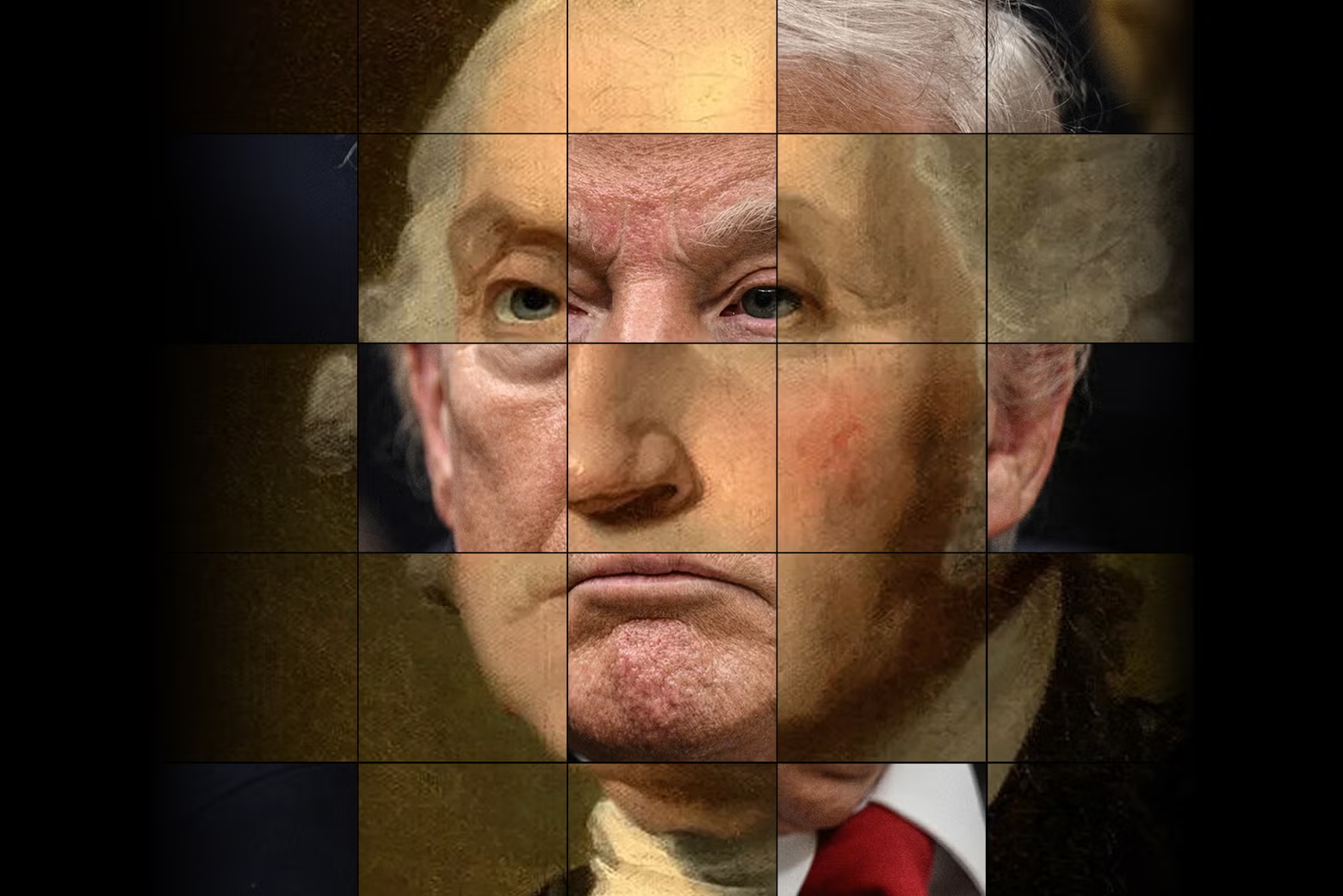

Donald Trump and George Washington Have Some Surprising Traits in Common. There’s One Gigantic Difference.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

We’re coming up on a big national anniversary, the (defiantly unspellable) semiquincentennial. To get in the spirit of things, I’ve been curled up with books about the founders, particularly George Washington, someone I became acquainted with when I wrote a book about him many years ago. But meanwhile, our current president has been honking away in the distance—a man difficult to abide and impossible to ignore.

