How Joe Namath Transformed the Super Bowl

Rose Namath packed a small green suitcase with tan stitching around its edges. She gave her son a kiss and five dollars.

On that summer day in 1961, the woman who had raised five kids said goodbye to her youngest. She handed the suitcase to her son, walked up to Alabama assistant football coach Howard Schnellenberger and gave a three-word instruction.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our website.

Manage Cookies

Take him, Coach.

With that, Rose Namath thought she was sending her son to Tuscaloosa. Instead, she was releasing him to a nation that would come to see him as an icon in sports and society.

Joe Namath is 82 years old now. He’s had both knees and hips replaced, but only one shoulder. The left one has held out. He exercises four times a week, 20 minutes a day. Just enough to get the heart rate above normal. Nothing where he jams the joints. He mentions this more than a few times. Some days it’s in the water, others it’s a NordicTrack.

But no jamming.

Namath is a grandfather of six and a dad to two daughters. The older one, Jessica, lives in a South Florida home that shares a property line with his. The younger, Olivia, is temporarily staying with Namath along with her children.

On this October afternoon, Namath has come to the Jupiter Beach Resort & Spa to talk about his life. About what more than eight decades spinning around the sun has taught him. And about a game played in 1969 that changed the face of pro football. A game that helped turn the sport’s pinnacle, the Super Bowl, into a uniquely American holiday.

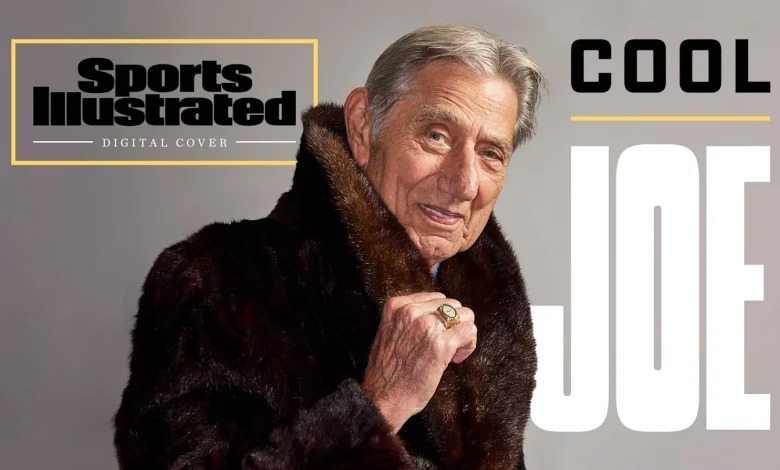

Joe Namath is still cool. | Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

January 12, 1969. Overcast and 66 degrees. Super Bowl III was in Miami, a city Namath knew well. A city where he won the Orange Bowl with the Tide on New Year’s Day 1963 and, despite losing to Texas in the same game two years later, where Alabama clinched a national championship.

Namath’s New York Jets weren’t supposed to matter. They were to be a noncompetitive footnote against the Colts, an 18-point favorite after going 13–1 behind quarterback Earl Morrall. In the NFL title game a week earlier, Baltimore had humiliated the Browns, 34–0, avenging its only loss of the season.

That same weekend, the Jets were fighting for their own crown. The night prior to the American Football League title game, Namath stayed at the Summit Hotel in midtown Manhattan to lend his brownstone to family in town for the contest. They caught the ultimate Broadway show, as Namath led the Jets to a 27–23 victory over the Raiders, the team that had beaten them in the infamous Heidi Bowl only six weeks earlier.

Yet the win didn’t mean much nationally. After all, the same Raiders had been trounced in Super Bowl II by Vince Lombardi’s Packers, 33–14. The year prior, Green Bay had humiliated the Chiefs in the inaugural Super Bowl, 35–10.

Still, the odds didn’t bother Namath. And why should they? He’d won all his life, in high school and at Bama. With the Jets, he took a moribund team to the Super Bowl in his fourth year. Now Namath was one win away from another championship. A win Namath famously guaranteed at the Miami Touchdown Club three days before the game. Coach Weeb Ewbank was furious.

“I didn’t regret saying that a bit. It was something that I believed in,” Namath says. “The next morning, after I had said we were going to win the game, [Ewbank] called me out in the center of the field before practice. He folded those arms. You could tell with him, when he had his arms folded like that, he wasn’t a happy guy.

