Laser writing in glass for dense, fast and efficient archival data storage

Key metrics

We evaluate the Silica storage system against the following metrics:

-

Voxel quality, Q = B/nV, is an average (bit per voxel) calculated from the number of user bits, B, stored in a large number of voxels, nV. Q Qw, where Qw is total number of bits per voxel, because redundant bits are added to correct for errors. We define q = Q/Qw as the quality factor (see section ‘Redundancy optimization and error correction’). All other metrics except lifetime are dependent on Q.

-

Data density, ρ = Q/V is the voxel quality that can be stored in a volume V of glass (Gbit mm−3), where V is computed as the product of the x pitch, y pitch and the effective z pitch (that is, the total 2 mm thickness of glass divided by the number of layers written).

-

Usable capacity is the total number of user bits that can be stored in a single glass platter 120 mm square and 2 mm thick, reduced by a factor of 0.747 to account for engineering overheads, measured in TB per platter.

-

Write throughput, θ = fNLQ, where f is the laser repetition rate and NL is the number of beam lines, is the speed at which data can be written to the glass, measured in bit s−1. It is defined as a peak throughput.

-

Write efficiency, η = E/Q measures the energy consumed to write each user bit (nJ per bit). E is measured after the objective. A lower η represents better write efficiency and so is preferred as it allows more bits to be written in parallel for the same laser pulse energy.

-

Lifetime is an experimental estimate of the lifetime of the data stored in the glass (see section ‘Lifetime’).

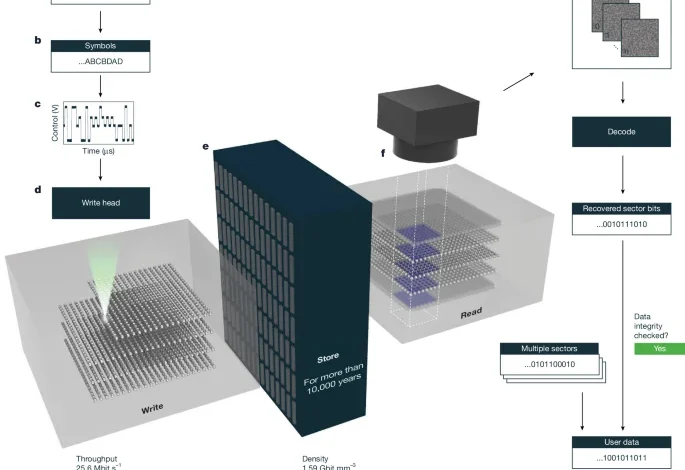

Write

Figure 2a shows the key building components of the data writing system. The source is an amplified femtosecond laser (Amplitude Systems, Satsuma HP3 with harmonic generation, 516 nm central wavelength (second harmonic), and tunable pulse duration from 300 fs to 1,000 fs). We measured the pulse duration before the objective lens using a Gaussian fit of the autocorrelator signal (APE, Carpe). The output laser pulse train at 10 MHz passes through a tunable attenuator, quartz half-wave plate on a motorized rotary stage and Glan linear polarizer.

After the attenuator, the optical configuration depends on the type of voxel being written. Birefringent voxel writing requires polarization modulation and beam splitting, the latter to generate seed and data pulses. Phase voxel writing requires only amplitude modulation.

The modulated laser pulses are collimated and incident on a self-air-bearing polygon scanner (Novanta, SA24) with 24 facets spinning at 10,000–50,000 rpm. The scanned laser pulses are directed through a custom-made f-theta scan lens (focal length = 63 mm) followed by a relay lens. This optical arrangement ensures that the pulses consistently enter the objective pupil, regardless of the scan angle.

The objective (Olympus, LUCPLFLN40X) focuses the scanned laser pulses inside the glass platter (2 mm thickness), which is mounted on an xy translation stage (PI, V-551.7D and 551.4D). The translation stage moves at a constant velocity along the x-axis, whereas the pulses are scanned along the y-axis so that we write a plane of voxels at constant depth. We choose the velocity of the stage and the spinning rate of the polygon so that the laser pulses are focused at the intended pitch, for example, about 3.57 mm s−1 and 17,000 rpm for an intended pitch of 0.5 μm × 0.7 μm in glass. The relation between the velocity, the spinning rate and the pitch is given by the repetition rate of the laser pulses, the magnification from the polygon facet to the objective lens, the number of polygon facets per rotation and the focal length of the objective lens (Supplementary Information).