Despite the glaring differences between Washington and Donald Trump in character, judgment, and historical significance, there are some interesting similarities. Born rich. Aggressive acquirers of real estate. Big-house guys. Thin-skinned, image-conscious. Extremely nationalistic: Trump’s message is Make America Great Again. Washington’s was … Make America.

So why will history judge them as polar opposites? In part because Washington readily and repeatedly gave up power. He did so conspicuously at the end of the War of Independence, then again after eight years as president. He lived in an era in which selflessness was considered one of the core virtues of a great leader, and at crucial moments in our history, he behaved accordingly.

Whereas Trump … well, he’s no George Washington. And he tells us so! He is instinctively royalist and brazenly self-aggrandizing. He repeatedly claims powers he does not legally have. He promiscuously puts his name on everything this side of the moon, and I probably shouldn’t even mention that particular satellite, lest he get ideas.

His decision to appoint himself as chair of the Kennedy Center was outrageous enough, but then he put his name on the place. He also put his name on the United States Institute of Peace, just a few blocks away. His face is all over D.C. now, on huge banners hanging from government buildings. He wants Dulles International Airport named for him, and also Penn Station. His open campaigning for the Nobel Peace Prize was plenty dismaying, but then he threw one of his tantrums when he didn’t get laureated and, in an official letter to the leader of Norway, demanded Greenland in compensation. At this point, we know that Trump is going to be Trump, and if anything, he leans into the narcissism, becoming Trumpier by the day. Trump has learned that his most flamboyantly selfish behavior will likely be ignored or forgiven by his base and political allies. There is no one willing to tell him that You Can’t Do This.

Our nation was founded upon the principle that power derives from the people. We don’t like despots and dictators and monarchs or anything smacking of royalty. That was why the founders were very careful when they crafted the Constitution: The president is just one branch of government, is constrained by checks and balances, and can always be given the heave-ho.

Which takes us back to George Washington. Everyone knew he was going to be the first president—he was right there in the room, presiding, when the founders drew up the Constitution. But they were taking a chance, because no one really knew what a president was. Such a thing didn’t exist anywhere in the world. George Washington had to define the role through his actions.

What modern historians know is that selflessness didn’t come effortlessly to Washington. He had to will it, in tension with his natural, human desires.

This is a subtlety of Washington that Americans weren’t taught in elementary school, and I don’t think the A.I. bots have quite figured it out. A schoolkid asking an A.I. program for help with an essay about Washington will probably get highlights of the man’s consequential life, the first-in-war, first-in-peace stuff, and perhaps learn that he was an enslaver who, like the other founders, failed to end the vile institution of human bondage. But the child is unlikely to find out what Washington was really like. Here’s what ChatGPT produced when I asked it to “write an essay on George Washington’s personality”:

George Washington was a man of great integrity, character, and leadership. His personality was marked by a strong sense of duty, humility, and selflessness. … Despite his many accomplishments and successes, he remained humble and never sought accolades or praise for himself.

Oh, balderdash. Yes, Washington was indeed a man of integrity, character, and leadership. That led him to behave selflessly at critical moments during the founding of our country. But Washington desperately wanted to be a great man, and wanted to be remembered as such. He craved the approbation (one of his favorite words) of his peers and guarded his image as though it were the front line of a war. He sought, as multiple biographers have put it, “secular immortality.”

He didn’t wander into greatness: he pursued it, willed it, achieved it. He had a “monumental ego,” in the words of historian Joseph Ellis. Peter Henriques, an admirer of Washington who has recently published two insightful books on his character, writes that Washington “was not a ‘selfless’ man or one who was simply engaging in disinterested service. Rather, a pattern emerges of a man who was deeply ambitious, massively concerned with his reputation, and in regular search of the public approbation, even as he denied such desires.” This is not revisionist history. This is the man as he really was. Washington is so tied up with the narrative of American greatness and exceptionalism that some people may think it’s wrong to probe him too deeply. Why not just salute and move on? As Alexis Coe put it in her recent biography, “We haven’t been taught to think critically about Washington.”

