contact with them, and that’s just not how it happens,” says forensic psychiatrist Barbara Ziv, M.D. “Most women are confused by the sexual assault and it takes them some time to really understand it. Almost universally, they just want to go back to the way it was before. They hope that it was just an aberrant day, hour, whatever — and they just want to go on with their life …They just want it to go back to normal, so they will have subsequent contact with the individual. It’s very common. In fact, it’s more common. It’s the exception of a woman who really understands that what happened to her was not consensual and that she didn’t invite it, that it was rape.”

This seemingly inexplicable compulsion to go back to the person who has betrayed and hurt you — is it insanity? Delusion? Denial? Weakness? It is none of these things. It is one of the most common human impulses we have. It’s plain old loss aversion. The abuse is a known quantity that the victim has already survived, but the consequences of confronting or reporting the abuser are unknowable and therefore much more terrifying.

“It’s only in the context of sexual abuse that we think this stuff is weird,” says clinical and forensic psychologist Dr. Veronique Valliere, a member of the Pennsylvania Sexual Offenders Assessment Board. “Victim behavior is not actually counterintuitive at all. It’s actually quite logical if you understand the situation. The only people not surprised by the victim’s behavior is the offender. They know. I have videotapes of these guys saying, ‘I knew she wouldn’t tell, I knew she’d come back.’”

Victims often think their silence keeps them safe, but it only makes them more vulnerable to their abusers. The abuser, after all, is the only other person who knows the secret, which makes them — in a perverse, backward way — the only person the victim believes they can trust.

In the months that followed, there would be four more instances of alleged “inappropriate sexual behavior in the workplace,” as NBC News later characterized it (Matt has consistently asserted all encounters were consensual and constituted “an affair in which [I] fully and willingly participated”). Once Matt summoned me to his dressing room and I went; two other times I ended up there in the course of my day-to-day job. One encounter I even initiated, telling myself I wasn’t the same naïve idiot I’d been in Sochi or some girl Matt could just summon to her knees in his office, always thinking that this would be the time I took back control. But I never did. I just implicated myself in my own abuse.

Every day, I felt more and more like I was being drawn into quicksand, disappearing. Everyone around me assumed I was the same fundamentally decent person I’d always been when I knew that I was not. No amount of alcohol could make that fraudulent, invisible feeling bearable, so sometimes some version of the story would come out after I’d had enough to drink. Even drunk, though, I would never have been reckless enough to say that Matt was anything other than the niceish guy he appeared to be on Today.

Somehow, I still wasn’t sure that he wasn’t. The weird, “transgressive” sex stuff — who was to say it wasn’t just something all rich, famous, older men did? Maybe I just wasn’t sophisticated enough to understand how lucky I was. I started buying new clothes, wearing higher heels and more makeup. I got garish blond highlights, straightened my curly hair, and lost weight. Matt’s point of view was reality, and in that reality, how I looked to men was all that mattered. Soon I was going to happy hours with co-workers and then staying out until four a.m., long after they’d gone home. Every reckless, bad decision became a way of proving to myself that what happened in Sochi had not been an aberration but my choice and something I deserved.

Even more confusing was that in the moments when I didn’t hate myself so much that I wanted to die, I felt more alive than ever, as though I’d become an adrenaline junkie from knowing that I could randomly walk down the hall at work and, in an instant, cross paths with someone who could ruin my life and career on a whim. The only thing more frightening than actually seeing Matt and worrying that I hadn’t been friendly or attractive enough was not seeing him and worrying that I was already on the chopping block. Should I reach out in some flirtatious, affirming way so he’d know he had no reason to worry? Or maybe that was exactly the wrong thing to do because I’d be bothering him and then becoming a problem? I had no idea, and I worried about it all the time.

So I drank, and depending on the day, I’d think about Sochi as though it was either the best thing that had ever happened to me or the worst thing I’d ever done. Either way, though, Matt could only be blameless in it. When a lion bites a lion tamer, you don’t blame the lion. Whenever I talked about it, I emphasized that I was the bad person, the cheater, the liar. Matt Lauer was Matt Lauer and that couldn’t be helped, but I should have known better, been a better person, found a better way of handling it. Until I reported Matt, I probably told about 10 or 12 people sanitized, idealized versions of what happened, never suggesting that it had been anything other than my choice.

