Emerald Fennell’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ is objectively not Wuthering Heights

The rumours are true about writer/director Emerald Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights.”

First off, no, that’s not a typo. The “adaptation” of Emily Brontë’s 1847 “romantic” novel literally has quotation marks in its title — a stylistic choice, the movie’s media team is quick to note, that should always be maintained when reporting on it.

It’s meant to be a pointed reference — a nod by Fennell to the fact that this is not a normal adaptation. Instead, it’s a re-creation of memory, a stylized evocation of an experience the Saltburn director had reading the book as a starry-eyed fourteen-year-old. The result is a dreamlike, visually stunning — if emotionally stunted — re-interpretation of the doomed love between brooding, hunky orphan Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi) and the beautiful, mercurial estate master’s daughter, Catherine (Margot Robbie).

Which would be an impressive swing if the changes to the source material were written with any intention of reinventing the story for modern day, instead of — at best — misreading what the book was trying to say, or, at worst, turning Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” into something that isn’t Wuthering Heights at all.

WATCH | “Wuthering Heights” trailer:

Sadly, it often feels like the latter. Like in many of Fennell’s other works (anyone heard of her Bad Cinderella Broadway adaptation?) she seems less interested in translating Brontë’s story than in performing hollow provocation with it. For example, the rumour is also true that the movie begins the way you’ve heard: A nameless man has been hanged in a town square, as children point and laugh at a certain … visibly swollen appendage, and a group of onlookers excitedly gyrate below him.

Fans of the actual Wuthering Heights are free to scratch their heads at this point, given that nothing even approximating this scene crops up in the book’s opening pages. Though if scratching is your default response to baffling left-field narrative turns, you may want to make sure your nails are trimmed. If not, watching Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” will likely lead to a brain injury.

But the changes to Emily Brontë’s classic novel go far beyond the surface level. Most egregious to many is the casting of Elordi in the first place, given that the original character is described as not “a regular Black,” but as looking “as dark almost as if it came from the devil,” who at one point even bitterly wishes he had “light hair and a fair skin” like his more attractive rival.

Fennell is far from the first to cast a white actor in the role; everyone from Laurence Olivier to Ralph Fiennes have played him in the past. But as intentionally ambiguous — and even now, academically unsure — as Brontë left it, a background perceived as something other than typically white was almost definitely intentional: an immediate and intractable distinction of class that, at least in Heathcliff’s view, positions him lower on England’s social ladder.

A ladder he is thereafter consumed with not just climbing, but with pushing others down. And it’s a change that Fennell tellingly removed in order to cast, as she later said, the character she imagined when she read it.