The writing depth in the glass is changed by translating the objective lens in z while using an in-house-designed, motorized actuator to adjust the spherical aberration correction collar of the objective. The CMOS (complementary metal-oxide semiconductor) sensor (FLIR, GS3-U3-41C6M) captures the photoemission images during writing through the same objective as the write laser beam. The images are used for the closed-loop control to stabilize the voxel writing (for more details, see section ‘Emissions-based control of voxel writing’).

We stabilized the rotational speed of the polygon using a photodiode that detects a fixed continuous wave laser beam (632 nm, Thorlabs, PL202) reflected off the polygon facets. The beam, on a separate path from the writing laser, sweeps across the photodiode once per facet, generating 24 spikes per revolution. These spikes provide feedback to control the polygon motor speed. To account for the difference in polygon facet reflectivity, we measured the photoemission intensity from a line of voxels written with each polygon facet and use this as a calibration signal to feed in to the AOM (for more details, see section ‘Emissions-based control of voxel writing’).

The energy per voxel (EPV) is determined by measuring the average laser power after the objective lens with a thermal power meter (Thorlabs, PM101A). EPV is measured only for the strongest symbol; therefore, it represents the energy requirement before amplitude modulation. This value is used to estimate write efficiency, excluding losses from optical bench components.

Birefringent voxels are written in fused silica glass (Heraeus, Spectrosil 2000). Phase voxels are written in borosilicate glass (Schott, BOROFLOAT 33).

Writing birefringent voxels by pseudo-single-pulse regime

Between the tunable attenuator and polygon scanner, there are two key modules required for writing birefringent voxels with the pseudo-single-pulse regime: a tunable beam splitter and a polarization modulator.

Tunable beam splitter

The attenuated laser beam is split into two beams (seed and data) with either an acousto-optic deflector (AOD) (G&H, AODF 4140) or polarization grating (PG) beam splitter. The AOD splits the laser beam at an arbitrary angle and power ratio by tuning the radiofrequency signal. We typically use an energy ratio of 100:60–70 for the seed:data pulses. The PG beam splitter, consisting of a pair of PGs, splits a laser beam into two, the angle and power ratio of which can be tuned by changing the relative angle of the PGs and the polarization of the input beam (Supplementary Information). We tune the split angle between the seed and data beams to make the distance between the seed and data pulses inside the glass equal to a multiple of the voxel pitch, so that the data pulse hits the seed structure created by the seed pulse. Our best density was achieved using a spacing between seed and data beams of three voxel pitches at a voxel pitch of 0.485 μm.

Polarization modulator

After splitting, the two beams pass through a relay lens and are directed into two sequentially arranged Pockels cells (ADP, Leysop, EM200A-HHT-AR515), with a relative crystal orientation of 45°. The two Pockels cells modulate the polarization of each pair of pulses (both seed and data beams simultaneously). We write with elliptical polarization (ellipticity = 0.5) to reduce the Pockels driving voltages. We use our own custom-made high-voltage modulators to modulate the Pockels cells (200 V peak-to-peak amplitude with 10 MHz bandwidth). The polarization is unintentionally modified by some of the optical components after the Pockels cells. We compensate for this modification using a pair of wave plates after the Pockels cells, tuned so that the polarization at the objective pupil is circular when both modulators are set to 0 V.

Writing phase voxels

Between the tunable attenuator and the polygon scanner, the beam passes through a module responsible for amplitude modulation. After passing through a tunable attenuator, the beam is reduced to a diameter of 0.5 mm or less and directed through a quartz AOM (G&H, I-M110-2C10B6-3-GH26) for beam deflection and amplitude modulation. This spot size ensures the modulation rise and fall time is less than 100 ns. The AOM is modulated with a radiofrequency signal that is frequency-locked to the laser. The radiofrequency signal encodes the data and modulates the diffraction efficiency of each pulse. We use the first diffracted order for writing.

