Unable to Stop AI, SAG-AFTRA Mulls a Studio Tax on Digital Performers

Call it the Tilly tax.

In the future, studios that use synthetic actors in place of humans might have to pay a royalty into a union fund.

That’s one of the ideas kicking around as SAG-AFTRA prepares to sit down with the studios on Feb. 9.

Artificial intelligence was central to the 2023 actors strike, and it’s only gotten more urgent since. Social media is awash in slop, while user-made videos of Leia and Elsa are soon to debut on Disney+. And then there’s Tilly Norwood — the digital creation that crystallized AI fears last fall. Though SAG-AFTRA won some AI protections in the strike, it can’t stop Tilly and her ilk from taking actors’ jobs.

But it might be able to extract payment for it.

“Is that a perfect solution? No,” says Brendan Bradley, a member of the union’s AI task force. “But it’s under the category of the best bad idea we’ve got in 2026.”

The threat of another strike is always on the table, but for now the alert level is low. SAG-AFTRA has agreed to bargain unusually early, months ahead of the June 30 contract expiration, and there has even been optimistic chatter about wrapping up a deal in March.

The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers has a new lead negotiator, Greg Hessinger, a former SAG leader. Early indications suggest he might be more flexible than his predecessor, Carol Lombardini, whose favorite word, according to frustrated union officials, was “No.”

An AMPTP spokesman says the studios look forward to reaching a “fair deal” that supports actors and the industry’s long-term stability.

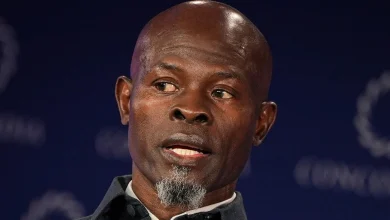

SAG-AFTRA chief negotiator Duncan Crabtree-Ireland and president Sean Astin are preparing to sit down with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers next month.

Rocco Cesselin/SAG-AFTRA

AI is a headline issue, but by no means the only one. The transition to streaming was also key to the strike, and the resulting deal left unfinished business.

“The No. 1 thing is still residuals,” says Kate Bond, a strike captain in 2023 and a member of the union’s L.A. board. “Is there a way to make it so when a show goes up on a streaming platform, we get the equivalent amount of money as a network residual?”

At one point during the strike, SAG-AFTRA demanded 1% of streamers’ total revenues — or about $500 million a year. The union settled for a streaming “success bonus” projected at $40 million annually, though it has come in well below that.

Union negotiators are expected to push to improve the terms. But some actors remain profoundly dissatisfied with the compromise.

In the days of broadcast and cable, actors would be paid for every rerun. An actor on a hit show could

sustain a middle-class lifestyle for years on the back of residuals. Reruns don’t exist on streaming, and

residuals are a comparative pittance.

“I think we’ve lost our way when we’re negotiating bonuses instead of residuals,” says Jeffrey Reeves, an actor who has been critical of union leadership. “We’ve given up the pay-per-play or pay-per-audience model.”

Streaming shows also have lengthier hiatuses between seasons — sometimes as long as several years. SAG-AFTRA has tried to limit exclusivity provisions, which prevent series regulars from seeking work on other shows during downtime, and that is expected to be an issue in the coming talks.

Some also remain unhappy with self-taped auditions — a COVID-era innovation that requires many actors to invest in home studios to try out for roles.

But the most existential fear remains AI. After the 2023 strike, the union waged a yearlong strike against video game companies over AI. And in deals with record labels and commercial producers, it has won royalties for wholly synthetic performances. For union commercials, if an actor is replaced by an AI performer, the equivalent pay has to go into the SAG-AFTRA pension and health funds.

Actors remain aghast at the idea of being replaced by a digital amalgam of other actors’ performances — or having their own performances used to replace others.

“No actor wants that,” says Erik Passoja, a former co-chair of the union’s L.A. New Technology Committee. He sees a “Tilly tax” as a last resort.

“I say no, no and triple no,” he says. “But if it has to be, it should go into pension and health.”