What does a debt crisis look like in the G10?

It’s a commonly held view that the hurdle for debt crises in advanced economies is very high. That’s because monetary policy credibility – even if it’s under assault – is still considerable, which means central banks can print money and buy bonds when yields spike without de-anchoring inflation expectations. I’m not a fan of this view for two reasons. First, when public debt gets high enough, bad shocks can cause spikes in yields because markets – rationally – anticipate bigger deficits and even more debt. If central banks systematically cap yields in bad shocks, that removes any incentive for governments to bring public debt down and pushes central banks further and further down the fiscal dominance rabbit hole. This will – sooner or later – de-anchor inflation expectations. Just because it hasn’t happened yet doesn’t mean it won’t. Second, even if central banks can cap bond yields, they can’t simultaneously prevent the currency from falling. If risk premia are artificially suppressed in the bond market, they’ll just show up in a depreciating currency. The idea that you can cap bond yields is therefore a dangerous illusion. Debasement catches up with you one way or another.

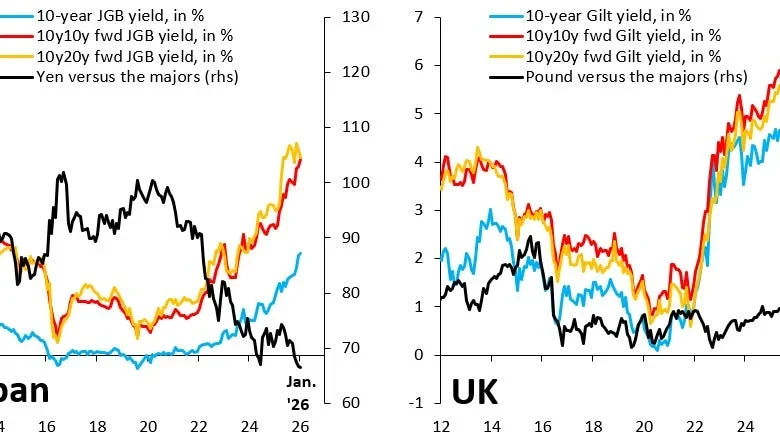

Perhaps the most important point to make is that we’re already seeing low-grade debt crises in a bunch of places. The left chart above shows the trade-weighted Yen versus its G10 peers (black line) along with the 10-year Japanese government bond (JGB) yield (blue line), the 10y10y forward JGB yield (red line) and the 10y20y forward JGB yield (orange line). The 10y10y forward yield is backed out from 10- and 20-year JGB yields and reflects what markets price for the 10-year yield in 10 years’ time. The 10y20y forward yield is backed out from 20- and 30-year JGB yields and reflects what markets price for the 10-year yield in 20 years’ time. The really worrying thing in this chart is that the Yen has fallen materially, even as JGB yields have risen to unprecedented levels. That’s a sign that a debt crisis is underway. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) is capping yields via still very large gross purchases of JGBs. As a result, the risk premium that would show up in the bond market is showing up in the currency.

The right chart shows the same thing for the UK. Importantly, the scale on the left and right axes is exactly the same, so that moves in the trade-weighted Pound and in Gilt yields can be compared to Japan. The rise in UK yields is bigger than for Japan, which has helped keep the Pound comparatively stable. In the UK case, risk premia have been allowed to manifest in the bond market, shielding the Pound from the kind of depreciation that’s befallen the Yen. But even if the Pound is more stable, the basic dynamic is the same: a low-grade debt crisis as higher yields put the government under severe pressure.

The truth is that there’s a lot more crises like Japan and the UK. In the Euro zone, there’s Italy, Spain and – increasingly – France. The only reason these three don’t look as bad is because they share a currency with Germany. Germany’s low debt is helping to stabilize the Euro for now, but even here – as Germany embraces higher deficits and more debt – the writing is on the wall. The bottom line is that debt crises in the G10 are very much possible. In fact, we’re already seeing them play out in real time.