For multibeam writing, we split a laser beam from the same source (Coherent, Monaco 517-20-20, 10 MHz repetition rate and 517 nm central wavelength, 310 fs pulse duration) into four beams, each of which is modulated with its own AOM and made to propagate closely together by a beam position controller with edge mirrors. The beams are scanned with the same polygon facet and incident on a single objective lens at slightly different angles perpendicular to the scanning direction. The objective lens focuses the four pulses at different locations inside the glass. More detail on the multibeam setup is provided in Extended Data Fig. 4, and the thermal simulation methodology is described in Supplementary Information.

Emissions-based control of voxel writing

White light emission arises during writing from the generation of a dense and hot plasma during voxel formation28. The write objective is used to collect this emission in a back-reflection configuration. The emission is transmitted through a dielectric mirror (the same mirror that deflects the writing beam in the forward pass) and imaged using a tube lens and relay optics onto a camera sensor (2,048 × 2,048 pixels, 8-bit FLIR, Grasshopper3, GS3-U3-41C6M-C). The scanning line (length up to 300 μm) is magnified on the camera sensor to ensure at least 3 pixels per 0.5 μm inside the glass. A notch wavelength filter is installed to remove scattered laser light. The emission profile along the scan line is obtained by first integrating the pixel intensities vertically and then binning horizontally to obtain a 128-point signal. The sensor is rotated about the optical axis to avoid interference effects between the sensor rows and the emissions line.

The emission-based control has two aspects: offline flattening and closed-loop control. Offline flattening compensates static differences at different points in the scanning space, for example, caused by reflectivity of the polygon facets. Closed-loop control compensates dynamic differences during the writing process, for example, temperature fluctuation, by controlling the laser power with the AOM to reach a specified emission target.

The offline calibration of the non-linearity in the electronics and AOM, the spatial variation in the polygon and scan optics, and the depth-dependent variation in the objective are done by a combined procedure. The laser is set to a fixed energy just below the damage threshold, and the AOM modulation is swept from the modification threshold to maximum, forming voxels at multiple depths in the glass. Hence, for every element in depths × facets × scan angles, we have a mapping from modulation to emission. We invert this mapping using quadratic fits to obtain the dynamic modulation required to achieve a flat target emission. This is stored and then superimposed with the symbol modulation during subsequent data writing.

In closed-loop control, a target emission value is defined for each sample. This value is relative and may vary between experiments and writing systems. Writing proceeds along the x-axis in sequences called supersectors. Each supersector begins with a few pad sectors, written using only the highest amplitude symbols. These pad sectors allow the writer to measure the initial emission profile and adjust the laser power using the AOM. After each supersector is written, the writer uses the pad sectors to iteratively tune the AOM modulation until the emission aligns with the target value. This tuning process is repeated as needed. Closed-loop control resets at the start of each layer, and the camera shutter time is configured to integrate over at least one full polygon revolution to ensure consistent emission measurement.

After writing the final supersector of each layer, we measure the EPV to track the absolute energy metric, as described in the section ‘Write’. For more details on emissions-based control, see Extended Data Fig. 6.

Write conditions of data samples

Phase voxels

The write conditions for data samples are as follows: about 16–19 nJ at 1.9–0.1 mm glass depth, respectively, measured after objective; 400 fs pulse duration before the objective; 0.5 μm × 0.7 μm voxel pitch, 7 μm layer spacing and 258 layers; borosilicate glass (BOROFLOAT 33, Schott); phase voxels regime (isotropic RI change); 516 nm wavelength; NA 0.6 (40×) focusing objective (Olympus, LUCPLFLN40XRC); single-pulse per voxel at 10 MHz laser repetition rate (Satsuma, Amplitude); four levels of amplitude modulation; synchronized polygon scanning (Novanta, SA24) and XYZ (PI) media and objective translation.

Phase voxels for symbol count and modulation optimization

The conditions for symbol count and modulation optimization are as follows: about 16 nJ–20 nJ to about 19 nJ–23 nJ at 1.9–0.1 mm glass depth, respectively, measured after objective; 400 fs pulse duration before the objective; 0.5 μm × 0.7 μm voxel pitch, 7 μm layer spacing and 258 layers; borosilicate glass (BOROFLOAT 33, Schott); phase voxels regime (isotropic RI change); 516 nm wavelength; NA 0.6 (40×) focusing objective (Olympus, LUCPLFLN40XRC); single-pulse per voxel at 10 MHz laser repetition rate (Satsuma, Amplitude); 31 levels of amplitude modulation; synchronized polygon scanning (Novanta, SA24) and XYZ (PI) media and objective translation.

