Ryan Reynolds and Rob Mac on five years at Wrexham: ‘We’ve just got started’ – The Athletic

Ryan Reynolds is the first to admit the origins of his friendship with Wrexham co-owner Rob Mac are a little unorthodox.

“Rob and I first met from absolutely nothing,” says the Canadian. “From vapours, really. It’s not how you usually meet someone. But, after I turned 40, I remember thinking, ‘If I see something beautiful or something I love, I will say it, rather than keeping it to myself and moving on with my day’.

“I didn’t know Rob. But I noticed we followed each other on Instagram. I sent him a little note. I think I even told him not to respond. I just wanted to say I’d enjoyed something he did.”

From such inauspicious beginnings came one of the more remarkable sports partnerships.

The two actors have spent the past five years transforming the fortunes of not only a football club but an entire town (now city) by restoring a sense of civic pride many locals in Wrexham feared had gone for good.

The Athletic is speaking exclusively to Reynolds and Mac to mark their anniversary today. We are five years on from the February 9, 2021 takeover that has effectively rewritten the book on how to successfully run a football club. And this despite the fact, as Mac quips in our interview, “We still don’t 100 per cent understand the sport!”

To recap, the pair paid a token £1 to buy an ailing team who were then playing down in the fifth tier of the English football pyramid, alongside a promise to invest a further £2million. Five years — and three successive promotions — later, that same club are one promotion from the Premier League and were recently valued at £350million ($475m).

It’s a remarkable rags-to-riches story that has been captured in the Welcome To Wrexham documentary series, whose own successes include 10 Emmys.

“There’s an expression we were warned about when having our first baby, and it’s, ‘Long days but fast years’,” says It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia star and co-creator Mac. “That’s exactly what it feels like. It feels like we’ve just got started. And yet it’s been half a decade.”

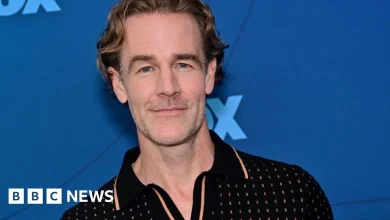

Mac and Reynolds bought Wrexham five years ago (Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

Mac first hit upon the idea of buying a football club after watching the Netflix documentary Sunderland ‘Til I Die. Suitably inspired, he wanted to film the trials and tribulations of sports ownership for his own docuseries, and quickly found a willing partner in the shape of the Disney empire.

Only then did he approach Reynolds. The pair had never met in person, their only previous contact being that private message from the lead in the Deadpool movie series on Instagram.

“What’s interesting is I was talking to Ryan about this recently,” adds Mac. “I said, ‘Do you remember that email I sent you? The original email I sent you?’ I still have that, and read it to him. It was buried deep in Ryan’s archive.

“It really is fascinating, just how much came to fruition and what deviated from the original conception. And how similar and how different it is. Just like life. You make a plan, you do your best, you wake up every day, go to work and see what happens. Sometimes, because of the confluence of hard work, great fortune, amazing partnership and a little touch of the magic and/or football gods, something turns magical.”

Later, after our interview has finished, Mac forwards The Athletic the original email pitch he made to Reynolds, plus the story synopsis that persuaded Disney to come on board. There’s insight offered into not only the thought process behind a project that would subsequently strike sporting gold but also Mac’s incredible vision.

There’s no mention of ‘Wrexham’, or even ‘Wales’, at this early stage. The search for a suitable club, which eventually took in Ireland and Scotland as well as the lower echelons of the game in England, was still in its infancy. But the focus on community that runs through Welcome To Wrexham is very much front and central.

“This isn’t about restoring a football club,” read the missive to Disney. “It’s about restoring a town. A town that was in bad shape before the pandemic. Absolutely devastated now.”

His lengthy email to Reynolds is along similar lines. It’s also dripping with good humour, including the self-deprecating final line, “Anyway… that’s probably the longest email I’ve ever sent. Any interest? Wanna get on the phone and talk about it? Or did you stop reading an hour ago?”

The pitch worked. In time, Wrexham would be chosen as the vehicle and the two actors were gradually drawn into a community that welcomed them with open arms.

“I know I’m a football fan and a Wrexham lifer because I’m inconsolable when we lose,” says Reynolds. “I’ve never been as invested in winning and losing before. I have to fly across the Atlantic when still awake and sober (after a match) and try to process that whole loss. That’s a flight, seven hours long, and for some reason it takes 29 hours.