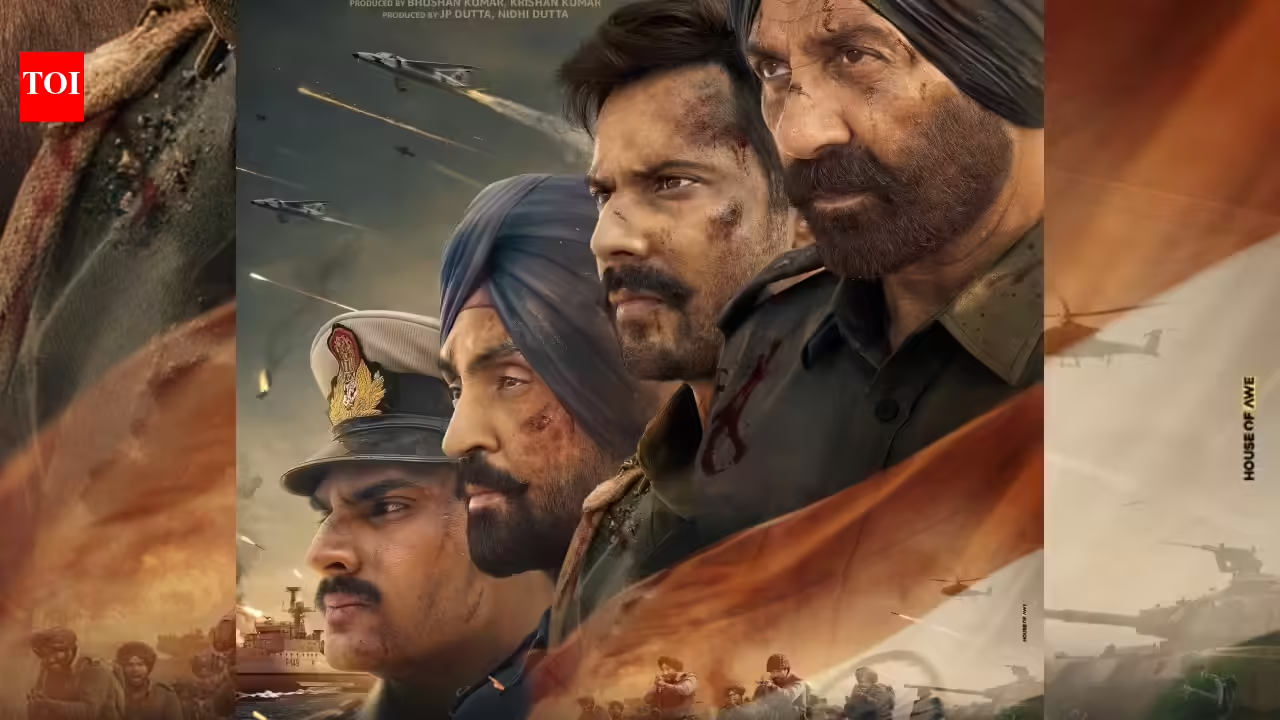

This image released by Warner Bros. Pictures shows Elordi in a scene from ‘Wuthering Heights.’ (Warner Bros. Pictures/The Associated Press)

After a few more superfluous changes, we seemingly jump right into what is similar about Fennell’s version. Namely, a dirt-covered child scooped up by a sympathetic farmer, brought home to be raised alongside that man’s daughter, Catherine, and housekeeper, Nelly (Hong Chau). In the decades that follow, the adopted boy, Heathcliff, and his newfound sister become violently obsessed with one another, pulling everyone around them into a chaotic tempest of woe, vengeance and blood.

This is really the first, and most major problem with “Wuthering Heights.” Though a version of that relationship takes place in the book, both its framing and primacy of place in the narrative are wildly different. Taking up roughly one-third of the novel, the book’s affair exists more as an inciting force for the rest of the plot and its message — explaining how and why the broader pursuit of revenge begins.

Blown up romance

Fennell instead blows that section up to obscene proportions, turning their doomed love into the focus instead of character background. Like in past versions, the rest of the story is effectively cut in half. And here, everything after their initial meeting is either completely changed or reduced to an overly maudlin, soap-opera version of the original.

This is not inherently a bad thing. The closeness of an adaptation to its source material shouldn’t be how you judge its success. Famously, O Brother Where Art Thou adapted Homer’s Odyssey without its writers or directors ever having read it. And while the first film adaptation of Alan Moore’s Watchmen was criticized as a soulless, shot-for-shot remake, Damon Lindelof pitched his later acclaimed HBO series — drastically different, though drawn from the same source material — as a “remix.”

So Fennell’s quotation mark conceit is just the latest entry in a long line of creatives trying to sidestep the complaints of a fandom obsessed with the sanctity of their media. But the difference here is intent. When Romeo and Juliet was remade as a zombie movie in Warm Bodies, the central theme of love stymied by a cultural barrier was still there. When Robin Williams took on an office worker version of Peter Pan in Hook, the question of what it means to grow up remained central.

Hong Chau appears as Nelly in a scene from ‘Wuthering Heights.’ (Warner Bros. Pictures/The Associated Press)

But when Fennell came to Wuthering Heights, it feels like she was uninterested — to the point of negligence — about the message that Brontë was trying to convey. The concept of rigid social hierarchies and ascending them in order to subjugate others is abandoned. Brontë’s lifelong obsession with death as a comforting escape is minimized to nearly nothing. Then the integral portion of the story dealing with the family’s next generation is wholly cut, virtually removing the entire purpose of the novel in the first place.

And, most egregiously, Fennell’s entire interpretation of the “love story” at its core comes off as more or less invented. Her insistence on stubbornly recreating her teenaged, romanticized interpretation of the novel becomes an exercise in pointless indulgence. After an inexplicable character introduction where he professes his undying desire to protect Cathy as a child — something nowhere near the character of Brontë’s novel — Heathcliff is transformed.

He goes from a sociopathic monster who dreams about murdering infants and painting houses with blood into a swoon-inducing object of desire. Fennell turns him into an infinitely immature depiction of an “I can fix him” hero who towers over ahistorical costumes and set design more reminiscent of Tim Burton than Britain.

From that, she turns a Romantic era-influenced story, itself in no way a romance, into something closer to Pride and Prejudice meets Fifty Shades of Grey. As a filmic oddity, it does make for an interesting invention. But stylized to the point of camp, it doesn’t make a good movie.