Predicting onset of symptomatic Alzheimerʼs disease with plasma p-tau217 clocks

Study participants

The STROBE requirements for an observational study were followed. Research participants were included who had been enrolled in previously described studies of memory and aging at the Knight ADRC16 or the ADNI13. Both cohorts consisted of community-dwelling older adults, including participants with and without cognitive impairment, who were followed longitudinally with standardized clinical and biomarker assessments. Sex was self-reported by participants in both cohorts. The Knight ADRC cohort is focused on longitudinal characterization of preclinical AD and the transition to symptomatic AD. ADNI was initiated in 2003 and represents a collaborative effort between public and private sectors, with Michael W. Weiner serving as the principal investigator (https://adni.loni.usc.edu/). The primary goal of the ADNI has been to test whether serial imaging scans, other biological markers and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of early AD.

All protocols were approved by the Washington University in St. Louis institutional review board (Human Research Protection Office) and by the local institutional review boards at each participating ADNI site. Written informed consent was obtained from every participant or, when appropriate, from a legally authorized representative.

Plasma biomarkers

Plasma was collected as previously described in the Knight ADRC16 and ADNI46,47 cohorts. Plasma %p-tau217 was measured by C2N Diagnostics with a liquid chromatography−mass spectrometry (LC−MS)-based assay32. The plasma %p-tau217 measure was calculated as p-tau217 concentration divided by non-phosphorylated tau217 concentration times 100 and is also described as the percent phosphorylation occupancy27. The Fujirebio Lumipulse G assay for p-tau217 and Aβ42 was run in singlicate with research-use-only commercially available kits on a Fujirebio Lumipulse G1200 analyzer at the Indiana University National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias Biomarker Assay Laboratory (NCRAD-BAL)23. The Janssen LucentAD Quanterix and ALZpath Quanterix p-tau217 assays were run in duplicate on a Quanterix Simoa-HD-X analyzer at the Quanterix Accelerator Laboratory. Additional details are included in the study methodology report, available in the ADNI database (https://adni.loni.usc.edu/).

Clinical and cognitive assessments

Participants underwent clinical assessments that included a detailed interview with a collateral source, a neurological examination of the participant and the CDR48. Individuals with CDR = 0 were categorized as ‘cognitively unimpaired’. Individuals with CDR > 0 were categorized as ‘cognitively impaired’; this group includes individuals with mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Individuals with clinical features consistent with cognitive impairment caused by AD (for example, most commonly, insidious onset, slowly progressive decline and early amnestic impairment but also including logopenic aphasia, posterior cortical dysfunction or dysexecutive presentations) were considered to have an AD syndrome1,33,34,35. Individuals with a primary clinical diagnosis that did not include AD (such as Parkinson disease dementia and vascular dementia) were considered to have a non-AD syndrome. The assessment of clinical syndrome was made by experienced clinicians who were blinded to biomarker results, and determinations were based solely on clinical presentation and established diagnostic criteria and were recorded as the primary clinical diagnosis1,33,34,35.

Symptomatic AD was defined to align with the established guidelines for clinical diagnosis of symptomatic AD: cognitive impairment with an AD syndrome in the context of biomarkers, indicating the presence of AD pathology1,35. The onset of AD symptoms was defined as the first clinical assessment when initially cognitively unimpaired individuals with positive AD biomarkers (based on estimated %p-tau217) were found to be cognitively impaired with an AD syndrome. Furthermore, AD symptom onset was applied only to individuals who were cognitively impaired with an AD syndrome at their last assessment—that is, if an individual had transient cognitive impairment but returned to cognitively unimpaired or had a non-AD diagnosis at their last assessment, the earlier impairment was not considered to be the onset of AD symptoms.

