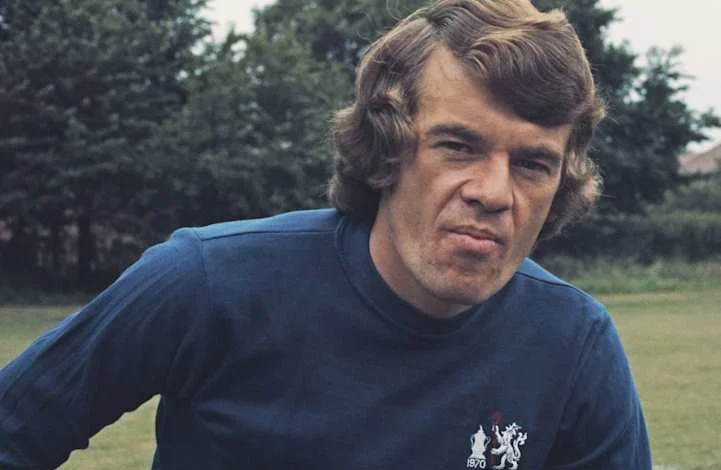

Eddie McCreadie – 1940-2026 | News | Official Site

Chelsea Football Club is today mourning the loss of one of the great figures in our history, a tough but innovative full-back, the scorer of a supreme cup final goal, and – for a fleeting but memorable spell – a touchline leader.

Eddie McCreadie, who passed away yesterday at the age of 85, was one of the small but illustrious group who both played for and managed Chelsea, and he enjoyed notable success in each of those roles.

The Glaswegian first became a Blue in April 1962, signed as a little-known left-back from the Scottish Second Division when we paid East Stirlingshire £5,000 – a transfer fee that would come to be regarded as one of the best bargains in our history. It was the dawn of Tommy Docherty’s colourful time in charge and McCreadie was his first signing. He had been lured north of the border to scout a different player but the 22-year-old quickly caught his eye.

McCreadie made his debut at the very beginning of a season that ultimately ended in promotion. Straightaway the recent arrival was hugely important to how a young and exciting team functioned.

The inexperienced, athletic Scot was expecting a couple of years developing in the reserves. Instead, Docherty paired him with fellow full-back Ken Shellito on the opposite flank, creating an attacking, overlapping force down the flanks, inspired by overseas teams and fresh to the English game.

Both Docherty and his influential coach Dave Sexton were very open to tactical innovation.

In the top division in his second season south of the border, McCreadie continued as the automatic choice at left-back, a steady situation that would continue more or less unbroken into the next decade, even though Shellito was far less fortunate with injuries.

McCreadie’s aggressive, rampaging approach made him a crowd favourite as the vibrant, youthful Blues finished fifth in their first year back in the big time and he scored his first goal, in a home win against West Brom.

A much more famous strike would come the following season, and contributed considerably to Chelsea winning the first major knockout trophy in our history. In a two-leg League Cup final against Leicester City, centre-forward Barry Bridges was absent for the first leg at Stamford Bridge and after much pestering that he had played the position in Scotland, it was to the speedy McCreadie that Docherty threw the no.9 shirt.

The manager’s redeployed compatriot did not disappoint on a muddy pitch, scoring the winner in a 3-2 victory which ultimately proved to be the decisive goal in the tie, yet his attack began from where he would far more usually be playing.

‘I ran from just outside our box,’ McCreadie recalled. ‘It was pretty heavy going. I saw their two centre-backs coming at me and I knew they were going to give me some! I was pretty quick and I just hit the ball between the both of them and I just went.

‘Before I knew it, I had covered a lot of ground and I could see Gordon Banks coming out of the goal towards me and I dived, I got my toe on the ball and it dribbled over the line. If he had stayed on his line, he could have thrown his hat on it. It was exciting, I never scored many goals – five in my Chelsea career.’

Sadly there is no video footage of that historic moment for those not present to enjoy.

McCreadie was back in defence for a resolute display in the away leg and a 0-0 draw secured the silverware. In the FA Cup, he and his colleagues went out at the semi-final stage and they finished third in the league, although it was an end to a season muddied by the infamous ‘Blackpool incident’. McCreadie was one of the eight players sent home by Docherty for breaking a curfew.

Unlike others involved, the defender remained at Chelsea beyond the Docherty era and provided steel and dash to Sexton’s Blues, a side renowned for being able to dish it out as well as turn it on.

