With attention on orbital data centers, the focus turns to economics

One of the biggest questions in the tech sector has been if AI is the future, where does all the infrastructure go?

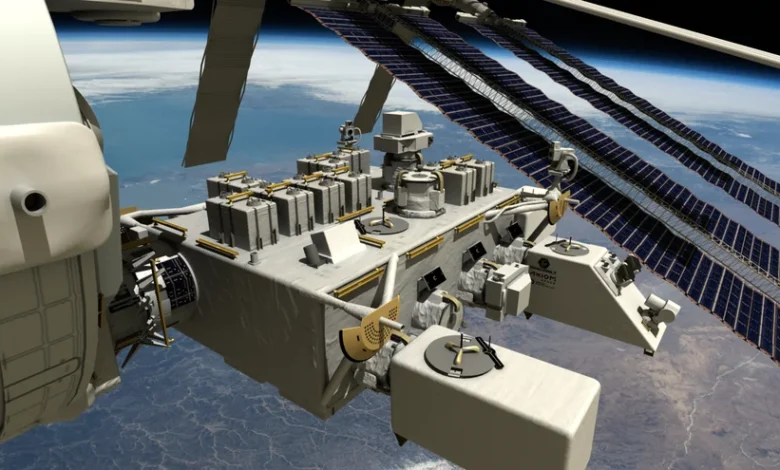

Some space industry leaders — including Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos — believe the answer could be in orbit, via space-based data centers.

That idea has gained attention in recent weeks. Musk is reportedly considering a merger between SpaceX and his generative artificial AI company xAI ahead of his space firm’s planned IPO later this year. In addition, in a filing with the FCC late Jan. 30, SpaceX proposed an orbital data center constellation of up to 1 million satellites in low Earth orbit.

But industry analysts say that while the technological challenges can be surmounted, it’s not yet clear if the business case for data centers in space holds up.

Deep learning models built by frontier labs like OpenAI, Anthropic and xAI all depend on massive clusters of advanced processors operating in data centers. As more deep learning models are built and deployed, more processing power is required — last year companies invested $61 billion in building more data centers. That’s a new record, according to S&P Global, with real estate trackers expecting capacity to double by 2030.

However, there are obstacles facing new data centers on Earth, including environmental permitting, access to electricity for power and water for cooling and community opposition. Microsoft, for example, expects its data center water usage to triple by 2030, according to the New York Times. Data center projects built by Amazon and Chile have been canceled over resource concerns like those.

“The biggest problems are cooling, security, power transmission — all those things can be solved if you just move it into space,” Chris Quilty, a space industry analyst, told SpaceNews. “The big question that has to be solved, can you do it economically?”

Jeff Bezos, long an advocate of moving polluting industries off-world as CEO of Blue Origin, kick-started this discussion with remarks at last year’s International Astronautical Congress.

“We’re going to start building these giant gigawatt data centers in space,” Bezos said. “We will be able to beat the cost of terrestrial data centers in space in the next couple of decades.”

Elon Musk and SpaceX are also onboard. Musk told audiences at the World Economic Forum that it will be cheaper to build data centers in space within three years — although that forecast depends on achieving full reusability for Starship, which Musk expects in 2026.

Meanwhile, start-ups like Starcloud are attempting to build companies around this business, while Google is collaborating with Earth observation firm Planet to launch its own data center pilot in 2027. Chinese companies like ADA Space and Beijing Astro-Future are plotting ambitious space compute architectures.

“The rapidity with which the trend has taken hold has shocked me, even for an old hand,” Quilty said. ”It’s very similar to what happened with direct-to-device — everyone and their brother agreed it was a dumb idea right up until the moment that AST raised a round on the concept.”

Still, much uncertainty remains. “Whether putting data centers in space makes sense or not, and what technologies are needed, depends on the business model,” Akhil Rao, a former NASA economist and managing partner at the frontier technology consultancy Rational Futures, told SpaceNews via email. ”I haven’t seen a business model articulated clearly enough to understand how the system architecture serves particular use cases well.”

Andrew McCalip, the head of research and development at Varda Space Industries, built an online calculator that attempts a comparison of terrestrial and orbital data centers using publicly available data. Right now, it doesn’t pencil out, with orbital data centers costing about three times as much per watt of computing power under his base case.

“If you run the numbers honestly, the physics doesn’t immediately kill it, but the economics are savage,” McCalip wrote in his analysis of the calculator. “It only gets within striking distance under aggressive assumptions, and the list of organizations positioned to even try that is basically one.”

That’s one reason why space data centers have taken a central role in SpaceX’s IPO narrative, which is reportedly planned for June 2026. Justifying a $1.5 trillion valuation is difficult based on the company’s current business lines and revenues, Quilty said, but the company has a record of surprising its doubters. When Starlink was proposed, few thought that phased array antennas could be manufactured at the required scale and cost, but now SpaceX is building them by the millions and selling them for a few hundred dollars a piece.

The latest announcement from Blue Origin may point at a middle ground for AI in space: On Jan. 21, the company announced TeraWave, a new satellite constellation that appears designed to provide new, high-bandwidth connections between terrestrial data centers. Compared to running models in orbit, offering connectivity is a proven way for space companies to dip into the AI surge.

And of course, there is the question of an AI bubble. Analysts have noted that justifying the investment in data centers will require significant increases in revenue — say $650 billion in annual consumer spending, per one JP Morgan analysis — for companies like OpenAI that currently lose tens of billions of dollars annually. AI boosters are confident that they will prove out the value of their software, but users, particularly at the enterprise level, are still figuring out how to generate returns using these tools. If they don’t meet expectations, demand for more processing power could prove elusive.