AI-enabled virtual spatial proteomics from histopathology for interpretable biomarker discovery in lung cancer

Study design

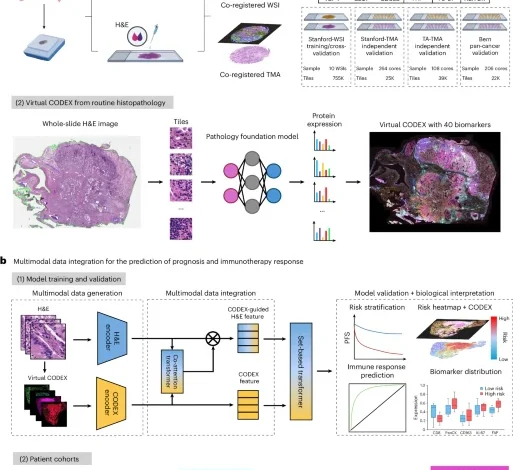

This study included a total of 2,308 patients across seven independent cohorts of patients with NSCLC. Three cohorts—Stanford-WSI, Stanford-TMA and TA-TMA—contained same-section co-registered H&E and 40-plex CODEX images and were used for training and validation of the HEX model for AI-enabled generation of spatial proteomics. To evaluate HEX’s generalizability and robustness across different tissue types and histological protocols, we conducted external validation using a pan-cancer dataset comprising matched 57-plex CODEX and H&E images from 34 tissue types. To assess the clinical relevance of HEX-derived features, we analyzed H&E-stained slides from six cohorts—NLST, TCGA, PLCO, Stanford-TMA, TA-TMA and Stanford immuno-oncology (Stanford-IO)—through multimodal integration for outcome prediction. Across these cohorts, 2,150 patients had available data on RFS, DSS or overall survival and 148 patients treated with ICIs had objective response and PFS outcomes. To assess the clinical utility beyond NSCLC, we further evaluated HEX for prognosis prediction across 12 additional cancer types in TCGA (n = 5,019). This retrospective study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. An overview of the study cohorts and experimental design is provided in Fig. 1 and detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Extended Data Fig. 2. Comprehensive descriptions of each patient cohort and associated tumor samples are provided in the sections below.

CODEX with high-plex PhenoCycler imaging

Tissue preparation

Human lung formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks and TMAs were sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm and mounted directly onto SuperFrost Plus microscope slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Slides were stored at 4 °C.

Marker panel design

We selected 40 protein markers based on their known biological roles and clinical relevance in NSCLC and the tumor microenvironment. These markers include lineage-specific, structural, functional, immune checkpoint, stromal, vascular, extracellular matrix remodeling and antigen presentation proteins. The 40-plex panel was optimized to capture a broad spectrum of tumor–immune phenotypes and spatial interactions at single-cell resolution.

Antibodies

Antibody conjugation was performed by the Stanford Cell Sciences Imaging Facility using carrier-free antibodies. Briefly, antibodies were buffer exchanged and reduced using centrifugation filters and a reduction master mix. Barcodes were resuspended and incubated with the reduced antibodies for 2 h at room temperature, followed by purification and storage in antibody stabilization buffer at 4 °C. Commercial antibodies were primarily sourced from Akoya Biosciences and other vendors (Supplementary Table 1). For antibodies not commercially available, custom conjugations were performed using pre-validated primary antibodies and designed barcodes, following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. All antibodies underwent validation for specificity and performance using PhenoCycler multiplexed imaging.

High-plex staining and imaging

Tissue staining and imaging were performed following the PhenoCycler-Fusion User Guide version 2.1.0. Briefly, after overnight baking at 60 °C, slides were deparaffinized using a standard histological procedure. Antigen retrieval was conducted in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) in a pressure cooker at 120 °C for 20 min under high pressure. After cooling to room temperature, slides were rinsed twice in double-distilled water and incubated in a photobleaching buffer for 45 min. After extensive washing in 1× phosphate-buffered saline, slides were hydrated and stained, per the manufacturer’s protocol. Slides were incubated in the conjugated antibody cocktail overnight at 4 °C in a humidity chamber, followed by post-staining fixation and washing steps, as instructed in the manufacturer’s user manual.