Phase voxels for multibeam analysis

The conditions for multibeam analysis are as follows: about 17–19 nJ at 1.9–0.1 mm glass depth, respectively, measured after objective; 310 fs pulse duration after the objective; 0.5 μm × 0.7 μm voxel pitch, 7 μm layer spacing, and 258 layers; borosilicate glass (BOROFLOAT 33, Schott); phase voxels regime (isotropic RI change); 517 nm wavelength; NA 0.6 (40x) focusing objective (Olympus, LUCPLFLN40XRC); single-pulse per voxel at 10 MHz laser repetition rate (Monaco 517-20-20, Coherent); four levels of amplitude modulation; synchronized polygon scanning (Novanta, SA24) and XYZ (PI) media and objective translation.

Birefringent voxels written by pseudo-single-pulse regime

The write conditions for birefringent voxels written by pseudo-single-pulse regime are as follows: about 22–26 nJ at 1.9–0.1 mm glass depth, respectively, measured after objective; 300 fs pulse duration before the objective; 0.500 μm × 0.485 μm voxel pitch, 6 μm layer spacing and 301 layers; fused silica glass (Spectrosil 2000, Heraeus); elongated single nanovoid voxels regime (birefringent modification); 516 nm wavelength; NA 0.6 (40×) focusing objective (Olympus, LUCPLFLN40XRC); pseudo-single-pulse per voxel at 10 MHz laser repetition rate (Satsuma, Amplitude); eight levels of polarization modulation; synchronized polygon scanning (Novanta, SA24) and XYZ (PI) media and objective translation.

Read hardware

For both birefringent and phase voxels, we read using a wide-field microscope with an sCMOS (scientific CMOS) camera (Hamamatsu ORCA Flash4 v.3.0, 2,048 × 2,048 pixels, 6.5 μm pixel size) and LED illumination. The glass is mounted in a custom-made sample holder that is mounted on a mechanical xyz stage.

The illumination, mechanical motion of the sample and the camera are all controlled by custom software developed in-house.

At write time, several fiducial markers are written into the glass at predetermined locations, and the data location is known relative to these markers. The read subsystem finds these fiducial markers and uses them to calibrate the glass position so that any track or sector can be located automatically.

To record all images for sectors in a track, we first need to find the in-focus positions of each sector. To do this, the sample is first continuously moved in the z-direction with the camera running at a fixed frame rate. We adjust the frame rate and the z velocity so that we record about 10 frames per sector, and for each frame, we compute a variance-based sharpness metric. The peaks in the sharpness metric are used to find the in-focus positions of each sector. The sample is then moved to the in-focus position for each sector in turn, and the camera is triggered to record one or more images at that position. This process is fully automated so that a user can request to read several tracks with one command. The acquired images are then uploaded to a persistent storage for post-processing and decoding. The remaining elements of the read hardware are different for phase and birefringent voxels.

Birefringent read

Our birefringent read subsystem is a custom-built wide-field polarization microscope. The light source is a Thorlabs Solis-525C LED with a central wavelength of 525 nm. The principle of reading is based on previous work39. We use a fixed linear polarizer and wave plate to generate circularly polarized light in the illumination path. The illumination light is focused onto the sample using Köhler illumination. The condenser is a 50× Mitutoyo long-working-distance objective with NA 0.55 (MY50X-805). The objective is a 40× Olympus NA 0.6 objective (LUCPLFLN40X). It has a spherical aberration correction collar that is adjusted automatically as we move in the z-direction by a custom-built motorized unit mounted on the outside of the objective. The tube lens is a Thorlabs TL180-A with focal length 180 mm. We have two liquid crystal variable retarders (LCR-200-VIS, Meadowlark Optics) in the detection path. We adjust the voltage on these retarders to set the polarization detection state.

In previous work, a fixed number of configurations of polarization states were described39. For Gaussian noise, the angular uncertainty (measured by the Cramer-Rao bound) is minimized when the states are evenly distributed around the Poincaré sphere. Therefore, we improve over previous work by arranging three polarization states at 120° intervals around the Poincaré sphere, rather than at 0°, 90° and 180°.

