Drifting towards deflation in the Euro zone

In yesterday’s preview of 2026, one of my four predictions was that the Euro zone will resume its drift back towards deflation. The main reason for this is that the currency union is stuck in the same kind of paralysis that has reigned since the sovereign debt crisis in 2011/12. That crisis was papered over by the ECB, which has morphed into a fiscal bailout vehicle for high-debt countries, while nothing was ever actually done to bring down debt overhangs in Italy and Spain. As a result, neither country has fiscal space, which means every shock descends into wrangling over joint EU debt issuance. That’s an inherently deflationary equilibrium. Speed and magnitude of policy stimulus will always be too small. This dysfunction compounds into chronic underperformance and deflation over time.

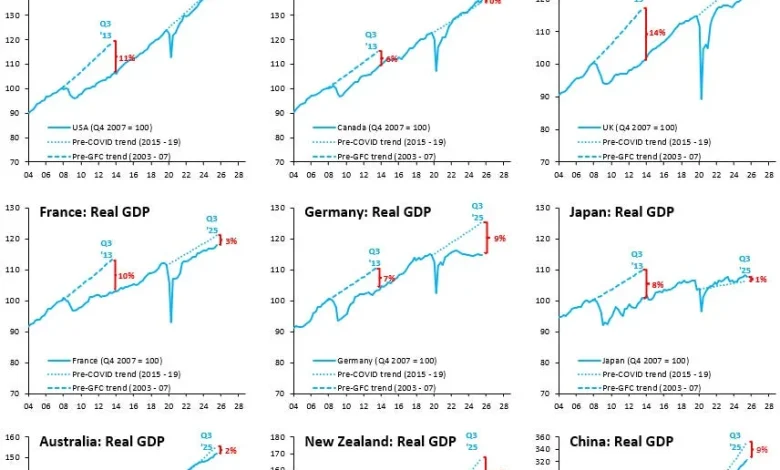

There’s one big difference from the sovereign debt crisis in 2011/12 however. At the time, Germany was chalking up solid growth rates, while it’s really struggling at the moment. This means that deflationary pressure is radiating out from Germany now, while the opposite was true after the sovereign debt crisis. In today’s post, I take a look at economic slack across the world’s major economies. Germany is the only country where economic slack is now bigger than after 2008.

Before I get into the weeds, an important caveat: no one has any clue how to estimate economic slack. People often calculate output gaps as the difference between GDP and “potential,” which is usually some kind of time-series moving average. The issue is that time-series averages follow actual GDP much too closely, so when a country goes into a prolonged downturn, output gap estimates are small because potential GDP follows actual GDP down. To avoid this issue, I calculate a linear trend for GDP based on the average quarterly growth rate in the five years before COVID and do the same thing for the five years before the 2008 crisis. Of course, my linear trends can hardly be thought of as potential either. But they’re a better approximation of slack – in my view – than some kind of moving average.

As the panel of charts above shows, Germany’s GDP as of Q3 ‘25 was nine percent below its pre-COVID trend, a bigger gap than after the global financial crisis on a comparable time scale. In Q3 ‘13, this gap was seven percent. Germany is the only place where the gap is currently bigger than it was then. Deflationary pressure will be radiating out from Germany to the rest of the Euro zone.

It’s also worth noting that essentially no country has GDP currently above its pre-COVID trend, while many countries have GDP substantially below, including China, France and the UK. The global equilibrium we’re slipping into is a deflationary one, much like in the decade after the global financial crisis.