Kirstin Downey: New Details Surface About Pearl Harbor Attack And Aftermath

Even as Honolulu’s annual remembrance of the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor tees up again this weekend, starting with a Rosie the Riveter meet-and-greet Friday, new details about the original assault and its aftermath keep coming to light.

In the past year, World War II historians have uncovered a previously unknown Pearl Harbor Navy logbook and advanced new research on prisoners who were held at Honouliuli Internment Camp.

Meanwhile, as the last of Pearl Harbor’s aging service members pass from the scene, a new set of veterans is coming to the fore as local historian Jessie Higa reveals the hidden story of the true last survivors — children of service members who were living on Hawaiʻi’s military bases at the time of the attack and became traumatized eyewitnesses to shocking scenes of destruction that have gone on to haunt their adult lives.

And one of the last deep secrets of the World War II deception was at last exposed this year when the granddaughter of German immigrant Otto Kuehn published a tell-all confessional about how her Nazi family, living in luxury in Hawaiʻi, had profited by selling information about American troop movements to the Japanese government. During his lifetime, Kuehn vehemently denied he was a spy, but now his granddaughter has acknowledged that the charge was true.

After the passage of so many years, skeletons are coming out of the closet.

Ideas showcases stories, opinion and analysis about Hawaiʻi, from the state’s sharpest thinkers, to stretch our collective thinking about a problem or an issue. Email [email protected] to submit an idea or an essay.

‘Lost To Time’

“We’re finding things now that have always been there, but inaccessible to the point that no one knew it was there, no one had any interest in it, maybe,” Higa, the children’s chronicler, told Civil Beat. “So now what I’m finding out is 84 years later, we are still unearthing stories and history that were just lost to time.”

In August, the National Archives in Washington, D.C., announced the recovery of a long-lost logbook from Pearl Harbor, complete with handwritten entries of troop ship activities from March 1941 through June 1942.

It details some of the events that occurred in the harbor on Dec. 7, 1941: “0755 Japanese aircraft and submarines attacked Pearl Harbor and other military and naval objectives …”

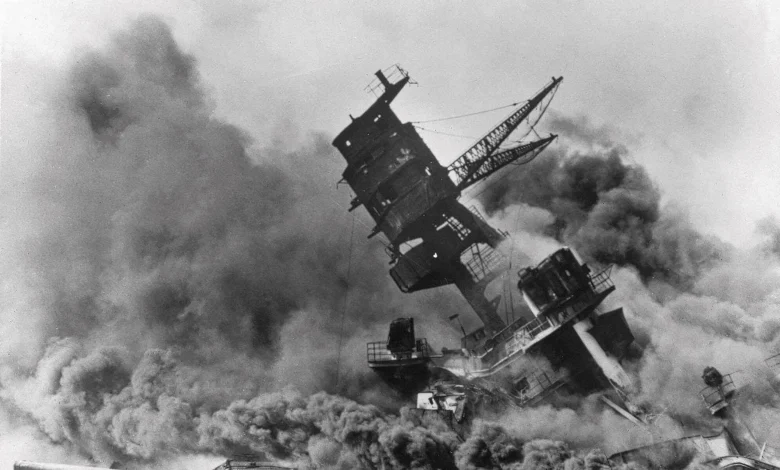

American ships burn during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. (Associated Press)

It also contains details of a lesser-known second attempted attack by the Japanese on March 4, 1942: “0045 received report of unidentified planes approximately 50 miles away. … three shots and whistling projectiles heard …”

That attack ran into poor visibility and did little damage.

The logbook survived because, sometime in the 1970s, Oretta Kanady, a civilian employee at Norton Air Force Base in San Bernardino, California, spotted an intriguing bound volume dumped in the trash bin at work, pulled it out and took it home, according to the Washington Post. Fifty years passed. Kanady’s son decided to try to sell it, but when the National Archives learned of the logbook’s existence, they nixed the prospect of a sale and claimed it as part of the national patrimony.

Kanady’s son ruefully told the Post that all he got in exchange was a National Archives T-shirt.

In September, a lecture series at Honouliuli Internment Camp, best known for housing Japanese-Americans unfairly held as potentially treasonous, unveiled new research showing that many residents of the camp were actually Koreans whose country had been colonized by the Japanese and who were detained by American forces that encountered them in battle. Another large group held at the camp were from Okinawa, which had been annexed by Japan in 1879.

Jessie Higa, left, greets Shirley Waldron Nied in 2016 outside the home where Nied lived as a child. (Defense Visual Information Distribution Service)

Child Witnesses

Higa, a historian and tour guide, has been studying the Pearl Harbor attack since 1991, when she worked as a park ranger at the Pearl Harbor National Memorial. For decades she has examined the lives and experiences of the veterans who served at the bases that bore the brunt of the attack, which left more than 2,400 dead. But as that generation dies away, Higa’s research has shifted to studying the children of service members, many of whom were living on base that day. It is not known how many of them still survive.

Families living on Ford Island confronted a ghastly panorama as oily smoke billowed across their entire field of view, exposing the surreal hellscape of battleships sinking only hundreds of feet away. Sailors were flailing in the water, some badly burned. Others were entombed underwater.

Higa said many of the children witnessed soldiers and sailors wounded, dying or dead. Teenage girls were pressed into service nursing the injured. Corpses were laid face down on a nearby lawn. Some children were haunted by the memories, she said.

Higa has collected the story, for example, of Shirley Waldon Nied, a Honolulu resident who was 5 years old and living at Hickam Field when it was attacked. In an interview in November 2024, Nied described how she woke up to the “sound of bombs” and roused her parents from bed. She looked out the window and saw a Japanese plane flying so low she could see the pilot’s face. Her father, also a pilot, rushed out of the house to join his men in defense of the airfield.

The family was subsequently evacuated from their home. For decades, Nied was too traumatized to return to the house.

Higa continues to compile information from people like Nied and is preparing her research for publication.

The view from the house in ʻAiea Heights where Otto Kuehn may have spied on Pearl Harbor. (Kirstin Downey/Civil Beat/2025)

‘Family Of Spies’

Kuehn’s book, meanwhile, “Family of Spies,” has finally been released for sale.

After Civil Beat published my column about Kuehn’s upcoming book in July, the family of Stanley Henning reached out to say that they believe their house in ʻAiea Heights may have been another of Otto Kuehn’s spy posts.

The house, high on a hill overlooking Pearl Harbor, has a commanding bird’s-eye view of the entire base complex. With binoculars, it would have been possible to see battleships enter and exit the port, and, on a clear day, to even be able to count how many people were on the deck.

Otto Kuehn added dormer windows to his house in Kailua to signal Japanese submarines off the coast. The house and windows are still visible behind the walls. (Kirstin Downey/Civil Beat/2025)

When Henning bought the house from a U.S. Army colonel in the mid-1970s, the seller told him that Kuehn had spent time there and had been able to scrutinize naval activity from an upper lanai — information he might have been able to communicate later to his Japanese handlers via coded message.

Did Otto Kuehn live or spend time at the house in ʻAiea Heights? Maybe. Census records for 1940 show Kuehn and his family living in Kailua.

But one other detail seems to corroborate their account: A German beer stein was pressed into concrete in a lower stairwell, accompanied by this number etched into the cement: 1941.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign Up

Sorry. That’s an invalid e-mail.

Thanks! We’ll send you a confirmation e-mail shortly.