Mickey Lolich, Detroit Tigers’ 1968 World Series hero, dies at 85

He was a striking figure in Tigers history — a fascinating model of industry, reliance, and, when the moment called for it, grandeur.

And now, Mickey Lolich is gone. He died Wednesday at the age of 85, the Tigers confirmed.

“The Detroit Tigers are deeply saddened to learn of the loss of Michael Stephen ‘Mickey’ Lolich, who passed away today at the age of 85,” the Tigers said in a statement Wednesday. “Everyone with the Detroit Tigers extends their heartfelt condolences to Lolich’s wife Joyce and the entire Lolich family.

“His legacy — on and off the field — will forever be cherished.”

No pitcher in 125 years of Tigers big-league life was so tied to durability, or so paired his seeming indestructibility with such excellence during his time in Detroit. No pitcher in Tigers history quite matched his knack for taking on inhuman workloads that could forge even greater gallantry at big-game moments. It was a gift defined especially by his work leading the Tigers to a World Series ambush and world championship in 1968, when he won three games, with the final two coming three days apart, including the grand finale — a seventh-game, ace-pilot shootdown of St. Louis Cardinals pitching deity, Bob Gibson.

That triumph, fueled by Lolich’s astounding energy and command, was a come-from-behind tale of such lore and heroism that it adorned Lolich throughout the rest of his life, which was spent with typical simplicity in Macomb County’s suburban northeast sector.

Lolich pitched 16 big-league seasons, with the first 13, from 1963-75, spent in Detroit. Throughout the years came performances that invited one to ask if Lolich was flesh and blood, or steel and bolts.

One season, as much as his wizardry at the ‘68 World Series, defined Lolich’s indefatigability: 1971, when he threw an astonishing 376 innings, nearly three times a typical starting pitcher’s quota, and struck out 308 batters. He pitched 327 innings in 1972, and 308 in both the 1973 and ’74 seasons.

It was as if he had his own take on what the body could do.

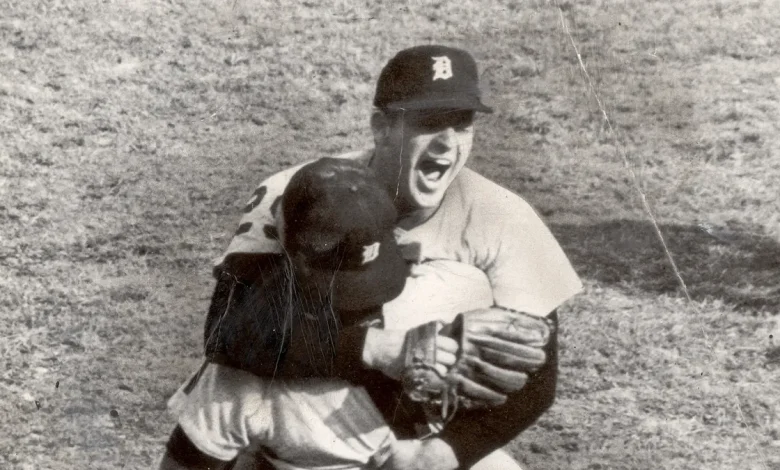

It had been an unwieldy, colorful, sometimes distressing path Lolich had traipsed ahead of that crowning moment in St. Louis on Oct. 10, 1968, when he jumped into catcher Bill Freehan’s arms. It’s an image that became ― and has remained, all these years later ― one of the most-famous photographs in franchise history.

Soon after the the final out, the champagne corks popped in the Tigers clubhouse.

Lolich, in the process of winning a new car as World Series MVP, also had upstaged his pitching mate and sometimes-irritant, Denny McLain, who during the regular season that year had won 31 games — still the only pitcher since Dizzy Dean did it in 1934 to bag 30 victories in a single MLB season.

Lolich all but shrugged. The World Series was important — the personal celebrity less so. His was a persona that helped make Lolich a Tigers star as unassuming as he was remarkable.

With a rat-ta-tat-tat giggle that was a dead giveaway for a man who loved humor, even at his own expense, Lolich was relaxed more than low-key. He was a man at once simple and disarmingly humble, yet proud of his big-league years and the legacy he had forged in Detroit.

His career, which included late stints with the New York Mets and San Diego Padres, flirted on the fringes of Baseball Hall of Fame consideration and might someday win for him a posthumous plaque in Cooperstown.

“There is no reason why in the world he is not in the Hall of Fame,” McLain said Wednesday. “None.”

