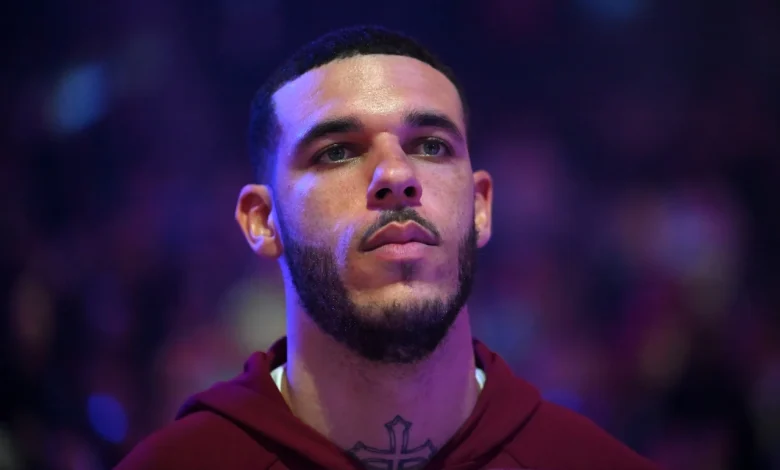

Cavs trading Lonzo Ball to Utah Jazz

CLEVELAND, Ohio — The Cavs are moving on from their offseason gamble.

Cleveland is trading Lonzo Ball and two second-round picks to the Utah Jazz, league sources confirmed to cleveland.com. Utah is expected to waive Ball after the deal is finalized, ending his brief and uneven stint with the Cavs just months after the organization acquired him in a calculated bet on health, fit and financial flexibility.

The move allows Cleveland to shed Ball’s $10 million salary and inch closer to dropping below the NBA’s restrictive second apron, a critical threshold that has loomed over nearly every front-office decision ahead of the trade deadline. The cost, however, is real. The Cavs surrendered their only remaining second-round picks in 2028 and 2032 and now do not control a single second-rounder through 2033.

Moving out of the second apron would ensure the Cavaliers’ 2033 first-round pick will not be frozen. Under the league’s current CBA, teams that finish the year above the second apron have their first-round pick seven seasons out frozen, which means it cannot be moved in trades.

In the most immediate sense, this was a financial and structural decision. In a broader sense, it was an admission that the on-court experiment never materialized the way Cleveland envisioned.

At the time, the Cavs believed they were buying low on a high-IQ connector guard who could elevate their offense without dominating the ball. Ball’s vision, hit-ahead passing and willingness to move the ball fit neatly into Cleveland’s drive-kick-swing identity on paper. If healthy, he projected as a stabilizing sixth man alongside Dean Wade when De’Andre Hunter occupied a starting role.

Instead, Ball struggled almost from the start.

By dumping Ball’s salary, the Cavaliers are projected to slash their luxury tax bill from roughly $120 million to $65 million. Just as important, the deal opens a full roster spot, clearing the path for Cleveland to convert Nae’Qwan Tomlin’s two-way contract to a standard NBA deal.

Ball arrived in Cleveland as part of an offseason trade that sent Isaac Okoro to Chicago.

How to watch the Cavs: See how to watch the Cavs games with this handy game-by-game TV schedule.

After opening the season as the Cavs’ sixth man, Ball steadily slid down the rotation. His minutes dwindled as his efficiency cratered, and by midseason he had been leapfrogged by third-year guard Craig Porter Jr., whose downhill pressure and defensive versatility provided what Ball could not.

Ball finished his Cleveland tenure with one of the worst field-goal percentages and 3-point percentages in the league. He shot just 30.1% from the field and 27.2% from three in limited action, numbers that undercut the very spacing Cleveland hoped he would provide.

More problematic was his inability to consistently generate dribble penetration in the half court, which was critical for a Cavs offense built on collapsing defenses and initiating their drive-kick-swing sequence to terrorize opponents.

Without that pressure, Cleveland’s offense bogged down. The physical limitations that have followed him for much of his career, particularly after multiple knee surgeries, made it difficult for him to turn those reads into advantages.

Ball has never lacked basketball intelligence. But availability has always been the swing factor. Ball has played just 322 games across nine seasons, missing significant time with knee issues that sapped his burst and altered his offensive profile. Cleveland knew the medical risk when it traded for him. The hope was that a defined role, reduced usage and a strong infrastructure could maximize what remained. It didn’t work.

The Cavs now face the other side of that gamble. By moving on from Ball, Cleveland has cleared salary and regained some flexibility under the second apron, a line that severely limits roster-building tools. Teams above the apron lose access to the midlevel exception, face restrictions in aggregating salaries in trades and are limited in their ability to take back additional money. For a contender with limited draft capital and a tight cap sheet, every penny counts.

Still, the trade underscores the cascading cost of the original decision. Cleveland no longer has Okoro, its best perimeter defender. It no longer has two second-round picks that could have been used in future trades or roster maintenance. And now it no longer has Ball, the upside swing that justified those risks in the first place.

In the short term, Porter’s rise and the continued emphasis on guards who can collapse the defense simplify the rotation. In the long term, the Cavs are prioritizing financial maneuverability and clarity over theoretical upside.

This wasn’t a move made in a vacuum. It was the end of a bet that didn’t pay off — and a reminder that for a team walking the tightrope of contention and cap constraints, every swing carries consequences.