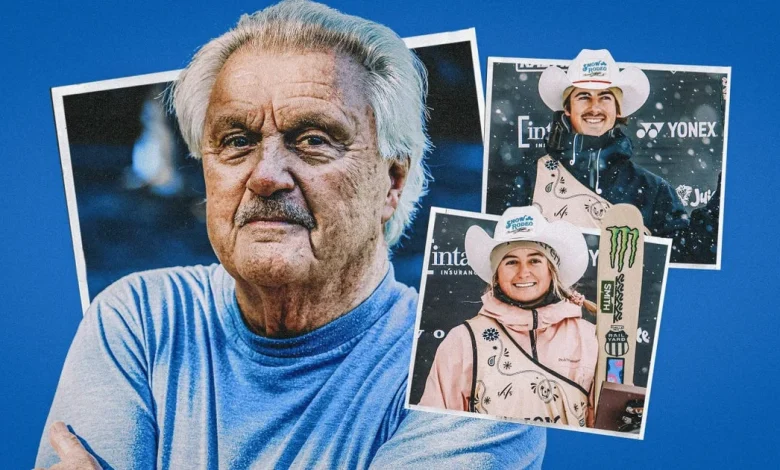

What’s it like to have two grandchildren in the Winter Olympics? Let John Irving tell you

BORMIO, Italy — Every now and again, Birk and Svea Irving, the brother-sister Olympic skiing duo, receive text messages requiring time and attention. They unlock their phones, open their message apps, click “Grandpa.” Then thumbs scroll.

“Complete paragraphs, all spaced out,” Birk Irving says. “Grammatically, the best text messages you’ve ever seen.”

Recently a correspondence came via email, one written in that familiar style. The concrete nouns, the spirited adjectives, the rhythmic repetition. First, a congratulations. Making the Olympics, as Birk did in 2022, is incredible. But making the Olympics together as siblings? That’s a storybook, one that should be cherished. The note told Birk and Svea that everything they’ve accomplished is a product of ambition and focus colliding into a perfect storm of realized talent. They read that they should be proud of that, and that their grandfather wished he could be in Italy to see them compete. He said he was in awe of who they are and what they do.

John Irving wrote the email from his home office in Toronto. At his desk, in a flannel shirt, hunched over his laptop, one he mostly resents for its “technical challenges.”

Now 83, the great American author is somewhere in his postscript. Nearly five decades since “The World According to Garp” gave rise to a career of global literary influence, one with an oeuvre including the likes of “The Cider House Rules” and “A Prayer for Owen Meany,” Irving still rises to write every day. He is not retired because he cannot retire. “If you’re a writer,” he says, “what excuse do you have to stop?” Irving’s 16th novel, “Queen Esther,” published last year.

Even at this stage, Irving’s public profile very much remains his identity. He can’t attend the Olympics because traveling to the Italian Alps and asthma complications aren’t a great mix. So instead he’ll be in Vancouver, sitting on stage at the Jewish Book Festival as a featured speaker.

He will be tired. Men’s and women’s qualifying in freeski halfpipe begins Thursday, with Birk riding at 1:30 a.m. local time in Vancouver, and Svea taking her turn at 10:30 a.m. The men’s finals, when Birk will try to improve on his fifth-place finish in 2022 should he qualify, is on Friday, while the women go Saturday. Irving has a “tech savvy” personal assistant, Finlay, who will be charged with finding a stream of the action. Irving says Finlay will “keep me connected to what’s happening in Livigno.”

Birk Irving came fifth at the Beijing Olympics four years ago. (Maddie Meyer / Getty Images)

When we think of Olympic journeys, grandparents are often among those faces in the crowd spanned by cameras. Smiling faces. Stock characters in uplifting stories. The roughly 1,600 athletes in these Olympics translates (very loosely) to about 6,400 grandparents.

It’s hard to imagine what it must feel like. Seeing your living legacy is one thing. Seeing that legacy in the Olympics is something else entirely.

“I remain astonished by them,” Irving said recently from his home in Toronto. “By their sweet dispositions, and the level of friendly normalcy they’ve always had, knowing, as I do — and I say this in a positive sense — their fanatical desire to always be training, to always wanting to compete and improve.”

Irving once dreamt of being a world-class athlete, one good enough to wrestle at the Olympic level. This was a lifetime ago.

Raised by his mother and stepfather in New Hampshire in the 1950s and 60s, he developed a borderline obsession with sport. He loved the meritocracy of effort and achievement; that, as he once wrote, “you had no one to blame but yourself.” Irving wrestled collegiately at the University of Pittsburgh and in grad school at the University of Iowa, wringing everything out. He has said his athletic career, like his writing career, “was one-eighth talent and seven-eighths discipline.”