High-plex immunofluorescence imaging was performed using the PhenoCycler 2.0 platform with a 20× objective. Images were acquired in DAPI, AF488, Atto550 and AF647 channels and automatically processed into a qpTIFF file.

H&E staining of the same section after CODEX

Following PhenoCycler imaging, slides were stored at 4 °C in the storage buffer provided with the PhenoCycler-Fusion Stain Kit. Flow cells were removed from the slides according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After extensive washing with 1× PhenoCycler buffer, slides were stained with standard H&E protocols and imaged on a Leica Aperio AT2 scanner at 40× magnification.

CODEX and H&E image registration and dataset construction

The DAPI images in CODEX were registered to the hematoxylin channel of the H&E images using PALOM (version 2024.4; https://github.com/labsyspharm/palom), with key parameters including full-resolution alignment (level=0), affine initialization using 4,000 keypoints at pyramid level 1, and block-wise shift refinement. Registered images were divided into non-overlapping tiles with a size of 224 × 224 pixels, and the average expression of each of the 40 protein biomarkers in CODEX was computed for the corresponding H&E image tile. We analyzed three cohorts with matched H&E and 40-plex CODEX staining: (1) Stanford-WSI, comprising ten WSIs from Stanford Hospital, yielded 754,836 tiles annotated with 40-marker expression profiles and was used for model training and cross-validation, with patients split 80/20 into training and test sets in each fold; (2) Stanford-TMA, including 264 TMA cores, contributed 25,383 tiles; and (3) TA-TMA, comprising 108 TMA cores from TissueArray, contributed 39,313 tiles. Stanford-TMA and TA-TMA datasets were used exclusively for independent validation of H&E-based protein expression.

To evaluate the spatial accuracy of CODEX–H&E co-registration, we performed independent cell segmentation on each modality using modality-specific pipelines for Stanford-WSI. The transformation computed by PALOM was then applied to map CODEX cell centroids into the H&E coordinate frame. For each cell in the H&E image, we computed the Euclidean distance to the nearest mapped CODEX cell. We also measured the diameter of each cell nucleus as a biological reference scale. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 30, 99.2% of cell–cell distances between H&E and CODEX were smaller than the median cell nucleus diameter, indicating that accurate cross-modality alignment is achieved with a subcellular resolution.

Pan-cancer CODEX–H&E dataset for protein prediction

For external validation, we used a pan-cancer dataset comprising 206 TMA cores spanning 34 distinct tissue types, including malignant, benign and normal tissues. The tissue types include: adrenal gland, biliary system, bone, bone marrow, brain, breast, cervix, colon, kidney, liver, lung, lymph node, meninges, muscle, musculoskeletal tissue, nasopharyngeal tissue, nerve, ovary, pancreas, parathyroid, placenta, pleura, prostate, salivary gland, skin, soft tissue, spleen, stomach, tendon, testis, thymus, thyroid, tonsil and uterus11. Samples were obtained from the University of Bern, prepared using a distinct H&E staining protocol and digitized at 20× magnification using a Keyence BZ-X710 scanner. CODEX imaging was performed with a 57-marker panel, including 33 protein markers not present in the original NSCLC panel, allowing evaluation of HEX’s ability to generalize to novel targets and diverse tissue types.

