Tommy Lee Walker Declared Innocent 70 Years After His Execution

(Dallas, TX — January 21, 2026) Today the Dallas County Commissioners Court declared Tommy Lee Walker innocent of the 1953 rape and murder of Venice Parker, for which he was wrongfully executed 70 years ago. Mr. Walker was 19 at the time of his wrongful arrest and was executed less than three years later. After a years-long joint reinvestigation by the Dallas County District Attorney’s Conviction Integrity Unit, the Innocence Project, and the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project (CRRJ) at Northeastern University School of Law, it was concluded that, “Mr. Walker’s arrest, interrogation, prosecution, and conviction were fundamentally compromised by false or unreliable evidence, coercive interrogation tactics, and racial bias.”

“The court’s declaration today provides some semblance of belated justice to Mr. Walker’s legacy, and to his son, our client Edward Smith,” said Chris Fabricant, one of Mr. Smith’s Innocence Project attorneys. “Mr. Smith has carried the generational trauma of the irreparable injustice his father faced at the hands of the State. Acknowledging what we know to be truth — that false evidence, misconduct, and overt racism led to the execution of an innocent man — albeit 70 years later, is essential to the integrity of our legal system, the historical fabric of this country, and most importantly it is an acknowledgment of the unspeakable burden Mr. Smith and his family have carried for decades. We are thankful to District Attorney Creuzot and the Dallas County Commissioners for their willingness to formally recognize this gross and unforgivable miscarriage of justice.”

“At the end of the day, our criminal justice system must address its fatal errors, no matter how long ago they occurred,” said Northeastern Law Professor Margaret Burnham, CRRJ director and co-counsel to Mr. Smith. “This is the thrust of all our work. Clearing Mr. Walker’s name acknowledges him as a legally cognizable being, entitled — even after death — to justice, brings a measure of peace to his loved ones, and salutes those who, 70 years ago, fought to obtain justice for him — and for themselves. This case reminds us of how much must still be done to map the lethality and legacy of Jim Crow terror.”

Mr. Fabricant and Professor Burnham met in 2022 to discuss the case, and over the last three years, dozens of Northeastern Law students and staff conducted meticulous historical research, uncovering evidence of constitutional violations, coercive interrogation tactics, and racial injustice that permeated every aspect of Mr. Walker’s prosecution over 70 years ago.

A Racially Charged Manhunt

In September 1953, the racially segregated city of Dallas was in the midst of a public panic, searching for a “Negro prowler” who was reportedly breaking into homes and sexually assaulting women in the night. The attacker was described, primarily by white women, as a large Black man who was sometimes undressed. At the height of the scare on Sept. 30, Venice Parker, a white store clerk and mother of a young son, was raped and stabbed while waiting at a bus stop on her way home from work.

Bleeding profusely from a gash to the neck, Ms. Parker was found by a passerby who drove her to nearby Love Field Airport. Multiple witnesses testified that, by the time she arrived, she was unable to speak due to her injuries. However, the police officer who first arrived on the scene, a white man, claimed to have heard Ms. Parker say before her death that her attacker was a Black man. This officer’s single statement prompted police to believe Ms. Parker’s assailant and the city’s prowler were potentially the same Black man. There was no other evidence.

A Coerced False Confession

With no real leads nor any forensic evidence to test, law enforcement rounded up and detained hundreds of Black men for questioning — but failed to make progress on identifying a suspect for Ms. Parker’s murder. After four months of an unsuccessful investigation, an “unsubstantiated tip” came in identifying 19-year-old Tommy Lee Walker as a suspect. The tipster would later sue the police department for reward money he never received in exchange for the information. With no leads and mounting public pressure to solve the crime seen as the climax to the 18-month “Negro prowler” scare, police honed in on Mr. Walker.

From the moment of his arrest, Mr. Walker — who had no prior criminal record — insisted that he was innocent and could prove that he did not commit this crime. At the time of Ms. Parker’s attack, Mr. Walker was at his girlfriend’s bedside as she went into labor with his only son, Edward Lee Smith. Mr. Smith was born a few hours later at the local hospital. This was corroborated at trial by ten witnesses who were with Mr. Walker and the mother of his child in the hours leading up to Mr. Smith’s birth. But this carried little weight in Jim Crow Dallas.

Mr. Walker was interrogated for hours by notorious Homicide Bureau Chief and one-time Ku Klux Klan member Will Fritz and Dallas District Attorney Henry Wade, who oversaw 20 proven wrongful convictions of innocent Black men. Over several hours of interrogation, officials lied to Mr. Walker about existing evidence and threatened him with the electric chair. Under unimaginable pressure, Mr. Walker signed two written “confessions.” The first included factual inaccuracies that made the confession implausible. The second, which Mr Walker signed and then immediately recanted, was “fixed” by police to fit the details of the crime.

Modern social science research shows that the tactics used to interrogate Mr. Walker created a coercive environment that was ripe for generating false confessions. “We now know, through decades of research and wrongful convictions, that the tactics used against Mr. Walker — threats of the death penalty, isolation, and deception, as well as the blatant racism in this case, increase a person’s stress and mental exhaustion, placing them at significant risk of falsely confessing during police interrogation,” said Lauren Gottesman, one of Mr. Smith’s Innocence Project attorneys. “Nearly a third of all wrongful convictions that are uncovered with DNA evidence are the result of false confessions — far from an anomaly. We’ve seen that play out in countless cases like those of the Central Park Five — now known as the Exonerated Five — and the Englewood Four.”

