Pistons trash-talking their way to the top with new Dawg Pound mentality

For one day, the Detroit Pistons chose not to be a basketball team.

Despite an early-January skid, head coach J.B. Bickerstaff had canceled practice. The Pistons had succumbed to a couple of losing teams on the road in the Utah Jazz and LA Clippers. In other scenarios, maybe Bickerstaff runs them until their legs, no matter how young, turn into noodles.

Instead, he tested another tactic.

Bickerstaff invited the players to the UCLA campus, where they convened on the soccer pitch. The Pistons split into teams, coaches included.

On that day, they traded an orange ball for a black-and-white one, which didn’t stop them from acting like the same rugged, won’t-shut-the-heck-up, surprising leaders of the Eastern Conference. Win or lose, and it’s usually lose, no one enjoys facing Detroit, where basketball looks more like monster trucks.

No matter what sport they play, the Pistons act like the Pistons.

Starting center Jalen Duren, a gentleman always built like a superhero and now starting to ball like one, had never played soccer until that day at UCLA. The players competed barefoot, much to the reservations of the team’s medical staff. No one got hurt, at least not physically.

On one play, Duren found himself in the open field with a chance to score the first goal of his life. His brain is so far removed from soccer jargon that he later called the would-have-been score “a bucket.” With his best bud and fellow enforcer, Isaiah Stewart, manning the goal, Duren unleashed a line-drive kick. Stewart leaped in the air and swatted away the shot.

“Get that s— out of here!” Stewart screamed at Duren. “It ain’t happening! It ain’t happening!”

The famed amateur soccer gods must have scripted this moment. Cade Cunningham might be the Pistons’ MVP candidate, but Duren and Stewart are the embodiment of the team’s tenacity.

Years ago, Duren, Stewart and then-Pistons assistant coach Drew Jones would yell “Dawg pound!” at each other whenever one of the two big men would make a hustle play, set a hard screen or accomplish any other feat they considered dirty work. The tradition continued away from games. They’d greet each other in the hallway or the film room by shouting the phrase. Just for the fun of the bit, Jones went on Etsy and made a $30 chain for Stewart and Duren. At the bottom of it was a bulldog with bones in its mouth.

A sub-organization, the Dawg Pound, had formed inside the Pistons. The prerequisite to get in was simple.

“You gotta do dawg s—,” Duren said in a recent conversation with The Athletic.

The institution still lives strong. “Dawg Pound” is now painted above Stewart’s and Duren’s lockers in Detroit’s home arena.

But the Dawg Pound extends beyond the court. Stewart wasn’t even supposed to be in goal when Duren kicked that shot toward the net. He had begun the match in the field with assistant coach Luke Walton playing goalie. But midgame, Stewart went to Walton and insisted they switch.

Like Duren, Stewart wasn’t an experienced soccer player, which was apparent in his performance.

“I was worried I was gonna check somebody,” Stewart told The Athletic.

Stewart’s flagrant fouls and ejections are the mainstream hits, the actions that frame his reputation, but his best work (and true value) comes on his indie records: his rim protection and relentless defense. Off the floor, his teammates swear by him, but they also witness a screw loosen any time he enters competition.

OK, so he’s a disaster at soccer and surrounded by his friends. Does he check the smallest guy? The biggest guy?

“I check the nearest guy,” Stewart clarified.

It was probably best for everyone that Stewart pulled himself from the field. After all, he won’t change who he is. Nor will Duren. Nor would a new member of the Dawg Pound, second-year wing Ron Holland. Nor would Cunningham or defensive menace Ausar Thompson.

And nor would the Pistons want any of them to do so.

This is what Bickerstaff prefers: Everlasting competition. It’s why in the middle of an uncharacteristic skid, one of the NBA’s youngest teams pushed aside basketball and instead leaned into the group’s personality.

It’s why Duren, whose ferocity has helped him to a breakout season, is still talking about that almost-goal. The 22-year-old is posting career-best numbers on a career-best team trying to win its first playoff series since 2008. But that’s not enough.

“I wanted to f—— win,” Duren said. “It just is what it is, bro, and then we talk s— about it after.”

Pistons teammates Tobias Harris and Jalen Duren. Harris sets up beach volleyball tournaments for the team in the summer. (Nic Antaya / Getty Images)

Over the summer, Pistons players met at Wayne State University in Detroit for a two-hand touch football game that became too contentious for most guys on the squad to relive.

“Everybody was talking s— to everybody,” Holland said.

Eventually, the game just sort of ended. Because it had to.

Duren and Stewart say Holland only found that football game to be so heated because he hasn’t been around long enough to know better. The rest of the team points to summertime beach volleyball tournaments, which veteran forward Tobias Harris organizes in San Diego, as the scene of truly out-of-pocket moments.