“I ran out there, I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ He said, ‘You know what you’ve done? You know what you’ve done?’ … He was really upset, but I swear to you, I said, ‘Well, Coach, we’re going to win, aren’t we? You’re the one that’s giving us confidence. You’re the one that made me feel that way. Shucks. I’m just telling them what you told us. He said, ‘Get out of here.’ He chased me off, but the guys felt good.”

Namath’s optimism stemmed from the fact that he believed that Morrall, while a quality quarterback, wasn’t the caliber of AFL signal-callers such as the Raiders’ Daryle Lamonica and the Chiefs’ Len Dawson. And he had a sense that Baltimore wasn’t going to alter its game plan for the Jets. “After looking at the film, they weren’t going to change for us, and that was a big thing,” Namath says. “The [Colts’] defense was a wonderful defense, but when it came to the passing game especially, you could read what they were going to do.”

As kickoff neared at 3:05 p.m., No. 12 stood on the New York sideline, wearing eye black and white shoes, waiting for Colts kicker Lou Michaels, a man he had nearly fought at a bar earlier in the week, to send the ball skyward.

In three hours, football would be changed forever.

The Jets were 18-point underdogs in Super Bowl III, but Joe Namath guaranteed a victory. | Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

The suitcase sits in Namath’s exercise room, up on a white shelf in front of a green wall. Jets’ colors. When it comes into sight, Namath thinks about what it represents. After all, nobody keeps luggage for 64 years unless it carries a lot more than a few shirts and a pair of pants.

On his first trip home from Tuscaloosa for Christmas in 1961, Namath stuck three decals on the suitcase. On one side, an Alabama Club emblem in the top left corner, and in the bottom right, seven baby elephants with a letter on each spelling out ALABAMA. On the reverse, a sticker reading ROLL CRIMSON TIDE ROLL. Somehow, they still remain affixed. “This is an old friend,” Namath says, holding the two-latch suitcase on his knee. “I look at it every time I’m doing my exercises. I have great memories. Some tough times at Alabama, but we did it there. We won a championship and I made a lot of lifelong friends to this day.”

Namath’s life is a giant unpacking of the moments and places that created one of the most famous men of his era. A man who had his own TV show. A man so threatening to others that he was the only athlete on President Richard Nixon’s famed enemies list, likely because he represented the burgeoning counterculture during the height of the Vietnam War.

Namath is his own man, born in a small western Pennsylvania town called Beaver Falls. A product of having three older brothers and an adopted older sister, Rita, who doubled as a mother when Rose was pulling midday shifts at the local five-and-dime.

It was there in the heart of the Rust Belt that he learned to hustle, sometimes going to the local metal scrapyard with his childhood best friend, Linwood Alford, and stealing materials before returning and trying to sell them back. If he wasn’t earning a few dollars there, he could be found at the pool hall, trying to win some scratch at billiards before calling it a night. Sometimes he took home a paycheck on the level, working as a caddie. One dollar an hour.

While Namath has never been short of confidence, he realizes he’s always had plenty of help. “We didn’t take anything for granted,” Namath says. “Everyone worked—my mother worked, dad, brothers. I worked, and it was a great town to be brought up in. And we had good schools and I got lucky my junior year and had a great coach come in.”

The coach was Larry Bruno, a part-time magician and full-time mentor, the man who taught Namath how to play quarterback. Then there was Bear Bryant and Ewbank, two men who couldn’t have had more differing styles.

“Coach Ewbank came from the coaching cradle, so to speak, of Ohio,” Namath said. “I had watched him coach the Baltimore Colts on television. He was a wonderful man, never said a curse word. Dadgummit, you know? He respected everybody, and he got the respect from us.”

When Namath arrived in New York, it was the first time he had ever lived in a big city. Soon, he would have it all. The girls. A nightclub. An apartment decorated by the same designer Frank Sinatra employed. He’d become friends with Ol’ Blue Eyes, who referred to Namath as “Broken Knee.”

Few have ever owned a city or a time like Namath.

During the AFL championship game, Namath’s top target, All-Pro receiver Don Maynard, had pulled a hamstring, limiting him to decoy duty in the Super Bowl. Baltimore, which wasn’t aware of the injury, spent the afternoon doubling the future Hall of Famer, rotating coverage to him all game. Maynard, the humble Texan who never bought a winter coat to save money, who fancied himself an amateur plumber and mechanic to avoid spending a dime, who once chastised Namath about using too much toothpaste because the tube would run out too quickly, was as valuable hobbling around as he was catching passes.

