Scientists find a ‘blue hole’ so deep they can’t reach the bottom

From the surface, Chetumal Bay looks almost placid – just a wide sheet of water with no hint of drama underneath. But below that calm is Taam ja’, a massive underwater sinkhole, or “blue hole,” that’s turned into an unexpected mystery for scientists.

At first, the plan seemed straightforward: map it with sonar, get a depth, move on. Instead, the early readings created a bigger problem – what if Taam ja’ isn’t anywhere near as shallow as those first numbers suggested?

The most recent measurements point to a hole that drops far deeper than expected, and the true bottom may still be out of reach.

Taam ja’ depth is important

Blue holes can work like natural laboratories. Some connect to cave systems beneath the seafloor.

Others collect layers of sediment over time – layers that can hold clues about past storms, shifting climates, and changes in sea level.

But before anyone can start asking those bigger questions, researchers need the basics: what shape is the hole, and how deep does it actually go?

The sonar problem

Earlier sonar mapping put Taam ja’ at roughly 900 feet (274 meters). Sonar works by sending sound waves down and timing how long it takes the echoes to come back. That’s usually reliable, but blue holes can make sonar unreliable.

The water inside these holes often changes a lot with depth. Temperature and salinity shifts can bend or scatter sound waves. And if the signal bounces off a slanted wall, a ledge, or some irregular feature on the way down, it can return early.

That early sound wave return can trick the equipment into “seeing” a bottom that isn’t really the bottom.

Then there’s the shape itself. A blue hole usually isn’t a smooth, straight tube. It might tilt, pinch inward, open into a chamber, or branch into side passages.

In a shape like that, a device lowered from above might not travel straight down – and the deepest point might not even sit directly beneath the opening.

What divers saw near the top

To get a better sense of the upper portion, divers explored the top of Taam ja’ to about 98 feet (30 meters). A few meters down, the outline of the opening became easier to see, partly because the bay water above it is often murky.

They also noticed the walls weren’t uniform. In places, the material looked soft and fragile. Some surfaces were coated with biofilms – those thin, slimy microbial layers.

By the end of the dive, the walls appeared steeper, the rock seemed firmer, and the coatings were less obvious.

Measuring depth with CTD

Because sonar can be unreliable in a complex, layered environment, the research team turned to a CTD profiler. CTD stands for conductivity, temperature, and depth.

Conductivity is used to estimate salinity, temperature is measured directly, and depth is calculated from pressure.

Pressure is the key here. As you descend, pressure rises in a predictable way – about one atmosphere for every 33 feet of seawater.

That makes pressure-based depth measurements far more dependable than sonar echoes when the acoustics get messy.

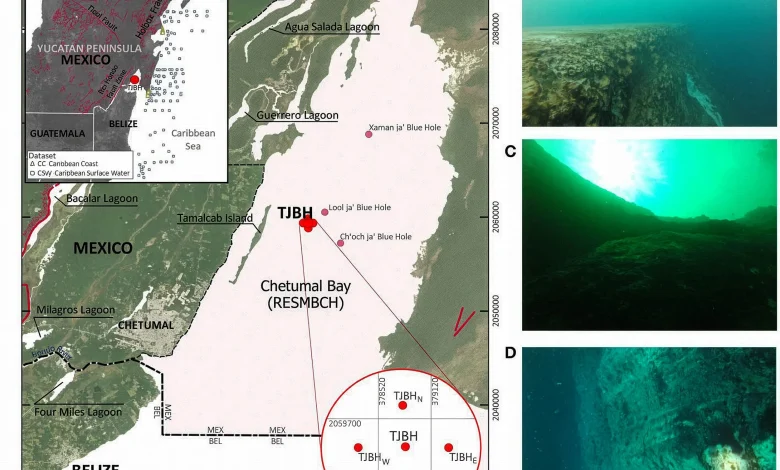

(A) Location of the Taam ja’ Blue Hole (TJBH) in Chetumal Bay, Mexico, is presented alongside the CC and CSW data regions for further comparison of water temperature and salinity conditions. Regional fracture zones and geological faults in the Yucatán Peninsula are indicated (INEGI, 2002), along with the locations of documented blue holes within Chetumal Bay. Credit: Frontiers in Marine Science. Click image to enlarge.

Two attempts to measure Taam ja’

During two separate trips in December 2023, the team anchored a boat over the hole and lowered the CTD on a long cable. The line was about 1,640 feet (500 meters) long, but the depth readings came in lower than the cable length.

That’s a sign the instrument wasn’t dropping straight down – currents can push the line sideways, and the interior of the hole might funnel the profiler along a slanted route.

In other words, Taam ja’ may tilt, widen, or open into spaces that don’t line up neatly beneath the entrance.

Even so, the results were eye-opening.

On one day, the CTD reached about 1,365 feet (416 meters) below sea level. On another, it reached about 1,390 feet (423.6 meters) below sea level – and still didn’t hit bottom.

So the safe takeaway is simple: Taam ja’ is deeper than 1,390 feet, and its deepest point still hasn’t been confirmed.

A layered world inside the hole

The CTD didn’t just record depth. It also showed that the water inside Taam ja’ is strongly layered. The instrument picked up several pycnoclines – thin bands where water density shifts quickly.

Strong density boundaries resist mixing, so the water above and below can stay separated for long periods.

Near the top, conditions looked like what you’d expect in an estuary: warmer water with lower salinity than the open ocean, which fits a partly enclosed bay receiving freshwater from land.

As the CTD descended, temperature generally fell and salinity generally rose – but not smoothly. Instead, the changes came in steps, with abrupt jumps that marked sharp boundaries between layers.

Below about 1,300 feet (400 meters), the trend shifted. Temperature began to creep upward slightly while salinity climbed even higher. That combination suggests the deeper water has a different origin – its own distinct “signature.”

When the team compared the measurements to nearby regional waters, the upper layers lined up with the bay’s mixed, lower-salinity water. The deepest measured layers, though, moved toward values more typical of Caribbean marine water.

That doesn’t prove there’s one big open tunnel connecting Taam ja’ directly to the Caribbean, but it does support the idea that the deepest water isn’t coming only from the bay above.

Next steps for the Taam ja’ Blue Hole

Geologically, the region makes this kind of complexity plausible. The Yucatán is built largely from limestone, and limestone dissolves over time, forming voids and cave networks.

Add in past sea-level changes that flooded many of those underground spaces, and you get systems where freshwater and seawater can meet and move in surprisingly intricate ways.

The next goal is a more complete map: a detailed 3D model of Taam ja’s interior, and – if possible – a confirmed bottom depth.

With that groundwork in place, researchers can start asking the deeper questions: How stable are the layers? How do oxygen and other chemicals change with depth? What kinds of microbial communities can survive in water that may remain isolated for long stretches?

For now, Taam ja’ is still partly defined by what we don’t know. We can say it’s deeper than 1,390 feet, and we can say the bottom hasn’t been found. Those facts change how scientists plan future dives, choose equipment, and design sampling.

If deeper water is entering the blue hole from elsewhere, and if the layers are staying separated, then Taam ja’ isn’t just a deep pit. It’s connected, structured, and active in ways researchers are only beginning to understand.

The full study was published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–