The entire organization competes in volleyball — from players to coaches and even the PR staff.

Stewart, one of the NBA’s grandiose intimidators, was picked near last while choosing teams this past August, which set the tone for the day.

“That’s a f— you,” Stewart said. “So, you’re already coming in very competitive. … You just wanna bust some ass. So now every game, you’re coming in like, ‘Bring your ass over here,’ and we’re just jawing between every point.”

The Pistons trash-talk on the court. On the field. On the beach. When they play video games. During shooting competitions after practice.

“It’s in everything, bro,” Duren said. “It could be getting food.”

If one guy’s meal looks more delicious than another’s, cover your ears.

Every great Pistons champion has won while exuding the same style. There were the “Bad Boys” of the 1980s and early ’90s, who bashed their way to two NBA titles. There were the mid-2000s Pistons who reached six straight Eastern Conference finals and won a championship on the backs of defense and toughness.

Only a couple of seasons ago, with many of the same characters already in Detroit, this group lost 28 consecutive games. Last season, the Pistons shocked the league, reeling off 44 victories and losing in a hard-fought first-round playoff series. Now, they own the NBA’s second-ranked defense and sit at 30-10, 4 1/2 games better than the second-place Boston Celtics, who the Pistons face Monday night.

Cunningham is revving toward All-NBA First-Team status. Thompson and Holland are hounds. Harris, Duncan Robinson and Caris LeVert are dependable vets. On any given night, an unexpected young guy would win them a game. Daniss Jenkins could get hot, or Marcus Sasser could nail three 3s in three minutes. Stewart is making his clearest case ever for an All-Defensive Team appearance.

But the greatest development of the season has been the Dawg Pound’s other leader, Duren, a former first-round pick who relied on natural ability over his first three professional seasons but now has emerged as an All-Star hopeful and one of the league’s most improved players.

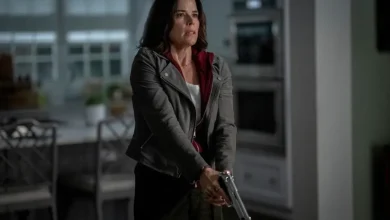

The Pistons have adopted a Dawg Pound mentality this season, thanks in part to Jalen Duren and Isaiah Stewart. (Courtesy Detroit Pistons)

The Pistons could not hit a jumper the day before that soccer match. They went 0-for-11 from deep during the first half of an ugly loss to the Clippers. Other than during a third-quarter run from Cunningham, they couldn’t create clean shots. Kawhi Leonard torched them for a career-best 55 points.

And yet, even on their off nights, the Pistons operate differently than they have in years past — especially Duren.

Midway through the game, with the Clippers on a heater, Duren pulled Thompson to the side to chat about pick-and-roll coverages. “I can show more on that screen,” he told Thompson. The two youngsters discussed how to perfect their strategy, as if they’d been doing this for millennia.

Later, after committing a sloppy foul, he went to LeVert, nearly a decade his elder. “I’m gonna stop reaching,” Duren told him.

“He knows when he messes up now,” said Pistons assistant Vitaly Potapenko, who played for 11 years in the NBA and now works closely with Duren. “He’s coaching himself.”

The brute center’s scoring has skyrocketed this season. For the first time, he’s the definitive second option behind Cunningham. But his largest leap has come on the other side of the court.

During the beginning part of his career, even as recently as last season, opponents leaned on an obvious game plan against the Pistons: Bring Duren into space. He might have been a chiseled giant in danger of concussing himself on the arena ceiling any time he jumped, but his team defense was wonky. He’d run to the wrong places or not recognize an opponent’s plays. He’d turn one way, then another and then another until he watched the enemy score. In moments, he looked like he was impersonating the final scene of “Inception.”

For the first time in his life, Duren couldn’t overpower any person in front of him. He had been a highly ranked high school recruit, a dominant down-low force and lottery pick. But when he first entered the league, he was the youngest player in it. NBA athletes are experts at identifying and attacking vulnerabilities.

Eventually, Duren hit a breaking point.

“No more of this being-picked-on s—,” he said.

He studied film on his defense this past summer. He worked with Potapenko and Bickerstaff on verticality around the rim, keeping his arms straight in the air while contesting guys who jumped into him, which would help limit fouls. Throughout last year, he started to notice in the moment why his mistakes were happening, though he couldn’t always fix them immediately.

“Once you understand what your weaknesses are, you’re able to work on them,” Duren said. “Rome wasn’t built in a day.”

Duren changed his body, getting leaner in the offseason to help with his mobility and flexibility. Not only is he smarter when opponents pull him away from the paint, but he improved manning centers who can pop to the 3-point arc; it’s also not nearly as easy to drive by him.