Only four left-handed starting pitchers in major-league history — Randy Johnson, Steve Carlton, CC Sabathia and Clayton Kershaw — struck out more batters than Lolich, whose 2,832 still rank 23rd on MLB’s all-time list.

Twice with the Tigers, he finished in the top three in American League Cy Young voting, including a runner-up spot in ’71, when he narrowly lost to Oakland’s Vida Blue, and was fifth on ballots for league Most Valuable Player. A year later, Lolich was third in the Cy Young count and 10th in MVP votes. He was a three-time All-Star.

During the prime of his career, from 1964-76, Lolich averaged a staggering 263 innings, nearly twice the load today’s starters typically bring to an MLB rotation during a single season.

Iron man

Lolich never had a sore arm. Never had a disabled-list stint. He never underwent Tommy John surgery, the ligament-replacement procedure that was just being developed at the end of Lolich’s career and now is almost expected for a pitcher whose career spans significant years. Lolich’s secret might well have been a matter of pure physiology. And, ironically, a mishap when he was 2 years old. He was naturally right-handed but rode his tricycle into a motorcycle that toppled onto him and broke his left collarbone, at his home in Portland, Oregon.

Doctors suggested to his parents that he use his left arm exclusively as a way to strengthen bones and ligaments. It led to him throwing left-handed. And, later, to MLB grandeur.

His left arm was but an extension of a uniquely structured athlete. Lolich was 6-foot-1 and had uncanny rotation of hips that were even broader than the belly that became something of a trademark through his later big-league years. His mid-structure shifted with such ease that his arm was spared stress that came with throwing a big-league pitch — a degree of strain that has long bedeviled and betrayed pitchers not able to absorb the repetitions on which Lolich seemed to thrive.

Lolich’s ability to throw excess innings, running up absurdly high pitch counts before such data was carefully tracked or recorded, was nearly super-human.

He also had a faithful conditioning routine different from the standard ice packs almost all pitchers follow today. Lolich would stand under the hottest tolerable shower for 30 minutes after each start. His arm would be a mass of scalded-red flesh. But he never changed his postgame protocol.

Lolich, after a fabulous pitching stretch in Portland during his teen years, planned on signing with the New York Yankees, the team to which he, his dad, and uncles were devoted. The Tigers ultimately won with a $30,000 check — heavy bonus money in the 1950s — nearly a decade before MLB adopted a draft.

He climbed from one farm rung to another in those early farm seasons. But he peeved the Tigers in 1962 when he showed up late for spring training after taking a civil-service exam in Portland — a hedge against his arm breaking down and Lolich needing a new career.

He had a jagged ’62 season and, at one point, sunk so low he was ordered to Single A. No, Lolich said, not when Frank Carswell was the manager at Knoxville.

Lolich was finished with the Tigers.

Or, so he thought.

Lolich went home and began throwing for a Portland semi-pro team, a stint that exposed him to snoops for the Triple-A Portland Beavers, then a top farm team for the Kansas City Athletics. They happily would find room for a 21-year-old lefty with Lolich’s flair.

A problem for K.C. was that Lolich remained Tigers property. Jim Campbell, the general manager who doubled as Tigers emperor during his decades in Detroit, had a solution: He would lease Lolich to the Beavers. He would allow a miffed pitcher to think things over as he dueled against Triple-A hitters. It worked for all parties. Lolich, thanks to Beavers pitching coach Gerry Staley, added a sinker that would become for him the equivalent of a six-shooter, alongside a four-seam fastball, curveball, and change-up.

Lolich and the Tigers shook hands ahead of spring camp in 1963 and, by May, the Tigers had a new lefty starter.

Flirting with danger

There were other interruptions — and irritations. Some of them dangerous.

On the former side was Lolich’s annual summer 15-day obligation to the Michigan National Guard. It put him squarely in the middle of the 1967 Detroit riot, then the worst urban conflagration in United States history. He thought he’d get called up for a couple days, then rejoin the team in Baltimore. He ended up being on active duty for 10 days and missing two starts.

Lolich also fancied motorcycles. He loved commuting to Tiger Stadium on a roaring Kawasaki, which the company made sure it exploited in radio ads featuring Lolich. Campbell simmered over his best pitcher being one bad spill from baseball exile.

But he evolved into a prolific, often-powerful pitcher. He had nearly pitched the Tigers into the World Series in 1967, a bid they missed on the regular season’s last day. He had a rougher time during the magical ’68 regular season, but he settled in time for his October heroics.

That week, beginning on Thursday, Oct. 3, and ceasing, gloriously, on Thursday, Oct. 10, was dominated by a left-handed pitcher with a paunch and a punch.

