Possible Sudden Stratospheric Warming in early February could roll the dice towards colder weather

The weather models have for a while been signalling the potential for a major Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) event to occur in early February 2026.

This disruption to the stratospheric polar vortex could be exceptionally strong. If the SSW does occur, it will feature a rapid warming in the Arctic stratosphere, which will then likely cause a breakdown of the polar vortex, significantly increasing the risk of cold snaps, blocking patterns, and high-impact weather across the Northern Hemisphere (North America and Europe) 2–6 weeks later.

Current model data from major weather models like the ECMWF and GFS indicate a “textbook major disruption,” with stratospheric temperatures over the Arctic projected to spike by 40–50°C within days.

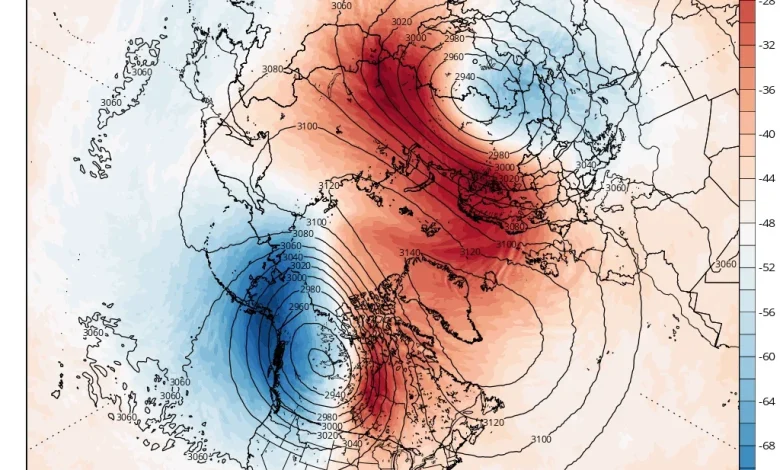

The SSW event the ECMWF and GFS have been persistently predicting is expected to significantly weaken and potentially split the polar vortex into two ‘daughter’ vortices —one drifting toward Eurasia and the other toward North America.

The 00z GFS operational run and ensemble mean show a reversal starting on the 9th February, with a split developing soon after, with a rapid downwelling of the reversal into the troposphere.

The polar vortex is a spinning vortex of cold air balanced on the Arctic, imagine it like a spinning top. When waves of energy from the lower atmosphere pulse upward – amplified by mountain ranges, storm tracks and unusual ocean heat – they smack into that top. If the waves are strong enough, the vortex slows, wobbles and can split into two or more pieces.

The high-altitude westerly winds (the polar night jet), which wrap around the polar vortex and keep the cold air bottled up over the arctic, are forecast to slow and potentially reverse direction to easterly in early February, which is a signature of a major SSW event.

While an SSW occurs 10–50 km high in the atmosphere, it can significantly alter weather patterns at ground level after a delay of a few weeks or more while the reversal to easterly winds propagate down from the upper stratosphere down to the troposphere (where our weather happens).

Surface effects from the SSW typically emerge 10 to 20 days after the peak stratospheric warming.

Potential impacts on surface weather following this potential SSW in early February may include a heightened risk of severe cold snaps or spells and associated wintry hazards – caused by high latitude “blocking” patterns (stalled weather systems) across North America, Europe, and parts of Asia throughout February and potentially into early March.

Sub-seasonal ECMWF weekly charts (updated Monday below) show presence of high pressure to the north and low pressure to the south in Febraury, perhaps as a result of a SSW, which would encourage colder than average temperatures

MSLP (reds=higher pressure, blues=lower pressure)

2m temperatures

However, a SSW does not guarantee much colder and wintry weather will occur, such as the “Beast from the East”, e.g. late February 2018; rather, it “reloads the dice” by making extreme winter patterns more likely.

Statistically, around 2 out of 3 major SSWs that lead to a split polar vortex go on to bring severe cold spells to the UK and Ireland. Some may bring no change to the weather patterns that have prevailed until the SSW occurred or may even bring milder weather. Much of this depends on what weather patterns are in place at the time as the reversal propagating down reaches the troposphere. Also how the polar vortex splits and where the two daughter vortices go. Not all places that one of the vortices may drift can be favourable for cold patterns developing over the UK.

If a major SSW does occur, we won’t know for a while after it occurs how it impacts weather patterns and whether this will then favour cold spells to develop, such as the Beast from the East.