Tech alone won’t stop poaching, but it’s changing how rangers work

- New conservation technologies are being developed and deployed worldwide to counter increasingly sophisticated poachers.

- A new alliance between two of the biggest open-source conservation technology platforms combines real-time data collection and long-term data analysis, with proven success.

- Free, open-source tools can help remove barriers to adoption of conservation technology, particularly in the Global South.

See All Key Ideas

As anti-poaching techniques have improved over the years, poachers have increasingly used technology to evade detection by patrols and park rangers. Now, conservationists are rising to the challenge of the resulting technological arms race with innovations of their own.

Over the past few years, researchers and conservationists have worked to develop new technology to detect and track poaching, including mobile apps, sensors, and AI. In an effort to determine which devices, strategies, and technologies are most effective, researchers assessed a suite of new developments that have been deployed or hold promise, in a recent study published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

“There’s all these tools out there to try and push back against something that is increasingly well financed, increasingly organized and difficult to combat,” said study co-author Drew Cronin, a conservation biologist at the North Carolina Zoo.

Leopard sitting in a tree on the Mara North Conservancy in Kenya’s Maasai Mara. Photo Credit: Maria Meinen.

The researchers found that mobile devices and apps are especially cost-effective for documenting poaching and for mapping the location of wildlife. Many useful apps have been developed, including WildScan, which contains a library of photos and descriptions of protected species that can help law enforcement and transport workers identify illegal wildlife trafficking.

Acoustic sensors are already frequently deployed to non-invasively detect and monitor the presence of animals. This technology has gotten better and less expensive in recent years, making it an effective way to monitor vast areas for sounds like gunshots and chainsaws that could indicate poaching or other illegal activity. AI-powered systems, such as wpsWatch, analyze live footage from camera traps and other surveillance systems to detect unusual changes in the environment, including light, sound, and movement, allowing field staff to quickly respond to potential threats including poachers.

Jes Lefcourt, director of EarthRanger. with a Save the Elephants staff member reviewing field data during a visit to Samburu. Photo Credit: Jane Wynyard, Save the Elephants.

As a case study, the team took a closer look at the tech being employed in Kafue National Park in Zambia. Along with the surrounding ecosystem, the park hosts the country’s largest population of cheetahs, more than 200 lions, and 21 species of antelope, all facing intense poaching and habitat loss.

Park managers combined two open-source software platforms to keep track of the different technologies being deployed and to coordinate with local law enforcement and conservation groups. The EarthRanger web application helped them track the movement of vehicles, patrol teams, and radio-collared animals, with a focus on protecting wild cats in real time. They deployed the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART) to aggregate data from the park’s 49 patrol teams, monitor routes, and track sightings.

“It’s the evolution of this whole field,” said Jordan Steward, a communications specialist at EarthRanger. “Leading conservation technologies coming together and saying there’s too much fragmentation in the field, we need to come together to help simplify things.”

Conservationist in Malawi demonstrating how their camera trap records activity at the site and how those records inform their decision-making. Photo Credit: Jordan Steward, EarthRanger.

With the help of the platforms, teams used foot patrols and aerial surveillance to cover over 210,000 kilometers (130,000 miles) and make 322 apprehensions in 2021. “They saw, across the board, declines in threats in the Greater Kafue Ecosystem, and then stable or increasing carnivore populations, which is their goal,” said Cronin, who is on the leadership team for the SMART Partnership.

The two platforms have been used in thousands of conserved and protected areas in over 100 countries since their introductions around a decade ago, but only recently formed a formal partnership with the goal of combating increases in poaching and other illegal activities, as well as expanding access to the technology. They organized a joint conference on conservation technology on November 3 in Hanoi, Vietnam, attended by conservationists and scientists from around the world.

“I think the really fantastic thing about almost all of the tools highlighted in this paper, but especially SMART and EarthRanger and the Conservation X tools, is that they were very intentionally developed with frontline practitioner and user input from the beginning,” said conservation scientist Meredith Palmer of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, who was not involved in the new study. “Which is something that greatly enhances the usefulness and accessibility of these tools.”

Improvements to conservation technology are only a part of the larger conservation puzzle, Cronin said. Funding, training, and ease of adoption of the technology remain a barrier to many conservationists, particularly in the Global South.

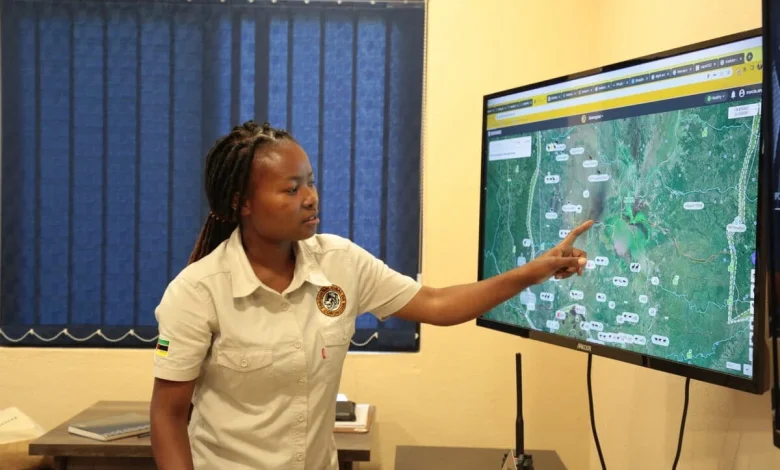

Gorongosa National Park team member presenting how they visualize wildlife, personnel, and other activity across the landscape on EarthRanger. Photo Credit: Gorongosa National Park.

Even with cutting-edge conservation technology available for the first time, Cronin said, people, not computers, remain at the helm of protecting at-risk ecosystems, with volunteers, foot patrols, and park managers on the front lines.

“It’s less about pushing the newest and greatest AI algorithm onto some practitioner in Zambia, and more about thinking about what they need and providing them with a solution that’s going to work,” he said. “It has to be free, and it has to be open and accessible.”

Daniella Garcia Almeida is a graduate student in the Science Communication M.S. Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Other Mongabay stories produced by UCSC students can be found here.

Citation:

Lynam, A. J., Cronin, D. T., Wich, S. A., Steward, J., Howe, A., Kolla, N., … & Cox, H. (2025). The rising tide of conservation technology: empowering the fight against poaching and unsustainable wildlife harvest. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 13, 1527976. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2025.1527976