Patient cohorts for clinical outcome prediction

Cohorts for prognosis prediction

We assembled five NSCLC cohorts totaling 2,150 patients with H&E-stained images and associated clinical outcomes to evaluate the prognostic utility of HEX-generated virtual spatial proteomics. The NLST28, a large multicenter randomized trial conducted in the USA, served as the training set and included participants with NSCLC and available RFS data. Four independent validation cohorts were used: (1) the TCGA cohort, comprising patients with lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma whose WSIs and RFS data were downloaded from the Genomic Data Commons; (2) the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial cohort29, with deidentified WSIs and DSS data obtained via the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Data Access System; (3) the Stanford-TMA cohort; and (4) the TA-TMA cohort, with Stanford-TMA and TA-TMA both comprising NSCLC cases along with curated WSIs and annotated RFS and overall survival outcomes, respectively. All cohorts were restricted to histologically confirmed NSCLC and included clinical metadata such as stage, survival endpoints and demographic variables (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Cohort for immunotherapy response prediction

We assessed the clinical utility of HEX-generated virtual spatial proteomics for predicting immunotherapy response and outcomes in the Stanford-IO cohort. The cohort included 148 patients with advanced (metastatic or recurrent) NSCLC who received anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 ICIs at Stanford. The inclusion criteria were treatment with ICIs with or without concurrent chemotherapy and H&E-stained slides available from a pretreatment core needle or surgical biopsy. The best overall response was categorized as responder (complete or partial response) or non-responder (stable or progressive disease). PFS was defined as the time from treatment initiation to clinical or radiographic progression or death. Patients without progression were censored at the date of last follow-up. Detailed clinicopathological characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table 4.

WSI processing

All H&E images were processed at 40× magnification (~0.25μm px−1). Slides scanned at lower resolutions were rescaled to 40× to ensure consistency across datasets. This resolution is compatible with the MUSK backbone, which was pretrained using multi-scale image augmentations including 10×, 20× and 40× fields of view22. To minimize the influence of image artifacts, regions containing pen marks, tissue folds or blurring were identified and excluded using color-based filtering techniques60. Before feature extraction, all H&E tiles were standardized using pixel-wise normalization (mean = 0.5; s.d. = 0.5), matching the MUSK training distribution. For CODEX data, each biomarker channel was normalized by scaling the intensities to the [0, 1] range based on the 99th percentile of its global intensity distribution. For each processed H&E image, the HEX model was applied to generate a corresponding virtual spatial proteomics profile, which was subsequently used for multimodal data integration. For orthogonal validation using IHC, we co-registered adjacent-section IHC and H&E WSIs, resampled all slides to 0.25 μm px−1 resolution and extracted protein signals from the 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) channel via hematoxylin–eosin–DAB (HED) color deconvolution.

HEX model architecture and training strategy

The HEX model was designed to predict the expression level for 40 protein biomarkers simultaneously, given an input H&E image patch (typically 224 × 224 pixels in this study). An overview of the model architecture is visualized in Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1. The backbone of HEX is built on a pretrained pathology foundation model, such as MUSK, to extract visual features from H&E patches. A two-stage regression head follows: a linear layer reducing the visual embedding to 256, followed by ReLU and dropout, then another linear layer projecting to 128 dimensions with ReLU and dropout and finally a linear output layer producing 40 biomarker predictions.

To improve the predictive robustness and handle the inherent challenges in multiplex imaging data, we integrated two key techniques during fine-tuning: FDS61 and an ALF62. Spatial proteomics data such as CODEX exhibit substantial target imbalance: some biomarkers are ubiquitously expressed, whereas others appear infrequently or in sparse regions. To mitigate this, we adopted FDS, a post-hoc feature calibration technique that reduces the negative impact of data imbalance by explicitly smoothing features across similar target values. During training, features from the penultimate layer are first collected and stored for each target bin of biomarker j and then updated via the exponential moving average63. The calibrated features \(\bar{h}\) are obtained by smoothing these bin-level features using a Gaussian kernel \(g\left(\bullet \right)\):

$$\bar{h}={\bar{C}}_{b}^{\frac{1}{2}}{C}_{b}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\left(h-{\mu }_{b}\right)+{\bar{\mu }}_{b}$$

where

$${\mu }_{b}=\frac{1}{{N}_{b}-1}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i\in b}{h}_{i},{C}_{b}=\frac{1}{{N}_{b}-1}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i\in b}\left({h}_{i}-{\mu }_{b}\right){\left({h}_{i}-{\mu }_{b}\right)}^{T}$$

$${\bar{\mu }}_{b}=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{m\in B}g\left({y}_{b},{y}_{m}\right){\mu }_{m},{\bar{C}}_{b}=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{m\in B}g\left({y}_{b},{y}_{m}\right){C}_{m}$$