For longitudinal visualization and analysis, participants were categorized based on their cognitive status at each assessment and final diagnostic outcome relative to estimated %p-tau217 positivity timing: (1) cognitively unimpaired at the assessment; (2) AD syndrome/biomarker positive: cognitively impaired at the assessment with a diagnosis of symptomatic AD at their last assessment and symptoms starting after %p-tau217 positivity; (3) AD syndrome/biomarker negative: cognitively impaired at the assessment with a diagnosis of symptomatic AD at their last assessment but symptoms starting before %p-tau217 positivity; and (4) non-AD syndrome: cognitively impaired with a non-AD diagnosis at their last assessment.

Amyloid and tau PET imaging

Amyloid and tau PET imaging was conducted as previously described23. A mesial-temporal meta-region of interest (ROI) that included the entorhinal, parahippocampal and amygdala regions was used to assess early tau pathology (Tearly) with a corresponding positivity threshold of 1.328 standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) derived from Gaussian mixture modeling using the mean plus 2 s.d. of the first component23. A temporo-parietal meta-ROI that included the superior temporal, cuneus, inferior-superior parietal, inferior-middle-superior temporal, isthmus cingulate, lateral occipital, lingual, posterior cingulate, precuneus and superior marginal was used to assess late tau pathology (Tlate) with a corresponding positivity threshold of 1.224 SUVR, using a similar approach for identifying the threshold.

Cohorts

For analysis of variance in the rate of change in plasma %p-tau217, participants were included who had two or more %p-tau217 values at least 1 year apart. For development of clock models, the cohort was restricted to individuals who had two or more plasma %p-tau217 values between 1.06% and 10.45% at least 1 year apart. For models of age at AD symptom onset, individuals were included who were (1) initially cognitively unimpaired (CDR = 0), (2) subsequently developed cognitive impairment (CDR > 0) with an AD syndrome after estimated plasma %p-tau217 positivity and (3) were cognitively impaired (CDR > 0) with an AD syndrome at their last assessment. For visualization of predicted AD symptom onset as a function of estimated age at plasma %p-tau217 positivity, all individuals or individuals who were cognitively unimpaired at baseline were included.

Statistical analysis

Development and validation of plasma %p-tau217 clock models

Clock models refer to mathematical transformations that convert biomarker levels (for example, plasma %p-tau217) into disease time (estimated years since biomarker positivity), enabling temporal staging of AD pathology progression. This approach first identifies periods of consistent biomarker change and then aligns data relative to time since estimated biomarker positivity rather than chronological age, which complements traditional longitudinal modeling methods. This terminology should be distinguished from general biological aging clocks. Our clock models are developed using the single biomarker %p-tau217, which reflects pathological processes of both amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles23. Although these pathologies typically evolve jointly during the progression of AD, our approach does not explicitly model their joint evolution. Instead, by leveraging the strong associations of %p-tau217 with both amyloid and tau PET, our models may capture an integrated measure of disease progression.

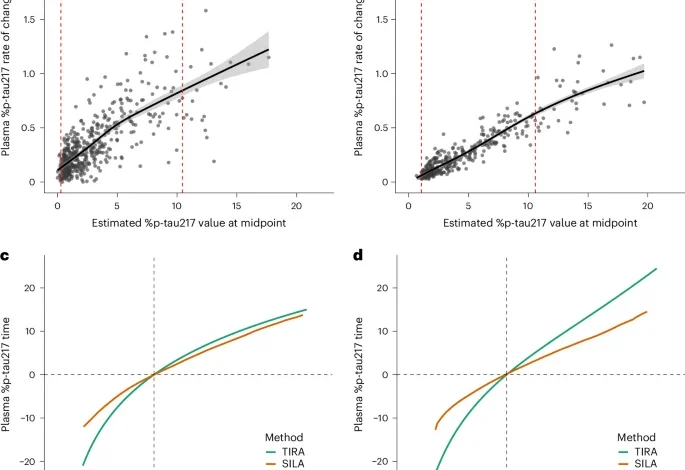

The rate of change in plasma %p-tau217 as a function of the estimated %p-tau217 value at the midpoint was modeled with GAMs as previously described13. To determine the range of plasma %p-tau217 values over which rates of change were consistent, we quantified prediction uncertainty using squared standard errors from GAMs, which represent the variance of model-estimated rates. As was previously described for models using amyloid and tau PET13, intervals with variance in rates of change below the 90th percentile were identified. Plasma %p-tau217 values within the interval of consistent change were used for developing clock models.