To read and decode voxels, we are not trying to count how many voxels are in an image; this is already known. Rather, we are trying to distinguish the symbol levels from each other. Higher NA leads to less overlap between the signals from nearby voxels and, therefore, in the presence of noise, better decoding quality.

Phase read

We use a custom-made Zernike phase-contrast microscope to read phase voxels. The light source is a Thorlabs Solis-445C LED with a central wavelength of 445 nm. As our aim is solely to distinguish between different written symbols, rather than extract quantitative phase information, we use Zernike phase-contrast microscopy33, a simple and robust qualitative method that is sufficient to render voxels clearly visible against the unmodified glass background.

A known limitation of Zernike phase contrast is its inherently poor optical sectioning, which introduces increased axial cross-talk between adjacent data layers compared with birefringent voxel readout, in which no phase masks or apertures are placed in the objective or condenser pupils. We mitigate this effect by capturing two images per data layer. This method exploits the fact that, using this imaging modality, voxels exhibit intensity oscillations and contrast inversion when scanned through the focus, on the length scale of a few μm. Background features from out-of-focus regions, in contrast, remain largely unchanged within this range. We, therefore, acquire one image at the z position at which voxel contrast is maximal, and a second image several μm deeper in the glass, at which voxel contrast is both reduced and inverted. The relative strength and sign of the two peaks depend on focusing conditions and can be adjusted using the correction collar. Using this dual-image approach, we were able to reduce the BER by a factor of two compared with using a single image per layer.

The illumination objective is a Thorlabs MY20X-804 with an annular amplitude mask. The objective lens (Olympus, LUCPLFLN40XPH) has NA 0.6 and a working distance of 2 mm with a phase ring. It has a spherical aberration correction collar that is adjusted automatically as we move in z by a custom-built motorized unit mounted on the outside of the objective.

Lifetime conditions

We used a macroscopic measurement approach to evaluate the durability of phase voxels, tracking their thermal erasure in representative platters containing hundreds of data-carrying tracks. This method exploits the 3D periodicity of the written structures: when a collimated light beam traverses the modified glass, it undergoes diffraction at discrete angles, providing a clear and unambiguous optical signature of voxel presence. We found in numerical simulations that, for phase voxels, the diffraction efficiency at a given order is a periodic function of the average RI modulation, and approximately quadratic in our regime of small index changes. This means the diffraction efficiency serves as a convenient proxy that we can monitor to probe the thermal erasure of voxels during annealing experiments.

Samples were annealed in a furnace (Carbolite GERO, LHT 6/30) at four elevated temperatures (440 °C, 460 °C, 480 °C and 500 °C), each in four successive 1-h steps. At each annealing step, we measured the absolute diffraction efficiency of a 405-nm laser beam (HÜBNER Photonics, Cobolt 06-MLD 405) passing through modified glass, using a pair of photodiode power sensors (Thorlabs, S121C) to record the incident and diffracted power. The measured decay curves of diffraction efficiency η compared with time t were then normalized and fitted with a stretched exponential of the form \(\eta =a\,\exp (-{(t/\tau )}^{\beta })\), where a is a dimensionless scaling factor, β is a dimensionless stretching factor and τ corresponds to the characteristic 1/e decay time for the diffraction signal. A single value of β was used to fit data for all temperatures. The best value was found to be 0.427. The fitted time constants were then used to determine the activation energy using the Arrhenius equation \(1/\tau =A\,\exp (-{E}_{{\rm{a}}}/{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T)\), where A is the pre-exponential factor, Ea is the activation energy and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The best fit for the activation energy was found to be 3.28 eV.

Machine learning model

We use machine learning to infer symbols from sector images. The decoding pipeline contains four steps: pre-processing, symbol inference, symbol-to-bit mapping and error correction (Fig. 3c). For pre-processing, we find the boundaries of each sector within each image by using a small amount of known data written at the edge of the sector (Extended Data Fig. 7a).