\({\mu }_{b}\) and \({C}_{b}\) are the mean and covariance of the features with each bin \(b\in B\), and \({N}_{b}\) is the total number of samples in the bth bin. FDS was applied directly across all biomarkers to jointly regularize and smooth the feature distributions. This explicit calibration in feature space reduces bias in under-represented targets and stabilizes training in imbalanced regression settings.

To further mitigate the impact of image noise and outliers commonly observed in CODEX data, we incorporated the ALF into the training objective. The ALF generalizes robust loss functions by introducing the learnable shape \(\alpha\) and scale \(c\) parameters that modulate the tail behavior of the error distribution. This design allows the model to dynamically interpolate between different loss regimens based on data characteristics. When interpreted as the negative log-likelihood of a univariate probability distribution, ALF enables robustness to be automatically adapted during training, improving generalization to noisy or heterogeneous regions in histopathology. The ALF in this study is defined as

$${\mathcal{L}}\left(r,\alpha ,c\right)=\rho \left(r,\alpha ,c\right)+\log Z\left(\alpha \right)$$

where

$$\rho \left(r,\alpha ,c\right)=\frac{|\alpha -2|}{\alpha }\left({\left(\frac{{\left(r/c\right)}^{2}}{\alpha -2}+1\right)}^{\alpha /2}-1\right)$$

and \(Z\left(\alpha \right)\) is the partition function, \(\alpha\) is the shape parameter, \(c\) is the scale parameter and \(r\) is the residual error.

HEX model training details

The network backbone for HEX was pretrained using unified masked modeling (MUSK) on 50 million pathology images from 11,577 patients and one billion pathology-related text tokens. HEX was then trained on matched H&E and spatial proteomic profiles using the Adam optimizer to minimize the ALF, with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−5, exponential decay (factor = 0.95), a batch size of 384 and a dropout rate of 0.5. Training was conducted over 120 epochs: during the first 100 epochs, only the last four encoder layers and regression heads were trained, with the remainder of the backbone frozen; in the final 20 epochs, the regression heads were updated while the entire backbone remained frozen. Training-time data augmentation included random horizontal and vertical flips, rotations, and jittering in brightness, contrast, saturation and hue. The ALF shape (\(\alpha\)) and scale (\(c\)) parameters were both initialized to 1. For FDS, the start update parameter and start smooth parameter were set to 0 and 10, respectively.

During inference, HEX scans across the entire tissue using a sliding window with a 224-pixel stride, sequentially generating predictions for each tile and stitching them together into a seamless, fully reconstructed virtual CODEX map. On standard hardware (8× NVIDIA L40S GPUs; batch size: 16), this process takes ~1.3 min per WSI at 40× magnification. HEX also supports single-GPU inference with ≥8 GB of video random access memory. Although these patch and stride sizes served as the default throughout our analyses, the HEX framework supports smaller step sizes, allowing users to generate virtual proteomics maps at higher spatial resolutions as needed. To generate high-resolution virtual CODEX outputs for enhanced visualization of fine-grained biomarker distributions, HEX was retrained on a 1/20 subset of the training dataset using the same input patch size (224 × 224), but with a smaller prediction window (14 × 14 pixels) and a step size of 14 pixels. In this configuration, the model predicts the average expression over the central 14 × 14 region of each input patch, enabling finer spatial resolution in the reconstructed virtual proteomic maps.

