Before becoming an alleged narco kingpin, Ryan Wedding was just a snowboard-loving kid from Coquitlam, B.C.

Before Ryan Wedding gained infamy as the Olympic snowboarder turned alleged murderous cocaine kingpin, he was just another kid from Coquitlam, B.C., getting his name misspelled in his school year book.

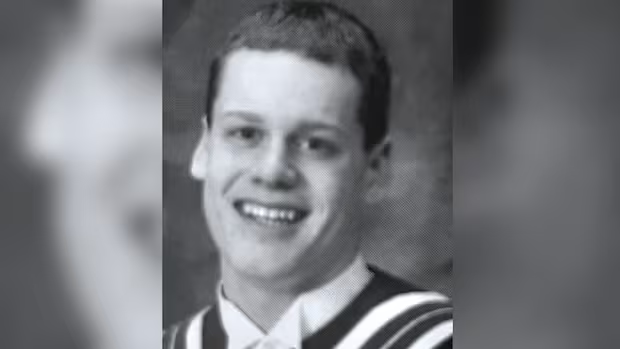

The typo says “Bryan” Wedding, but there’s no mistaking the graduation photo of the boy with the big smile in the 1999 Centennial High School year book is in fact Ryan Wedding, accompanied by a goofy reference to a 1980s sitcom.

Fast forward 27 years, and it’s Wedding who’s the boss now, at least according to U.S. FBI indictments that accuse the 44-year-old of masterminding a violent and vast narco-empire responsible for moving tonnes of cocaine and methamphetamine from Central and South America into the United States, Canada and beyond.

How a kid with Olympian talents from a sleepy Vancouver suburb ended up being compared to drug lords Pablo Escobar and Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, is hard to wrap your head around.

He’s also alleged to have orchestrated four murders — three of those in Canada. Late last year, the reward offered for information leading to his arrest was increased to $15 million US.

Two-time Canadian Olympic snowboarder Alexa Loo recalls meeting Wedding for the first time in the mid 1990s. Loo was training with the Blackcomb Snowboard Club and Wedding, age 13, had just become the youngest members of the squad.

A typo meant Ryan Wedding was listed as “Bryan” Wedding in the 1999 Centennial High School yearbook. (Centennial 1999 yearbook)

“His parents had a place in the Aspens (a complex on Blackcomb Mountain in Whistler) so they would come up every weekend with their kids,” she said. “He was this goofy kid, but very outgoing, very personable. But also sassy.”

Loo said Wedding was above average size for his age, “like a big Labrador puppy,” something he used to his advantage.

“I remember we were in Colorado and he took the biggest room and the biggest bed. Normally we’d do rock, paper, scissors for it, but Ryan was like, ‘I’m the biggest, what are you gonna do about it?’”

Wedding competed in his first major international snowboard race at age 16, finishing 11th in giant slalom, according to online records.

He won silver and bronze medals at the Junior World Championships, and became a regular on the World Cup circuit, considered the big leagues of snowboard racing. In 2001, he was crowned Canadian champion at Big White in Kelowna.

Ryan Wedding on the top of the podium at Big White, near Kelowna, B.C. (submitted by Alexa Loo)

Ross Rebagliati, first ever Olympic men’s snowboard champion, remembers being impressed by Wedding when he broke onto the national team.

“He was super confident and didn’t hold back on course,” said Rebagliati. “He just really went for it all the time and had a good attitude about training.

“He seemed like a natural athlete and … didn’t really raise any red flags or anything — other than the fact that he was probably gonna be hard to beat.”

Ryan Wedding in an undated photo taken at a training camp in Austria. (submitted by Alexa Loo)

When the 2002 Winter Olympics rolled around, hopes were high for the Canadian men’s snowboard team.

Rebagliati had set the standard with his gold medal four years earlier, and Wedding was one of three Canadians who qualified to compete in the new Olympic event of parallel giant slalom (PGS).

In PGS riders go head-to-head in pairs down a course with the winner advancing to the next round until a gold medalist is decided. In order to qualify for the knockout rounds, however, racers first do an individual time trial with only the fastest 16 advancing.

Wedding didn’t make the cut in Salt Lake City, finishing 24th in the time trial, 1.12 seconds slower that the final qualifier. It was a quick and disappointing end to his Olympic campaign.

The next month his snowboard career ended unceremoniously with a DNF (Did Not Finish) at the U.S. National Championships at Northstar Mountain in California, his final race of record.

It’s sad irony that years later, Wedding’s snowboard achievements would inspire the FBI to name their campaign to capture him and his network “Operation Giant Slalom.”

Composite illustration featuring Ryan Wedding in handout stills. (U.S. Embassy in Mexico, FBI Los Angeles/X)

After the 2002 Olympics he seemed on the straight and narrow, enrolling at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby. Loo recalls that he also started working as a bouncer at a New Westminster bar called BarFly.

The last time she saw Wedding was during a chance meeting at the Vancouver passport office in 2006, hardly recognizing the big man giving her a hug.

“This guy comes up to me and he’s got a wife-beater on, tats and necklaces, his hat on backwards. And I’m like, dude … go stand somewhere else. Like, mother of god! I’m trying to get a passport and you look like a gangster! He just laughed.”

Canadian Ryan Wedding, 44, was arrested in Mexico City and is now in custody in the U.S. (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

The International Olympic Committee tracks the achievements of Olympians on its website, normally listing significant results and a short athlete biography.

Wedding’s page, however, chronicles the early days of him breaking bad. It cites the 2006 bust of an illegal cannabis grow-op in Maple Ridge, B.C., that he was connected to, followed by his arrest in California two years later for trying to buy cocaine from a U.S. government agent. For that he served four years in U.S. prison.

Perhaps least surprising about Wedding’s story is that it’s now the subject of a documentary series: Snow King: From Olympian to Narco. CBC is a co-producer of the production, described as a “stranger-than-fiction Canadian story.”

While he’s not the first elite athlete to turn to the darkside, there is something about snowboarding’s counter culture vibe and the mega success — if you can call it that — Wedding found in the drug world. That is, before his downfall.

The FBI released photos of items seized in Mexico belonging to Wedding, including two Canadian Snowboard Federation gold medals. (Canadian Olympic Committee/Los Angeles FBI)

Rebagliati, who gained fame and infamy of his own when he was stripped of and then re-awarded his Olympic gold medal after testing positive for marijuana, says it’s wrong to view snowboarding as a gateway to poor choices.

“There’s absolutely no correlation, I would argue, between the sport itself and what anybody might end up choosing to do in their own personal life. I think you can draw comparisons to pretty much any sport with shady activities on and off the field,” he said.

CEO of his own Ross’ Gold cannabis brand for over 25 years, Rebagliati used his profile to build a career of a different sort.

“I guess it’s just like a romantic, mysterious stigma that snowboarding has,” he said. “It just keeps snowboarding a little bit on the edgy side, which is where I think the sport thrives.”

Loo, a longtime city councillor in Richmond, B.C., and professional accountant, feels only sadness for her former teammate.

“Had we maybe done a better job of harnessing his energy, his ability to think and create and strategize, maybe Ryan could have been doing something really special for the country instead of hurting people,” she said.

A few weeks ago the FBI released photos of items seized in Mexico owned by Wedding, including the two Canadian Snowboard Federation gold medals he won to qualify for the 2002 Olympic team.

Wedding was captured last week in Mexico after evading authorities for almost a decade. He’s pleaded not guilty to a slew of charges including murder, drug trafficking, witness tampering and money laundering. His next court date in the U.S. is Feb. 11.