Our model is a CNN that decodes one sector at a time. It is trained on large quantities of sector images and their corresponding ground truth symbols. The use of a CNN leverages our ability to generate large quantities of training data by writing and reading known data patterns. It takes as input a stack of images that contain information about a sector and outputs a 2D array of symbol probabilities for each voxel in that sector. The symbol probabilities are then mapped to bit probabilities according to the modulation scheme used during writing. This design allows us to account for contextual spatial information through optical scattering, out-of-focus light on the reader, and interference within and across layers. We also provide two additional 2D positional encoding channels to account for possible xy-dependent image aberrations (for example, vignetting and depth-of-focus variations). Each sector image provides at least 4 × 6 pixels per voxel. The CNN applies a series of convolutions, nonlinear activations and downsampling operations to extract features relevant to symbol classification from the input image at different resolutions. Extended Data Fig. 7 shows the model architecture used for the phase voxel results in section ‘Silica system analysis’. Although we explored other model variants, all architectures remained convolution-based.

As mentioned in the section ‘Reading and decoding data’, for phase voxels, the optical PSF is elongated and therefore information is distributed across images acquired from multiple z positions in the glass. We, therefore, feed in images acquired above and below the sector of interest to the neural network to decode that sector. We call the additional images context images. Including more context images can improve decode quality, although the impact diminishes with an increasing number of context images and is dependent on the z pitch between voxel layers. This effect is shown in Extended Data Fig. 7d.

With our current model configuration, the receptive field of a given voxel prediction is approximately 32 voxels × 32 voxels × 3 voxels, or 16 μm × 22 μm × 21 μm in (x, y, z) around the voxel.

We split the dataset into training and validation sets, and process the training data in non-overlapping batches (typically 16 sectors). For each batch, we perform a forward pass to obtain predictions, then compute the categorical cross-entropy loss between the predicted symbol probabilities and the ground truth symbols, averaged across all voxels in all sectors in the batch.

This scalar loss is backpropagated to compute gradients, which are used to update the model parameters according to the optimizer settings. Each update is a training step. We repeat the training steps until all the sectors in the training set has been used, which we count as one epoch. We use Adam optimizer40 with a learning rate of 3 × 10−4, which decays by 10% every 50 epochs.

At the end of each epoch, we evaluate the model on the validation set using mutual information, averaged across all voxels. Training continues for 150 epochs, and we retain for inference the model that achieves the highest validation mutual information.

Redundancy optimization and error correction

Silica, similar to all data storage systems, requires error correction to ensure data integrity despite raw bit errors. We wish to measure the density of user data that can be stored once error correction is allowed for, and to choose error correction parameters that maximize this effective density.

It is not adequate to estimate density using raw BER because bit errors are not perfectly uniformly distributed and the overhead needed to correct bit errors is substantially larger than the fraction of bit errors themselves37. We now describe how we estimate the density of user data using an error correction scheme.

We choose LDPC codes37 for error correction within sectors and an erasure code that spreads k sectors of data over n sectors so that as long as any k of the n sectors are perfectly decoded, the user data can be reproduced18. The density of user data is then the raw data density, multiplied by the product of the LDPC code rate and the erasure code rate k/n.

We use the bit probabilities coming from the CNN decoder as input to the belief propagation algorithm used in LDPC decoding37. This is a form of soft-decision decoding, which is more efficient than hard-decision decoding, and it allows us to use the full information available from the symbol inference algorithm.

We chose the 5G wireless telephony standard LDPC error correcting code41 because it is designed to work with a wide range of coding rates. In the telephony application, transmitters can send either a very few or very many redundant bits at code word generation time depending on their estimate of the channel quality. At the receiver, redundant bits that are not present are entered into the belief propagation network with exactly balanced probability between one and zero (no information), and the error recovery code is designed to proceed to a solution, if possible.

The variable LDPC code rate and consequent erasure code rate together form a Pareto front. The point that maximizes the recoverable information stored, the useful density of the media and the cost efficiency of the writer is the maximum of the product of the two metrics, and we use this metric for our experimental workflow, and for our definition of quality factor. For product design, engineering margins would be included, and a different point on the Pareto front may be chosen based, for example, on the desirability of reading the n sectors of a redundancy group; the details are not provided in this paper.

We now describe our procedures for determining the Pareto front. First, we write a piece of glass with all sectors containing random test data at a 0.5 rate, that is, half data bits and half redundant bits in each sector. On reading, for each sector, we obtain the bit probabilities from the machine learning symbol inference, and then iteratively attempt an LDPC decode with fewer and fewer of the redundant bits, until we find the minimum number of redundant bits that allows successful recovery of that sector. This value gives the highest code rate at which this sector could have been reliably written and read. The error rate, and hence code rate, varies over the sectors in the platter, and we can plot the code rate against the fraction of sectors that were recovered at that code rate, forming a Pareto front.