HEX model evaluation and comparison

For a comprehensive evaluation of predictive accuracy, we computed four complementary metrics: Pearson’s r, which captures the strength of linear relationships between predicted and true expression values; Spearman’s r, which measures rank-order consistency and reflects the model’s ability to preserve relative expression trends; SSIM64, which quantifies perceptual similarity between spatial maps by considering luminance, contrast and structural patterns; and MSE, which penalizes large deviations in absolute expression levels.

For comparison, we benchmarked HEX against two state-of-the-art generative models for stain translation: a conditional GAN-based method (DeepLIIF)20 and a contrastive unpaired translation model (Virtual Multiplexer, based on CUT)18. These frameworks were selected due to their relevance to histology-to-immunostaining translation tasks. We used their publicly available implementations, adhered to the original training protocols and retrained both models from scratch on our paired H&E–CODEX dataset to predict all 40 biomarkers, ensuring a fair and consistent evaluation. Additionally, we conducted ablation studies demonstrating that both FDS and ALF are critical components for achieving robust and generalizable performance in HEX.

Model architecture for integrating histology and virtual spatial proteomics

We developed a deep learning framework that integrates H&E histology and virtual spatial proteomics for predicting patient prognosis and immunotherapy response. The MICA model learns how histological features attend to protein expression patterns to make clinically relevant predictions.

MICA begins by extracting tile-level features from H&E images using a pretrained pathology foundation model (MUSK), producing a histology feature bag \({H}_{{bag}}=\left\{{h}^{i}\right\}\in {R}^{I\times {d}_{k}}\), where \(I\) is the number of tiles per patient and \({d}_{k}\) is the feature dimension. Simultaneously, protein expression features are obtained from each CODEX channel using DINOv2 (ref. 65)—pretrained on 142 million natural images—resulting in a CODEX feature bag \({M}_{{b}{a}{g}}=\left\{{m}^{j}\right\}\in {R}^{J\times {d}_{k}}\), where \(J\) is the number of protein channels.

To fuse these two modalities, we introduce a CODEX-guided co-attention mechanism. This early fusion approach allows the model to selectively focus on histological regions most relevant to the spatial proteomic signals. In the CODEX-guided co-attention layer, we project \({M}_{\mathrm{bag}}\), \({H}_{\mathrm{bag}}\) and \({H}_{{b}{a}{g}}\) into query \(Q\), key \(K\) and value \(V\) representations via three learnable transformations—\({P}_{q}\), \({P}_{k}\) and \({P}_{v}\in {R}^{{d}_{k}\times {d}_{k}}\):

$$Q={M}_{\text{bag}}{P}_{q},\,\,K={H}_{\text{bag}}{P}_{k},\,\,V={H}_{\text{bag}}{P}_{v}$$

The CODEX-guided H&E representation is computed as

$${\widetilde{H}}_{\mathrm{coa}}=\mathrm{softmax}\left(\frac{Q{K}^{T}}{\sqrt{{d}_{k}}}\right)V$$

This operation enables CODEX-derived features to guide attention over H&E image tiles, highlighting regions of interest and capturing complex multimodal spatial interactions. Finally, two modality-specific multiple-instance learning transformers66 with global average pooling aggregate features for outcome prediction. Unlike conventional late-fusion approaches, this strategy enables richer cross-modal representation learning and enhances both interpretability and predictive performance.

Training and evaluation of MICA

For each H&E image, tissue segmentation was performed using the publicly available CLAM repository67. Following segmentation, non-overlapping tiles of size 384 × 384 pixels were extracted at 20× magnification from all identified tissue regions. The pretrained MUSK model was then used as a feature extractor to generate histology feature bags. For CODEX, features from each protein channel were extracted using DINOv2 (dinov2_vits14_reg), yielding corresponding CODEX feature bags. Due to variable bag sizes, we employed a mini-batch size of 1, sampling paired H&E and virtual CODEX inputs. No data augmentation was applied for either modality.