Two of Irving’s children, sons Colin and Brendan, followed their father onto the mat, finding more success in New England prep wrestling than John ever did, but Brendan found himself drawn more to the solitude of a ski slope.

Having grown up skiing in Vermont, Brendan enrolled at Western Colorado University, “where you go to ski, and maybe get a degree in your spare time.” He graduated, got his EMT license, and joined a local ski patrol, caring little about the pay and more about the access to slopes. Once Brendan met his wife, Stephanie, a former Alpine skier at the University of Washington, the course was set. A teaching job for Stephanie in Winter Park, Col., resulted in Brendan Irving landing a job on the ski patrol at a local resort.

Birk and Svea, born three years apart, grew up on the hills of Winter Park Resort. Brendan and Stephanie encouraged Alpine skiing. Such hopes were feckless in the face of young Birk discovering the halfpipe. He fell in and never got out. His sister followed.

There they remained, all the way to medals in the Winter Youth Olympics (Birk, 2016) and the World Junior Championships (Svea, 2017); years and years spent riding 22-foot high walls, touching the sky, and returning (hopefully) intact. Both Birk, now 26, and Svea, 23, have seen the hard side of freeski halfpipe. Svea has dealt with a bum knee all year and sounds like a retired offensive lineman when rattling off her injury list.

Watching Birk and Svea grow up, mostly from afar, first in Vermont, then in Toronto, John Irving has long been mystified. Just like your grandfather would be.

“To be honest with you, whether I’m watching them on TV or on a live stream, or if I’m there on the ground freezing to death, I’m terrified of the halfpipe,” Irving said. “It is a level of risk in skiing that I am not accustomed to. It would never occur to me to go into a halfpipe.”

Svea Irving is set to compete in qualifying for the women’s freeski halfpipe final on Thursday. (Maddie Meyer / Getty Images)

Brendan was roughly 9 or 10 when “The World According to Garp” changed the family’s trajectory. Birk and Svea were roughly the same age when they began to realize their grandfather was not a typical grandfather. The family would leave its thousand-square-foot house in Winter Park and visit grandpa in Vermont. “And it would be, ‘Hey, dad, grandpa has a bigger house than we do.’” Birk especially loved the huge wrestling gym in the basement. “I’d practice for like eight hours a day, just for fun,” he says.

As the kids came to realize who their grandfather really was, John Irving also began to realize who these kids were. He was always charmed by their idyllic childhood — free to frolic around a ski resort, growing up in some sort of winter sports Disneyland.

It would have been easy for Birk and Svea to take it all for granted. It would have been easy to spend teenage years ski-bumming around. But they didn’t. They not only worked, they worked when no one was looking. Like grandpa said in that letter — none of this is coincidental, none of it accidental.

“They always had it,” John Irving said. “They were willing to block out all the distractions and do it again and again and again. Repetition. I’ve always thought that, if nothing else, writing and rewriting is a dedication to a repetitive process. Any craft, any sport — the more you repeat it, the better you get at it. But you have to do it.”

Svea Irving pictured competing during the women’s freeski halfpipe final at the U.S. Grand Prix at Copper Mountain Resort on December 17, 2022. (Tom Pennington / Getty Images)

A trademark of Irving’s writing is the power of what goes unsaid — that which the reader comes to understand later. Like what’s in the name.

John Irving was born John Wallace Blunt Jr., after his biological father, a World War II pilot who divorced John’s mother during her pregnancy. While Irving later learned that his father had wanted to be in his life, but his mother refused the request, he nevertheless grew up resenting his biological father. That massive burden was eased by his stepfather, a man named Colin Irving, who John has always said was one of the most impactful people in what’s been a staggering life.

His birth name was changed to Irving in 1948, when he was 6.

Seventy-eight years later, the Irving name will be announced at the Olympics, not once, but twice.

“All the credit goes to Brendan and Stephanie,” Irving said.

And to Birk and Svea. The two have made their own names, so much so that acquaintances meet them, then learn who their grandfather is. One of Birk’s coaches is reading “The Last Chairlift,” Irving’s 2022 novel that centers around skiing. His girlfriend is listening to the audio version of “The Cider House Rules.”

It bothers Irving that he can’t be in Livigno to see the kids compete. Each is considered a serious medal contender, but such results are neither here nor there. No matter how they perform, Birk and Svea will give their grandfather an incredible gift.

They’re giving him something to cheer for.

They’re giving him something to watch.