The TIRA approach estimates individual plasma %p-tau217 rates of change using linear mixed-effects modeling with random slopes and intercepts10,16. The rates of change are used in GAMs with cubic splines to characterize nonlinear relationships between the rates of change and plasma %p-tau217 levels at the estimated midpoint of follow-up. The inverse of the modeled rate of change is integrated to derive the time between plasma %p-tau217 values.

The SILA algorithm models longitudinal biomarker trajectories through discrete rate sampling and numerical integration17. The method estimates the first-order relationship between biomarker accumulation rate and biomarker levels by sampling rates across evenly distributed values and then applies Euler’s method to numerically integrate this relationship into a non-parametric biomarker versus time curve.

Both clocks were centered so that time zero was a plasma %p-tau217 value of 4.06%, which aligns with an amyloid PET Centiloid value of 20 (ref. 23). To obtain an estimated age of plasma %p-tau217 positivity, participants with at least one %p-tau217 value between 1.06% and 10.45% were included. The plasma %p-tau217 clocks were used to calculate an individual’s estimated age of %p-tau217 positivity by subtracting the %p-tau217 time from the age at the plasma collection. For example, if an 80-year-old person had a plasma %p-tau217 value of 7.06%, which corresponds to 8.8 years from %p-tau217 positivity (based on the Knight ADRC TIRA clock), their estimated age at %p-tau217 positivity would be 71.2 years (80 years minus 8.8 years). For individuals with more than one plasma %p-tau217 value, their estimated age at %p-tau217 positivity was an average of estimates from all plasma samples.

Scatter plots were generated with data points being color coded by cohort for visualization, to assess the concordance of estimated ages of plasma %p-tau217 positivity between different clock models (TIRA and SILA) and across cohorts (Knight ADRC and ADNI). Associations were evaluated using metrics of adjusted R2, Spearmanʼs r and CCC.

Modeling the probability of developing symptomatic AD

The onset of AD symptoms was defined as the first clinical assessment when initially cognitively unimpaired (CDR = 0) individuals with positive AD biomarkers (based on %p-tau217) were found to be cognitively impaired (CDR > 0) with an AD clinical syndrome. For participants who were cognitively normal at baseline, we used interval-censored and right-censored Cox proportional hazards regression models to examine the association between estimated age at plasma %p-tau217 positivity and time to cognitive impairment, accounting for the uncertainty in exact onset timing inherent in longitudinal studies. For participants who remained cognitively unimpaired throughout follow-up, survival times were right-censored at their last assessment age. To account for variable time between assessments, the time of AD symptom onset was interval-censored between the last cognitively unimpaired assessment and the first symptomatic AD assessment. In a sensitivity analysis, participants with cognitive impairment at baseline were included in the models and were left-censored. The models were fitted using the icenReg package in R with semi-parametric baseline hazard estimation. Bootstrap resampling (n = 5,000 samples) was performed to obtain robust standard errors and confidence intervals. Model discrimination was assessed using C-indexes calculated specifically for interval-censored data. Survival curves were generated to visualize the probability of remaining cognitively unimpaired across different estimated plasma %p-tau217 positivity age groups. Survival models treated estimated age at %p-tau217 positivity as a fixed covariate from the clock model estimation.

Estimating the age of AD symptom onset

For individuals with AD symptom onset after plasma %p-tau217 positivity, linear models estimated AD symptom onset as a function of the estimated age of %p-tau217 positivity. Sensitivity analyses included individuals with AD symptom onset prior to plasma %p-tau217 positivity. Sex, years of education and APOE ε4 carrier status were considered as covariates in the models but not included in the final models due to not being significant predictors. Model diagnostics were conducted to ensure the appropriateness of linear modeling. Normality of residuals was assessed using Shapiro−Wilk tests; homoscedasticity was evaluated using Breusch−Pagan tests; and linearity was confirmed through Akaike information criterion (AIC)-based model comparison and F-tests comparing linear, quadratic and cubic polynomial specifications. Sensitivity analyses were performed by refitting models after excluding observations with Cook’s distance > 4/n to assess model robustness to influential points.