On that January day, two men largely forgotten to history were central figures in the New York attack: Dave Herman and George Sauer.

Herman, a right guard, had the herculean task of switching spots with right tackle Sam Walton to take on Bubba Smith, the Colts’ All-Pro pass rusher. Smith, 6’ 7″ and 265 pounds, was Baltimore’s best. Herman had never played tackle before the AFL title game. “Bubba Smith was from Michigan State, and Dave Herman was from Michigan State too, and Dave did a job,” Namath says. “Boy, Bubba, he was a wonderful player, but Dave stayed in his chest all day long.”

As for Sauer, the lanky 195-pound flanker had the game of a lifetime. He caught eight passes for 133 yards. Maynard was targeted just five times without a catch, the only game that season in which he was blanked.

In the second quarter of a scoreless game, New York faced second-and-goal from the 4-yard line. Namath called 19 Reach, a run to the left designed for fullback Matt Snell. The quarterback known for his late nights had studied hard. He knew Baltimore would come out in a tight 5–1 alignment, trying to plug up any inside run.

New York went on Namath’s first sound, and Snell swept off the left side for the game’s first touchdown.

By halftime, the Colts had missed two field goals and Morrall, the NFL MVP, had thrown three interceptions as his team trailed 7–0.

Joe Namath became an icon, and not only for his exploits on the field. | Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated

Namath is sitting in a white chair with a pillow behind his back. He’s wearing olive slacks with impeccable pleats and a button-down dress shirt. On the wall is a flat-screen television displaying an image of him with the Jets, right arm cocked, looking for a receiver. Namath likes the picture. He takes an extended look, remembering past glory. Glory that seems a lifetime ago. Glory that feels like yesterday.

On a hotel cart, Namath and Jessica have brought priceless items of yesteryear. There’s Namath’s favorite photo, of Ewbank with his arms raised in celebration; two mink coats; his Pro Football Hall of Fame jacket; a portrait by LeRoy Neiman; a baseball signed by Ted Williams inscribed big-league best; and, of course, the suitcase. There were also Namath’s rings, including possibly the most famous Super Bowl ring ever minted. Among the jewelry is an obvious omission. His ring from Alabama’s 1964 national championship.

The ring, though, isn’t missing. It’s at Mount Carmel Cemetery in West Blocton, Ala., six feet underground. It was given to a student manager who never played a down for the Tide. Unlike Namath, he wasn’t reinstated after the two were suspended by Bryant after they violated the team’s no-drinking policy in 1963.

“He was a buddy, so I gave it to him,” Namath says. “He wore it to his grave. He was wearing his ring in his casket the last time I saw him. Mr. Hoot Owl Hicks was his name.”

Jack Hicks died in 2009, an eternal champion.

The ring, and where it ended up, provides an insight into Namath, a man more substance than his considerable style.

Of course, Namath’s reputation as a playboy was well-earned. He ran in many circles with many women on his golden right arm, wore those mink coats in nightclubs and on the sideline, spent time at Toots Shor’s and the 21 Club and famously did a commercial wearing Beautymist pantyhose.

But at his core, Namath is a family man who loves football. He still watches the Crimson Tide and Jets most fall weekends. He picks up the grandkids from school and hangs their drawings on the refrigerator. His walls aren’t covered with mementos of himself. That space is reserved for those he loves.

At 82 years old, far more time is behind than ahead. It would be easy to look back and crave the days gone by. But Namath is focused on the moment. He’s thinking about his restaurants in South Florida and his golf outing on Long Island for the Joe Namath Charitable Foundation. He’s thinking about his next workout. Again, no jamming the joints.

Joe Namath still has his Super Bowl III ring, unlike the one he got for winning a championship at Alabama. | Jeffery A. Salter/Sports Illustrated

On the first play of the second half, Colts fullback Tom Matte fumbled, and it was recovered by Ralph Baker. The Jets converted the turnover into a Jim Turner field goal, taking a 10–0 lead. Turner kicked two more field goals, giving New York a 16–0 advantage with 13:58 remaining.