The Pistons have worked with their big men not necessarily on shot blocking, but more on what they call “changing and challenging” shots. If a dribbler infiltrates the paint only to try a layup or dunk, the goal isn’t to get a hand on the ball. It’s to make that player uncomfortable enough to force a miss. Stewart, who can rattle off his advanced rim-protection metrics to the decimal, has become obsessed with this concept. Duren has followed suit.

The Pistons allow only 62 percent shooting at the rim, the third-lowest figure in the NBA, according to Cleaning the Glass. Much of that is because of the Dawg Pound duo. Stewart, even though he stands at only 6-foot-8, has become one of the world’s most effective shot alterers. Duren is fouling less and deterring more.

“He realized he was damn near 7-foot-2,” Thompson said.

Duren, whose biceps are the size of thighs, might be the only player listed at 6-foot-10 who could be accurately described that way. The realization comes at an opportune time for the soon-to-be restricted free agent. Duren was eligible for an extension this past summer, but he and the Pistons were so far apart on numbers that the two sides never even got into negotiations, league sources said. Duren sought a max contract. Detroit didn’t believe doling out so much money before its starting center proved himself more would be prudent.

Duren will enter the upcoming summer with a stronger argument for a payday — not just because of individual improvement, but also because of how he fits into an up-and-coming culture.

Isaiah Stewart has found a gear with the Pistons this season. (Nick Cammett / Getty Images)

Duren and Stewart have a new favorite bit.

The two remain the arbiters of who gets in and who stays out of the Dawg Pound. Holland earned entry purely on vibes. He’s not a shooter and defends as if he doesn’t feel pain. They have denied membership requests but, out of respect, won’t say to whom — with one exception, Thompson.

Years ago, Cunningham created his own Pistons club, Big Guard University (BGU), which has since somewhat disbanded. Thompson, another defensive menace who thrives on physicality and often guards the other team’s best player, yearns for Dawg Pound acceptance, but Duren and Stewart tell him he can be only “part-time.”

Sometimes, the 22-year-old, who on top of being an all-defensive talent also has true offensive potential, gets too skilled for their liking.

A couple of weeks ago, Duren jabbed Thompson for being a part of Cunningham’s BGU, not the Dawg Pound. He couldn’t possibly be a member of both.

“I haven’t even heard of (BGU),” Thompson quipped, insisting he was the fourth member of the Dawg Pound.

He made his Dawg Pound case, smirking but frustrated with his friend, who he knew was only messing with him to inspire a reaction. Well, Duren got one.

“I’m the biggest dawg,” Thompson retorted in jest. “Sometimes you wanna exile the biggest dawg.”

Thompson won the interaction with the one-liner. Duren broke character and burst out laughing. Of course, the comment didn’t change Thompson’s part-time status. Nothing could. As long as Thompson’s denied entry bothers him, Duren and Stewart will be too entertained to grant him admission.

But Duren is reaching an uncomfortable reality, too. He still fights for rebounds. Defensively, he’s better and certainly grittier than ever. And yet, Duren — who could, of course, never actually be described as a guard — is inching closer to Big Guard University than he might care to admit. He’s averaging six more points per game this season than he did in 2024-25. And he’s not just a rim-diving center anymore.

For the first time in his career, he’ll bring the ball up in transition. He sets screens for Cunningham, rolls to the paint, receives bounce passes, then attacks the hoop or creates corner 3s from there. His passes are ambitious. He’s added a bevy of moves around the basket and a reliable midrange shot.

He locked in this summer on balance and pivots. Setting a wider base after he picks up his dribble allows him to stay centered.

His face-up game has transformed. Never before has he put the ball on the ground so often. The Pistons average 1.194 points on passes, shots, turnovers and fouls directly out of his drives, not just the highest number of his career but also 17th out of 200 qualifiers in the NBA, according to Second Spectrum. Keep in mind, that’s a list including some of the league’s premier on-ball talent, such as reigning MVP Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, three-time MVP Nikola Jokić and two-time MVP Giannis Antetokounmpo.

And yet, Duren doesn’t seem concerned about banishment to the land of Thompson.

“I’m still all about the dirty work,” he said. “It’ll never change.”

He said his favorite type of play isn’t one of his jumpers or even a planet-shaking dunk. It’s when the Pistons defense forces a shot-clock violation.

“That s— is good,” Duren said, rubbing his palms together as if he had some unhealthy relationship with the sound of a buzzer.

“S— like that is just … I don’t know,” he said. “It just does something for the whole team.”

Such is the Duren way. And such is the way of the Pistons, who brought together naturally competitive people and watched them trash-talk each other to the top.