Highly Unreliable Eyewitness Identifications

The only evidence the State had against Mr. Walker, other than the coerced false confession, was the testimony of two eyewitnesses who purported to place Mr. Walker near the scene during Ms. Parker’s attack, but did not witness the actual crime. Importantly, these two eyewitnesses only identified Mr. Walker as the man they saw months prior, momentarily, at night, from their moving vehicles, after his image was widely publicized in the media as the “confessed killer.”

We know now, from scientific research and numerous exonerations, that unreliable eyewitness identification contributes to an overwhelming 63% of the Innocence Project’s 254 wrongful conviction cases.

In this case, the witnesses who claimed to have seen Mr. Walker months prior, were both white, had been driving their cars at night when they allegedly saw him, and recalled passing an unremarkable, unknown man — all considered “estimator variables” that negatively impact an identification’s reliability. Additionally, witnesses who incidentally encounter an image of the suspect prior to an identification procedure may “unconsciously transfer” that individual to the role of the perpetrator in their memory, as in this case.

“One of the most sensational trials in the history of Dallas…”

Mr. Walker had no chance at trial. In addition to the underlying racism animating the entire investigation and prosecution, the trial was riddled with prosecutorial misconduct. Although Mr. Walker was represented by famed NAACP civil rights lawyer William J. Durham, and had overwhelming support from Dallas’s Black community, the jury was composed of 12 white men — a clear violation of his constitutional right to a jury of his peers. Decades later, it was proven (and acknowledged by the U.S. Supreme Court) that the Dallas County prosecutor’s office under District Attorney Wade had an explicit practice of excluding racial minorities from juries and threatening to terminate prosecutors who did not follow instruction.

During the reinvestigation of this case, it became clear that District Attorney Wade engaged in significant misconduct. First, he violated Brady, meaning he failed to turn over potentially exculpatory evidence to the defense, despite having a constitutional obligation to do so.

Second, he engaged in highly prejudicial misconduct during Mr. Walker’s trial that undoubtedly swayed the jury. For example, when questioning Mr. Walker in court, District Attorney Wade repeatedly made reference to unreliable and inadmissible evidence.

And, in flagrantly inappropriate conduct, District Attorney Wade personally took the witness stand on rebuttal and testified to his own personal belief that Mr. Walker was guilty. He then re-assumed his role as lead prosecutor in the case and, during closing arguments, told the jury that he’d happily “pull the switch” on Mr. Walker himself. Such actions would warrant a mistrial in a court today.

In a matter of hours, Mr. Walker was found guilty and sentenced to death, leading nearly a thousand people to gather outside of the courthouse in support of his innocence. Indeed, the NAACP together with local churches and the local YMCA, continued to support Mr Walker’s innocence, raising funds and petitions to try to prevent the execution of an innocent man — to no avail.

Mr. Walker’s case is historical, but every aspect that led to his unjust execution pervades the criminal legal system today. Nationally, Black men continue to be wrongfully convicted of capital crimes at disproportionate rates, especially in cases with white victims. According to a 2022 report by the Death Penalty Information Center, Black people are about 7½ times more likely to be wrongfully convicted of murder in the U.S. than are whites, and about 80% more likely to be innocent than others convicted of murder.”

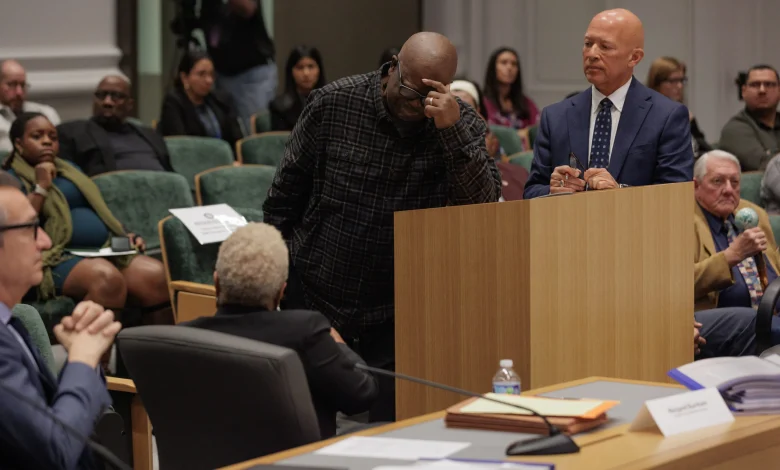

Mr. Smith said he holds the memory of his father dearly, despite only having met him once, as a two-year-old. “It was hard growing up without a father,” he said. “When I was in school, kids talked about their dads, and I had nothing to say. This won’t bring him back, but now the world knows what we always knew — that he was an innocent man. And that brings some peace.

Mr. Smith is represented by M. Chris Fabricant, Director of Strategic Litigation and Lauren Gottesman, Senior Staff Attorney at the Innocence Project; and Margaret A. Burnham, Director of the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project (CRRJ) at Northeastern University School of Law and Alex Stein, Program Director and Staff Attorney at CRRJ.

###

The Innocence Project works to free the innocent, prevent wrongful convictions, and create fair, compassionate, and equitable systems of justice for everyone. Our work is guided by science and grounded in anti-racism.