His avaricious acquisitions of western lands is well known and not incidental to his desire to break from Great Britain, which had tried to limit western migration. When I wrote my book The Grand Idea, about Washington and his Potomac River schemes (he thought it would surely be the great commercial highway to the West), I was a bit shocked at his imperious behavior when he traveled across the mountains into what is now western Pennsylvania and confronted poor farmers who (he alleged) were squatting on his land. He sued them. He forced them to pull up stakes. He could be pretty high-and-mighty, and certainly not exactly a small-d democrat.

And yet his drive, his ambition, his hunger for glory were essential to the enterprise of wresting the colonies from the grip of distant overlords. And his desire for secular immortality didn’t mean he was pretending to have lofty republican sensibilities. He was anti-monarchical to the core.

Washington curated his reputation and polished it for the eyes of future generations. Shortly before his death, he wrote a will that broke apart his vast estate, including more than 50,000 acres of land, and set in motion the freeing of the enslaved people under his legal control (delaying manumission until the death of his wife). These were actions very consciously taken with the eyes of history upon him. He knew that slavery would be a permanent stain on his reputation. And he was right.

Early biographers helped advance the image of a godlike Washington. Most famously, Parson Weems invented from whole cloth the story about young Washington taking a hatchet to his father’s cherry tree, then confessing to it. The early chroniclers, including John Marshall (who fought under Washington’s command and later served as chief justice of the United States), delivered to the public the kind of man that the fragile young nation desired: an unblemished father figure, preposterously virtuous.

Go the Capitol rotunda and look up at the dome, where Constantino Brumidi’s fresco The Apotheosis of Washington, painted during the Civil War, shows Washington in heaven, flanked by goddesses. You have to strain to see him, way up there, high above this mortal coil. He’s a remote figure, unapproachable. Not like us.

Cassandra Good

George Washington Had No Children. Or Did He?

Read More

Washington cared a lot about appearances and made sure that he presented himself as a formidable, dignified figure, not someone you’d slap on the back on a whim. He liked a bit of pomp and pizzazz as president. He was meticulous in ordering well-made clothes, and a “chariot” with some gilding wouldn’t be too excessive, he thought. But he had to be careful. If he acted too much like royalty, he’d get spanked by his peers and excoriated by anti-Federalist newspapers. “No Kings” was not just a protest sign in those days.

Human nature has not changed. There have always been people who desire wealth and power. They are never infallible or immune to misjudgment. What changes and evolves are the political ecosystems. Laws change, as do values, societal expectations, the means of communication, the technologies of political life. The norms. Norms can erode.

-

Pam Bondi Crashed Out for a Bizarre Reason. She’s Not Alone.

Trump, the opposite of an enigma, constantly tells us exactly who he is. He reveals this in late-night social media rants (“SEDITIOUS BEHAVIOR, punishable by DEATH!”) and unguarded conversations caught on tape (“When you’re a star, they let you do it” and “I just want to find 11,780 votes”).

He is at least consistent in his message. He tells us, over and over, This is all about me. So of course when Rob Reiner and his wife were murdered, Trump immediately said the killings were linked to Reiner’s political opposition to him. His solipsism is nonnegotiable.

Historians will have an overwhelming job of compiling and organizing the confetti of royalist declarations from this president, but let’s simplify their work a bit. The most important moment, the defining one, is obvious: Trump refused to accept that he lost the 2020 election and—another example of action defining character—urged the vice president and an unruly mob to halt the peaceful transfer of power. That’s as un–George Washington as it gets. Washington knew he was part of something bigger than himself. He had helped create a nation, but it didn’t belong to him. So after eight years fashioning the office of the presidency, he did something simple and exemplary: He went home.