One of those people was my mother. I’d almost convinced myself that she would be proud of me for handling the situation — and that this powerful man that even she admired had “chosen” me. Even though I’d framed the situation as positively as I could manage, there was no pride on the other end of the line. Instead, it was a low, slow, labored breathing, as though she were struggling for air.

Then she said, in a voice I would not have recognized, God damn him.

No, I told her, it was fine. I was handling it.

You think you’re being a grown‑up but you’re being a stupid little girl, she said.

It was, in all the years of my life, the meanest thing she had ever said to me. Of course, I could have no idea then of the sheer magnitude of the pain I had just caused her. Until I had a daughter of my own, I could never have imagined the primal rage she must have felt as she gathered that a powerful man nearly her age had preyed upon the body of the daughter who meant everything to her but nothing at all to him. She exhaled forcefully and her voice shifted again, the way you would punch the clutch of an old truck to pull a boulder up a mountain. You are nothing to that man but a convenience, I remember her saying. I hung up on her.

When I told a few friends who worked in other industries — oddly enough, these were my male friends in supposedly misogynistic fields like finance, consulting, sales, and politics — their faces went pale. Assistants and interns were off‑limits, they’d say; everybody knew that. They said whatever I was doing, no matter how much I loved NBC, I had to get out of there. But if I wouldn’t listen to my mother, I was never going to listen to them. What would have been the point? There was no escaping myself, and there was no escape from the shame. “I barely recognize you anymore,” said one of my oldest friends at NBC. I’d broken down and told him “something happened” in Sochi with Matt that had become “an affair.” I waited for the requisite curiosity and excitement to wash over his face. Surely he would ask what Matt was really like, or whether I knew how many of the other rumors about him were true — but he didn’t.

“Was this consensual?” he asked.

“Yes?” I said, giving myself away.

By that point, I was carrying a bottle of bourbon with me to work in the same tote bag as the Keds I wore to commute.

When I saw Matt in public work settings — when he came on Meredith’s show or she went on Today — he was perfectly nice, and so was I. I can understand why it had been so easy for me to put what happened in Sochi and at his apartment in a box and bury it: Except for when I was alone with him, he was not monstrous at all but charming and charismatic, powerfully wielding the talent that all great interviewers have of making you feel as though you’re the only person in the world. These situations are rarely perfect binaries. It’s not an either/or between Matt as a monster or me as innocent. Some of Matt’s behavior was innocuous. Some of mine — the countless lies and daily betrayals of people I loved to stay in Matt’s good graces — was monstrous, however valid my reasons for it.

It would take years — and a national reckoning with sexual harassment and assault — before I called what happened to me assault. This was October 2017 and Me Too was beginning to hit closer to home. One of my side gigs had been transcribing interviews for the book Game Change about the 2008 presidential election. When one of its authors, Mark Halperin, was fired, someone messaged me with the news. “What a mess,” I said. Then they mentioned that there was supposedly a reporter digging into Matt Lauer.

I got up from my desk, walked to the elevator, and left the building. This could not be happening. Real reporters — respectable, non‑tabloid reporters from respectable, non‑tabloid publications — never looked into the rumors surrounding Matt. Brian Stelter, while serving as a media reporter for the New York Times, had written an entire book about the brutally competitive world of morning-news shows and had barely mentioned them. Yet it quickly became apparent it wasn’t just one reporter “looking into” Matt but at least two teams of reporters from two different publications, Variety and the Times. It would only be a matter of time. All of this was going to come out, and I needed to get a lawyer. I’d never even gotten a speeding ticket fixed. I had no idea what to do, and the clock was ticking.

But would it make any difference? I was no Ashley Judd or Gretchen Carlson. I was just one woman and nobody’s ideal victim. I’d done everything wrong, and if it had taken five women coming forward with allegations against Mark Halperin, at least six for Bill O’Reilly, at least seven for Roger Ailes, how many women would have to come forward about Matt Lauer before any would be believed?

For the past nine years, NBC had been the closest thing I had to a family in New York. Since I’d moved to the city, I’d lived in six tiny apartments and walked to Rockefeller Plaza every morning from every single one of them. It felt like home. To talk to a lawyer about NBC, to even think of myself as separate from NBC, felt like a betrayal.

There was, however, another way to look at it. No matter what I did, something about Matt would inevitably come out. I didn’t know any women who had actually reported their experiences with him. In that sense, reporting Matt to NBC was not a betrayal but an act of loyalty, a way of protecting the company that felt like my family. Would it make any difference? Almost certainly not. Matt was the Today show, and I was a relatively junior and undistinguished producer. The math here was not hard. Matt was going to win.