Baltimore coach Don Shula replaced Morrall with Johnny Unitas, Namath’s idol and fellow western Pennsylvanian. Unitas was known for his many fourth-quarter comebacks, including the infamous two-minute drill to lead the Colts past the Giants in the 1958 NFL championship game. Ewbank was Unitas’s coach that day. Maynard, a rookie, was on the Giants’ sideline. They knew the greatness.

But it was too late. Though Unitas led a touchdown drive in the waning minutes, Namath, who was known for his pass-happy ways, decided to run the ball with the Colts seemingly unable to score against New York’s defense. “There was a time late in the game when Baltimore called a timeout,” Namath says. “I go over to the sideline, and Coach Ewbank asked me what I thought. He asked me about a pass play, and [defensive coordinator] Buddy Ryan was standing right beside him. I saw Buddy, and I said, ‘You know, Coach, they haven’t scored on our defense yet. I’d rather keep the clock running.’ Buddy just turned, and he went over to the defense right away. I know he was happy to hear that.”

Finally, the gun sounded. The Jets won 16–7. The 18-point underdogs danced off the field. Namath ran toward the Orange Bowl tunnel surrounded by a throng of photographers, teammates, fans and reporters, putting his right index finger in the air to signify what everyone watching already knew. “I had never in my life done one of those things, putting my hand up like that,” he says.

In the locker room, Namath stood in his stall, his white uniform covered in grass stains. He shared a moment with his brother Bob and father, John. Then, Namath left in a black town car with friend and roommate Joe Hirsch, and a woman he prefers not to name, just in case her husband reads this story.

On the ride to the Gait Ocean Mile Hotel, the three sat quietly. Namath was too worn out to think. Hirsch was driving, and both he and the woman waited for their cue to speak. “We started driving, God, I don’t know, it seemed like four or five minutes,” Namath says. “Might have only been a minute. And we were dead silent. Not one of us spoke a word. Then, all of a sudden, Joe just started his gentle laugh, and she started laughing, and I started. Yes, we really felt good.”

Unlike today, there was no lavish postgame party with A-list entertainers and hangers-on at the hotel. Instead, there was a trio of large men with tears in their eyes. “We were No. 1, the AFL. We did it,” Namath says. “There were three guys, [Chiefs’ stars] Bobby Bell, Emmitt Thomas and Buck Buchanan. They were waiting for us. They were waiting for us, and they were thanking us. They won it the next year … I’m getting goosebumps talking about that.”

Joe Namath and the Jets were all smiles after winning it all in a stadium he knew well. | Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

Before the game, Super Bowl I was seen as a curiosity. The NFL was expected to crush the upstart AFL, which had only been in existence for seven years. The first two games had been lopsided, and so was public opinion. The two leagues, which agreed in 1966 to merge for the ’70 season, were unequal.

But Super Bowl III changed everything.

While the embarrassment was total that night, NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle understood the bigger picture. There had been rumors about the league having to reimagine the postseason because of how inferior the AFL appeared to be.

New York’s win took care of those conversations. And for anybody harboring doubt, the Chiefs smashed the Vikings the following year in Super Bowl IV, 23–7.

“See, this is the thing,” Namath says. “We had lost the first two [Super Bowls]. Now, when you’re a kid playing wherever, if you lose three out of three, what are you? You’re gone. You’re history. No respect whatsoever. We won the third one. Then [the Chiefs] won that fourth one.”

Super Bowl III had a viewership of 41.6 million, with a 30-second TV advertisement costing $55,000. One year later, the Chiefs-Vikings Super Bowl saw the price of a commercial jump 42.2% in value.

For Super Bowl LIX last February, a record 127.7 million people tuned in while a 30-second spot cost an average of $8 million.

Sixty-four years ago, Rose Namath sent her son to Alabama with five dollars in one hand and a green suitcase in the other. The bill is long gone, but Joe still has the luggage. It is a through line that starts when a scared kid left with a stranger to go live in an unseen town 827 miles away, in a segregated South. Then to New York City and on to Los Angeles for one ill-fated season before retirement in 1978. A constant in different houses, different locations and different stages of a life many would envy.

After an hour and a half of reminiscing and posing for photos, Namath is ready to head home now. As he gets into his cream-colored Cadillac Escalade, he shakes hands and says goodbye. The items he brought are loaded into the vehicle—the pictures, rings, minks and Hall of Fame jacket. And the suitcase.

The suitcase is ready to go back on his white shelf in front of the green wall, put back in its reserved space.

Ready for its next adventure, just like the man who owns it.