Without ever quite acquiring the reputation of ‘Chopper’ Harris alongside him, McCreadie could be tough in the tackle and was great in the air. Nicknamed Clarence by team-mates (after a visually challenged lion in popular TV programme of the time, Daktari). Eddie, the joke went, was never quite certain what he was kicking on the pitch. That aside, his sliding interventions, often rescuing situations to help out fellow defenders, were a trademark.

Although on one occasion his tough-tackling on 48-year-old legend Stanley Matthews did not go down too well with the Chelsea support during his early time at the club, it was always reassuring we could line him up against the likes of George Best in an era of high-quality wingers.

McCreadie’s flying drop-kick on the head of Leeds captain and Scotland team-mate Billy Bremner is woven brightly into the legend of the 1970 FA Cup replay victory at Old Trafford. This from a man with a contrasting side to his character. He read philosophy and wrote poetry in his leisure time.

‘It was part of my escape from football and it was part of trying to find out who the hell I was,’ he explained.

That triumphant FA Cup campaign, in which he played every round, was a career high point, especially for a player who had suffered semi-final defeat two years running before losing in the 1967 final.

The next four seasons were injury-hit and he missed out on the European Cup Winners’ Cup victory over Real Madrid in 1971.

Never the same after one particularly bad Achilles injury, a move into the coaching staff beckoned, first with the reserves and then the first team. The 1973/74 season was the last one in which he played, ending with 410 appearances to his name, all but five of them as a starter. He was the fifth Chelsea player to pass the 400-game mark and represented Scotland 23 times between 1965 and 1969, at the time the most caps earned by anyone while a Chelsea player.

Coaching brought out his personal charisma and before long McCreadie was Chelsea manager, taking over in April 1975 from Ron Suart whose tenure following on from Sexton was short-lived. By this stage the team was relegation-bound and the club was financially destitute. With buying players out of the question, there was a logic to handing the reins to a coach already used to inspiring the young homegrown prospects available.

Immediately he dropped four experienced former team-mates – one of the toughest moments of his career – and replaced them with teenagers. Most tellingly for that game at Tottenham, the new boss handed the captain’s armband on a permanent basis to 18-year-old Ray Wilkins. A new era had begun.

The first full season was a mid-table one in Division Two but just two defeats in the final 12 fixtures was a portent for better things to come.

By the 1976/77 season McCreadie’s youthful Blues, with the odd old hand steadying the journey, were flying in front of healthy-sized crowds, and the timing was vital. Huge debts had been revealed with a one-year moratorium agreed with creditors, plus the forced sale of our training ground. Promotion for survival felt imperative.

It was against this messy backdrop that the then 36-year-old manager not only bonded his young charges together as a force, he persuaded them to take pay cuts.

We went through the whole league season unbeaten at home and the image of McCreadie, clad in a sheepskin coat and wearing 1970s-style sunglasses while appealing for exuberant, celebrating fans to leave the pitch during the promotion run-in, is an iconic Chelsea image of the age.

With Wilkins the jewel, midfielder Garry Stanley pulling strings, and young attackers Steve Finnieston, Kenny Swain and Ian Britton proving prolific, for fans of that era it remains one of their favourite seasons. There was optimism about the return to the top flight, but then came a massive punch to the stomach. McCreadie became embroiled in a summer dispute with the board of directors.

He had been working without a contract and believed he now deserved one. The board claimed they were not in position to grant such terms and their salary offer was not even up for discussion, so they accepted his principled resignation. A players’ deputation to have McCreadie reinstated, led by Peter Bonetti, one of the remaining veterans, failed to repair the damage.

For years after, the successions of short-lived managers who followed him unsuccessfully had to endure the chant of ‘Bring back, oh bring back, oh bring back Eddie McCreadie’ from the terraces. It did not happen.

Crestfallen, McCreadie moved to America where he briefly played, as well as managed, and made Tennessee his permanent home, embracing Christianity there. Forty years after his departure, McCreadie was persuaded to return to Chelsea by a group of supporters for a book launch and special evening at the Bridge, despite a severe aversion to air travel. The visit also incorporated a visit to Cobham to meet the Blues squad of the day.

Delighted to be back one more time after so long away, he made it clear to all that despite the deep pain over the way his time at Chelsea concluded, his love for the club that dominated his career was undiminished.

All at Chelsea Football Club send our deepest condolences to Eddie’s wife Linda and his other family and his friends.