For prognosis prediction, MICA was trained using a discrete-time survival loss68 with the Adam optimizer (learning rate: 1 × 10−5; weight decay: 1 × 10−5), a batch size of 1 and eight gradient accumulation steps. The model weights of both MUSK and DINOv2 were frozen. No early stopping was applied, and all models were trained for 20 epochs with all parameters trainable.

We evaluated MICA’s prognostic performance in three settings: (1) independent NSCLC validation, whereby MICA was trained on the full NLST cohort (RFS) and evaluated on four external NSCLC cohorts (TCGA (RFS), Stanford-TMA (RFS), PLCO (DSS) and TA-TMA (overall survival)); (2) within-cohort robustness, whereby fivefold cross-validation was conducted within the three largest cohorts (NLST, TCGA and PLCO); and (3) pan-cancer generalization, whereby fivefold cross-validation (DSS) across 12 additional TCGA tumor types (5,019 patients) was performed to assess robustness and generalizability.

For immunotherapy response prediction, MICA was trained using either cross-entropy loss (for objective response) or discrete survival loss (for PFS), using the Adam optimizer (learning rate: 2 × 10−4; weight decay: 1 × 10−5), with a batch size of 1 and eight gradient accumulation steps. Training was performed for 20 epochs, and all models were evaluated using fivefold cross-validation.

For comparative evaluation, we used attention-based multiple-instance learning (AbMIL)69 as the unimodal baseline for both H&E-only and virtual CODEX-only models. The H&E-only baseline was implemented using image features extracted from the MUSK foundation model, corresponding to the MUSK image approach described in our previous work. The virtual CODEX-only model used DINOv2-extracted features from virtual proteomic images. Additionally, we benchmarked MICA against PORPOISE30, a deep learning method for late fusion of multimodal data. All models were trained under the same settings as MICA. Performance was evaluated using the C-index, whereas Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to assess the risk stratification capability of each method.

Biological interpretation of outcome predictions

To explore the biological relevance of the model predictions, we used integrated gradients31—a gradient-based attribution method that quantifies the contribution of input features to the model’s output. In our context, positive attributions indicate features associated with increased predicted risk, whereas negative attributions correspond to decreased risk. The integrated gradient was computed using the IntegratedGradients function from the Captum library (version 0.4.0), with a zero vector used as the baseline. After calculating integrated gradient values for each H&E tile, we applied min–max normalization across the WSI to facilitate comparison.

We aggregated integrated gradient scores across the entire dataset and defined high- and low-risk groups as the top and bottom 1% of tiles by integrated gradient value, respectively. For each tile, we computed the average expression of each biomarker in the corresponding CODEX image, enabling comparison of protein expression profiles between risk groups.

We further defined a tile as expressing a high level of a biomarker if its value exceeded the 80th percentile of that marker’s distribution across the dataset. Based on this, we assessed the fraction of tiles showing co-expression of biomarker pairs. To characterize SCSs, we counted the number of tiles containing both marker-defined cell states in a given pair and computed a normalized Jaccard index to quantify co-localization patterns in the high- and low-risk groups. Specifically, each of the six pre-specified combinations paired a canonical lineage marker with a functional marker to assess distinct cell states relevant to immunotherapy response (granzyme B+/CD8+, TCF-1+/CD4+, PD-1+/CD8+, CD66b+/MMP9+, FAP+/collagen IV+ and CD163+/MMP9+). Given this limited set of biologically informed hypotheses (n = 6), nominal P values were reported without correction for multiple hypothesis testing.

Statistical analysis

For fivefold cross-validation of protein expression prediction, we reported the mean and standard deviation across all folds. For independent validation, we used non-parametric bootstrapping (1,000 replicates) to estimate 95% CIs for all performance metrics. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to evaluate the association between MICA-predicted risk scores and patient survival across cohorts. Patients were stratified into high- and low-risk groups based on either the median or an optimized cutoff value (as specified in the figure captions), and survival differences were assessed using the log-rank test. P

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.