A Wonkish Note on Tariffs and Inflation

This post is an experiment. My original plan on Substack was to use it to post wonky, economistic stuff. But the ‘stack has attracted a broad audience — I currently have 522,288 subscribers (but who’s counting?) — and I don’t want to clutter normal people’s inboxes with ultra-wonky stuff.

So what I’m going to try is putting up occasional wonky posts but not emailing them out, hoping that people who want this kind of thing see them but that they don’t repel the larger audience — basically treating these posts as a blog but not a newsletter. We’ll see how it works.

Today’s topic is the impact of tariffs on inflation. Many news reports treat the absence of a large rise in inflation since Liberation Day as a puzzle, a big problem for economists. And of course Trump and co. are crowing that all the experts were wrong.

But if you look at the actual numbers, there isn’t much if any puzzle.

The key point is that effective tariff rates have risen much less than headline rates. Partly this is because there have been some major carve-outs, like Apple’s exemption from tariffs on India. Partly it’s because high tariffs have led firms to take advantage of exemptions that were already on the books but weren’t worth the paperwork when tariffs were lower. Here, from the Penn-Wharton budget model, are the shares of imports from Canada and Mexico claiming exemption from tariffs under the USMCA:

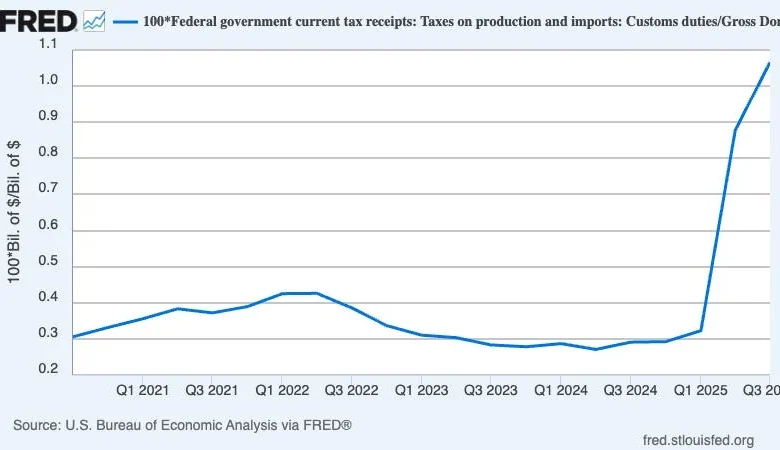

So how much extra inflation should we have expected from the actual, as opposed to headline, rise in average tariff rates? The chart at the top of this post shows a quick and dirty way of getting that number. It shows total customs duties as a percentage of GDP, i.e., the tax actually imposed by the Trump tariff hikes. These receipts rose from 0.3 percent of GDP pre-Trump to 1.1 percent, a rise of about 0.8 percentage points. And that can serve as a first-pass estimate of how much the tariffs should have added to inflation.

OK, that could be an underestimate, because the tariffs have discouraged imports, which means that their impact on prices should have been larger than their impact on revenue. But the revenue still serves, as I said, as a first-pass estimate of how much inflationary impact we’d expect — around 0.8 percent, or a bit more.

So what has actually happened to inflation? Let me go at that two ways.

First, the HBS Pricing Lab, run by some of the same people who created the Billion Prices Index, has been estimating the impact of tariffs on retail prices. Their estimates bounce around, but they suggest that the CPI is 0.8 percentage points higher than it would have been without the tariffs:

Second, compare 2025 inflation with forecasts made before Trump went on his tariff spree. In late 2024 forecasters surveyed by the Philadelphia Fed expected 2.2 percent core PCE inflation — the Fed’s preferred measure — in 2025. We don’t have December 2025 numbers yet, but the Employ America nowcast says 3 percent for annual inflation in 2025, 0.8 percentage points above pre-Trump expectations.

These two approaches give the same number — 0.8 percentage points — which is also the increase in customs duties as a share of GDP. Honestly, the results are almost too neat.

Lots of wiggle room at the edges, but the basic point is that there isn’t a big puzzle about the limited effect of tariffs on inflation. Some economists may have overhyped that effect, and Trumpists are happy to promote a straw man, but the reality is that the inflationary effect of tariffs has been more or less in line with what we should have expected.