In the end, I decided the math didn’t matter. I would never have asked anyone else to risk their career to come forward against Matt Lauer. It was a suicide mission — but when I looked back at my life since Sochi, it seemed plain enough that it’d been a suicide mission all along. NBC could investigate my claims or not, but at least I would have some small hope of being able to live with myself again. And it would be a confidential complaint. I could finally put it behind me and move on.

But that’s not the way it worked out.

Nevils in 2026.

Photo: Farrah Skeiky for New York Magazine

The day after I made my complaint, Matt was questioned by NBC and fired by NBC News chairman Andrew Lack later that night. After his firing was announced the next morning — Wednesday, November 29, 2017 — the Times and Variety published a slew of other allegations against Matt. The next day, an investigative reporter was texting my personal cell phone. Eventually a tabloid began calling my co-workers at 30 Rock, apparently asking whether they were aware that I was Matt’s “mistress who’d gotten him fired.” After that, I made it a few more months before taking a leave of absence that would ultimately prove permanent. I’d started at NBC giving studio tours, and it had taken nearly a decade to work my way up to salaried prime-time news producer. Now that life was gone, and I barely recognized the train wreck I’d become. I was compulsive, paranoid, and drinking all the time. I felt I’d ruined everything, hurt and embarrassed everyone I loved. Soon I would find myself in a psych ward, believing myself so worthless and damaged that the world would be better off without me.

Me Too was a long-overdue reckoning that asked a lot of unsettling questions it ultimately left unanswered, leaving a growing divide in its wake between those who “got it” because we’d lived it and those who didn’t because they hadn’t. I’d lived it — at the very center of it — but still didn’t get it. The questions I desperately needed answered were the ones everyone either seemed too afraid to ask or was pretending to have understood all along because no one wanted to be cast as part of the problem. Yet, again and again, I was told that nearly everything about my experience — from the choice to stay in contact with Matt, to the completely different person I’d become in the aftermath — was “textbook.” In the meantime, I was supposed to use a hashtag and call myself a survivor. I didn’t feel at all like a survivor. I felt like an idiot, set up to fail from the beginning.

We know that textbook sexual-harassment cases are rare, and we have known for years that violent, back-alley sexual assaults by strangers are less common than the messier, more confusing assaults by perpetrators the victim knows and trusts. Research has surfaced and resurfaced showing that many victims go back, many maintain relationships with their abusers, many behave in self-destructive ways that seem to defy common sense. Yet, these “imperfect” victim reactions aren’t any more part of our cultural understanding of abuse now than they were before Me Too and are instead used to discredit victims again and again. “Counterintuitive” victim behaviors do not always indicate that abuse has occurred, of course. But too often they are wrongly interpreted as red flags that it could never have occurred.

Sure, work culture has changed. Management may be less tolerant of off-color jokes and sexual advances on subordinates, but so many of our deepest assumptions about what a “real” victim should look like, and how they should behave, remain firmly entrenched. As a result, the process of coming forward is still, broadly speaking, nightmarishly complicated and often self-defeating. The number of sexual assaults that are ever reported, investigated, and prosecuted is still comparatively small. Innocent men remain terrified of false allegations, while victims still face one terrible choice after another. We are left, then, with a system that works for no one but abusers.

I know this, not because of Me Too, but because I have spent the long years since using my otherwise abandoned skills as a journalist to report and write the book about sexual harassment and assault that I wish had existed for me. In the process, I have painstakingly rebuilt my life. I got married. I had two beautiful children. Every moment with my family is a precious piece of the life that I once believed I no longer deserved to live. Yet I know that somewhere, others are trapped in the same impossible situation I once was, left with the same set of bad choices I once faced, believing they don’t deserve the futures that still lie ahead of them. To them, I would never say that the past can be fixed or changed, that justice is guaranteed, that life is fair, or that everything will be okay. I know all too well that it can’t, it isn’t, and all too likely, it won’t. I can say that I know what it is to feel truly alone and ashamed, living a life that seems irredeemable, believing yourself to be worthless and unlovable.

Not one of these things — for any one of us — is ever true.

Excerpted from Unspeakable Things, by Brooke Nevils, published on February 3, 2026, by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2026 by Brooke Nevils.