Participant data were visualized as raster plots with estimated age at plasma %p-tau217 positivity on the y axis and estimated years from %p-tau217 positivity on the x axis, with participants ordered by their estimated positivity age and color coded by clinical diagnosis category to illustrate the temporal relationship between estimated %p-tau217 positivity and symptom onset. The estimated age at symptom onset from the linear models was overlaid on the plots to aid visualization of how the timing of symptom onset varies as a function of estimated years since plasma %p-tau217 positivity.

Examining predicted AD symptom onset across longitudinal cognitive assessments

To examine cognitive impairment risk across different temporal frameworks, we used Kaplan−Meier curves with different timelines. The primary analysis used time from baseline plasma %p-tau217 collection to onset of cognitive impairment. We also used estimated years from plasma %p-tau217 positivity and estimated years from predicted symptom onset, where predicted symptom onset age was calculated using the linear models described above. Kaplan−Meier curves were combined with density plots showing the distribution of observed events to visualize both survival probabilities and the timing of actual cognitive impairment for each outcome. For each timescale, we binned participants by age at estimated %p-tau217 positivity (

Alignment of biological AD stages and plasma %p-tau217-derived measures

Statistical comparisons were performed to evaluate differences in plasma %p-tau217 levels and estimated years from %p-tau217 positivity across the four 2024 Alzheimer’s Association biological stages: stage A (normal biomarkers; equivalent to A−Tearly−Tlate−), stage B (AD pathologic change; equivalent to A+Tearly−Tlate−), stage C (AD; equivalent to A+Tearly+Tlate−) and stage D (advanced AD; equivalent to A+Tearly+Tlate+). Pairwise comparisons between all groups were conducted using non-parametric Conover−Iman tests with Benjamini−Hochberg adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Development of additional plasma clocks

The same methodology for developing clocks was implemented using Fujirebio Lumipulse p-tau217/Aβ42 and p-tau217, C2N Diagnostics p-tau217, Janssen LucentAD Quanterix p-tau217 and ALZpath Quanterix p-tau217. Thresholds for each were obtained from previously work23. Thresholds were 2.34 pg ml−1 for C2N Diagnostics p-tau217, 0.158 pg ml−1 for Fujirebio Lumipulse p-tau217, 0.0615 pg ml−1 for Janssen LucentAD Quanterix p-tau217 and 0.444 pg ml−1 for ALZpath Quanterix p-tau217.

Software used

R version 4.4.1 was used for all analyses except SILA models, which used MATLAB 2024b. Data manipulation and visualization were performed using the ‘tidyverse’ package for core data handling. Statistical annotations and advanced plot arrangements used the ‘ggpubr’ package. Publication-ready plot themes were achieved using the ‘cowplot’ package. Multiple plots were combined and arranged using the ‘patchwork’ package. Specialized distribution visualization was implemented using the ‘ggdist’ package. Project management utilities included the ‘here’ package for project-relative file path management and the ‘conflicted’ package for function conflict resolution. Parallel computing support was enabled by the ‘doParallel’ package to enhance computational efficiency.

Statistical modeling employed several specialized packages. Linear mixed-effects modeling was conducted using the ‘nlme’ package. Generalized additive modeling was implemented using the ‘mgcv’ package. Interval-censored regression modeling was implemented using the ‘icenReg’ package. CCC analysis was conducted using the ‘DescTools’ package. Survival analysis used the ‘survival’ package with advanced survival plotting provided by the ‘survminer’ package. Statistical tests and post hoc comparisons were performed with the ‘rstatix’ package.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.