He won Game 2, in which he also hit a home run, oddly the only homer of his big-league career, regardless of regular season or postseason.

“We were stunned, just stunned,” McLain said with a laugh. “He hit the dog-poop out of it.”

It was Lolich’s turn to pitch again in Game 5, that final Monday at Tiger Stadium. And he pitched another marvel — but only after Orlando Cepeda ripped him for a first-inning homer that gave the Cardinals a 3-0 lead and threatened to end Detroit’s otherwise dreamy baseball that very afternoon.

The Tigers rallied and won, 5-3, with Lolich working a final eight scoreless innings. They headed for St. Louis, where the Tigers clobbered the Cardinals in Game 6 to set up a final showdown against Gibson, who that year threw 300-plus innings, with a 1.12 ERA, and who was about to win the National League Cy Young and MVP awards.

It was a different baseball era, the late ‘60s. Starters worked every four days, rather than the five now customary. Lolich had pitched on Monday — his usual nine innings.

Even with his iron-man ways, turning around 72 hours later to make a championship-game start seemed a risk for Lolich every bit as much as for the Tigers. But this was the most important single-day baseball moment Detroit had faced since its last world championship, in the World War II season of 1945.

Mayo Smith, the Tigers manager, had seen enough Lolich phenomena to give it a try. Lolich was game.

And then he pitched the game — of his life.

“Do you think you can go another?” Smith asked of Lolich after the fifth inning, in the Tigers’ dugout that sunny October afternoon at Busch Stadium.

Lolich nodded and shrugged.

Another shutout frame through the sixth.

“Do you think you can go another?” Smith asked, his face a cringing, I-hate-to-ask testament to what was on the line.

Lolich, unsurprisingly, said yes.

Same question after the seventh. And after the eighth. And then out he strode for the ninth, after the Tigers had broken loose against Gibson with late runs to grab a 4-0 lead.

A two-out homer from Mike Shannon was the only Cardinals blow in a 4-1 triumph. Tim McCarver popped out to Freehan to end it, unleashing a statewide party that seemed, in Detroit especially, to morph into more of a ceaseless Mardi Gras. The Tigers had won their third World Series championship. There now are 10 living players from that Tigers team, according to Baseball-Reference.com, including six from that year’s World Series roster.

“Lolich was a great pitcher, teammate and champion, but he was more than that to me,” Willie Horton, one of the living players from the 1968 team, said in a statement Wednesday. “He was like a brother for over 60 years.

“I will keep the memories close to my heart and never forget the close bond we shared.”

Only 14 pitchers ever have won three games in a single World Series, and just two have done it since Lolich in 1968 ― Johnson in 2001 and Yoshinobu Yamamoto in 2025. But as Lolich liked to point out, usually with a sly grin, he started and completed all three of his, setting him apart.

Lolich’s time with the Tigers continued through 1975 when a 35-year-old pitcher still carried enormous cachet.

During the winter meetings that December, the New York Mets cornered Campbell. They wanted Lolich. They would offer a package centered on outfielder and exquisite left-hand hitter Rusty Staub.

Campbell was thrilled.

There was only one hang-up: Lolich had the contractual right to approve any deal. He was not interested in New York or the Mets. He balked. He was not leaving Detroit, his home, his wife and family, for a stint in a culture and league alien to every comfort he knew with the Tigers.

Heavy persuasion by Mets executives changed his mind.

It did not change, not greatly, his first disposition toward New York or the Mets. Although he pitched with his usual skill that season of ’76 (192.2 innings, 3.28 ERA), he clashed with pitching coach Rube Walker and with a training staff that didn’t appreciate his no-ice policy.

He had two years remaining on his contract with the Mets, but retired, just to escape the miseries there. A year later, he was free to sign a free-agent deal with the Padres. He pitched two seasons, mostly in relief, before calling it quits, for real, at the end of 1978.

Back to Macomb County, back home, Lolich, a 1982 inductee into the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame, got busy with a new life: a doughnut shop in Rochester, which he later moved to Lake Orion.

And then, to true retirement: enjoying life with wife Joyce and their daughters, with celebrity appearances, autograph shows, fantasy camps, Tigers reunions and even a book, “Joy In Tigertown,” published in 2018.

Lolich, who lived in Washington Township, approached it all with the same tranquility that seemed to mirror the serenity he showed in throwing all those baseballs by all those big-league hitters — inning after inning after inning.

Detroit News staff writer Tony Paul contributed.

Lynn Henning is a freelance writer and retired Detroit News sports reporter.