An example is shown in Extended Data Fig. 1g. However, for simplicity, we sometimes plot the quality factor against code rate, as in Fig. 3d, in which case the optimal point is the one with the largest vertical axis value.

Extending binary Gray codes

It is common in coding to use a binary Gray code42 to map user data bits into symbols, in which each symbol is represented by a binary code word that differs from the previous one by only one bit. This minimizes the BER in noisy channels, as adjacent symbols are most likely to be confused due to noise. Binary Gray codes are typically defined only for powers-of-two symbol counts (for example, assigning the two-bit sequences 00, 01, 11, 10 to four consecutive symbols, respectively). Gray codes also exist for non-binary encodings43.

However, to maximize the capacity of the Silica channel and simultaneously use binary LDPC error correction, we sometimes need to consider non-powers-of-two symbol counts, yielding a binary encoding. We call an encoding method (A, v, b)-encoding, if it adopts an alphabet with A symbols per voxel, and assigns b-bit sequences to groups of v voxels. An (A, v, b) scheme assigns b bits (2b patterns) into v voxels (Av patterns), where Av = 2b + Δ, with Δ as small as possible, ideally 0. The goal is to maximize the channel use by transmitting at a rate \({\log }_{2}({A}^{v}-\varDelta )/v\) close to the channel capacity. A small A underuses the channel, whereas a large A increases the SER, requiring significantly more FEC overheads for practical decoders. If possible, we also like to maintain the Gray property: if we mistake a single symbol for its neighbour, then this flips only one bit.

Consider, for example, a Silica channel with a capacity of 1.5 bits per voxel. A naive (4, 1, 2)-encoding uses a four-symbol alphabet with one symbol per voxel, allowing each voxel to transmit two bits, but with a high SER. A better approach is the (3, 2, 3)-encoding, which uses a three-symbol alphabet and assigns 3-bit sequences to pairs of voxels. This means each voxel on average transmits 1.5 bits, which is at the channel capacity. For this encoding, Δ = 1: of the nine possible pairs of symbols, we are using only eight.

We identified a perfect Gray coding for alphabet sizes of A = 3 × 2i, and a near perfect coding for A = 5.

Symbol selection optimization

The need to optimize the number of symbols and their energy modulation was motivated in the section ‘Optimizing parameters at each pitch’. Our method for symbol selection models the glass storage system as a communication channel whose task is to transmit a modulation, denoted as Y, for each voxel, through the processes of writing, reading and decoding. The goal is to identify an optimal set of modulations that maximizes the amount of information we can transmit through this channel.

We begin by determining the initial range of modulations by identifying the minimum modulation required to modify the glass, Ymod, and the maximum modulation for a target emissions value (and which does not damage the glass), Ymax.

Next, we define a set of M candidate modulations, uniformly spaced across Ymin to Ymax, where M is high enough to sufficiently sample the modulation space. In typical experiments, M = 31.

A training sample is then written, in which each voxel is assigned a modulation randomly selected from the M candidates. The sample comprises thousands of sectors to ensure sufficient data diversity for model training.

A regression model is trained to predict the modulation for each voxel. We call the predicted modulation \(\widehat{Y}\). At inference time, the model outputs a probability distribution over \(\widehat{Y}\) for each voxel, say \({P}_{v}(\widehat{Y})\). This probability distribution represents the estimate of the modulation of the model that was used to write each voxel.

We then group together the \({P}_{v}(\widehat{Y})\) distributions by their modulation Y, giving us \(P(\widehat{Y}| Y)\). \(P(\widehat{Y}| Y)\) represents the model’s estimate of the modulation that was used to write all voxels of a given known modulation Y. This captures the model’s representation of the channel. These distributions are shown in Fig. 4b.

Finally, we perform an optimization (using Sequential Least Squares Quadratic Programming) over the aggregated distributions to select a subset N out of M of modulations. This involves simulating decoder performance, including LDPC error correction, for subsets of modulation (varying both the number of symbols in the set and the modulation chosen for each symbol in a set) and estimating the mutual information between decoded and transmitted data. The optimal subset is chosen to maximize this mutual information. We can then use this optimal subset of N symbols to write user data.