“My kids get frustrated about it. If we are walking down the street, I’ll get asked about Deadpool (by someone) and it’s usually (just) a two or three-second conversation, basically saying, ‘Hi’. If someone talks about Wrexham, I just turn right round and park it against a street pole. My kids are like, ‘Oh no!’”

Built largely on coal and steel, Wrexham was once an industrial powerhouse.

Its coalfield alone boasted 38 collieries and employed 18,000 people, while another 3,000 worked at the nearby Brymbo Steelworks. However, as those two industries declined and then disappeared altogether from the area in the 1980s, hard times hit.

The town’s football club, whose relatively modest high-water mark of once finishing 15th in the old Second Division belies a history of famous European nights, tackling giants such as Porto and Roma, was not immune to this economic hardship. It famously needed supporters to take charge to prevent it from going under in 2011.

A prime candidate, therefore, for two celebrities from the other side of the Atlantic wanting to film a docuseries about their attempts to revive both a community and its football club.

“From the very beginning, it was, and always will be, about working-class people,” says Mac, who was born and raised in Philadelphia. “The community of Wrexham. That is what always drew me in.

“I just kept looking at the faces of the people, and they looked like me. Like people I grew up with. They looked like my uncles and my aunts and my cousins. My friends, all the people I knew.”

Reynolds felt the same.

“No one survives in the entertainment business for as long as Rob has — or, certainly as long as I have — if you’re a dick to people,” he adds. “We’re aligned because we both came from working-class families who didn’t have much. I had three older brothers, my dad was a cop (in Vancouver), and, as you saw in the first season of Welcome To Wrexham, you really saw where Rob came from. That can sometimes give you a drive, but it can also align your values to a certain extent.

“We both have values that didn’t even need to be identical. Just, at its root, it needed to at least have some sort of understanding that you occasionally get what you need but never what you want, growing up. That seemed to be the norm in Wrexham when we got there for almost everyone. I think everyone felt looked-over in that post-Thatcherism, post-industry (time). I wouldn’t ever call it a dystopia, because there’s always a fire in the belly there. But there was definitely sadness, too.

“Identity is the biggest thing. When you lose your identity, or you feel like you don’t have an identity, it feels like a death in a way. I think the club is symbolic of that.

“There’s a Wrexham in every state in America. And in every province in Canada. Certainly all over the European Union. There are Wrexhams everywhere.”

This belief is why Reynolds finds it hard to understand the negativity in some quarters surrounding Wrexham’s revival in fortunes.

Reynolds and Mac both spoke about the importance of helping the city (Joe Prior/Getty Images)

“You can hate me, you can hate Rob,” he adds. “But you can’t hate that town. I don’t know how you would do that. How can you hate the town of Wrexham? It’s the most beautiful town on earth.”

As with every town and city in the UK, Wrexham still has its share of problems. But there’s also a restored sense of hope. That goes along with the new bars and restaurants opened to cater for the tourists who continue to flock to this corner of north-east Wales, five years on from the first sprinkling of Hollywood stardust.

Reynolds says: “I see the club as the big, beating heart of the community. Basically, Wrexham’s community centre. Or church. One of them, anyway. There’s a real church, of course! They perform the same function, in as much as they bring people together.

“People who have completely disparate ideologies walk through those (stadium) gates, and they are together, wearing the same colour shirt and singing the same, filthy chants. And they are having a wonderful moment together, regardless of what circumstances in life suggest they should be pushed apart. That’s so powerful.”

Saturday brought a rare setback for The Racecourse Ground’s congregation. A 2-0 home defeat against Millwall meant the opportunity to leapfrog the visitors into fifth place in the Championship table was missed. It also allowed the pack chasing Wrexham, who sit in the fourth and final play-offs berth, to narrow the gap, meaning just three points now separate Phil Parkinson’s side from Queens Park Rangers in 12th.

Still, their lofty current league position — nine places above that highest-ever finish of 15th, achieved in the 1978-79 season — is testament to how Reynolds and Mac like to do things differently from most owners. For example, they leave football matters to others, such as Parkinson, chief executive Michael Williamson and director Shaun Harvey.

Next month, the pair plan to break the mould once again by hosting a live broadcast of a Welsh derby fixture at the Racecourse against Swansea City, even joining in with the commentary team during the match. It will fit in with the sense of fun they’ve been determined to enjoy since the very start.

“So many of the questions (we get) are centred around the pressure or the anxiety or the fear,” says Mac. “I think of it as a respite. This is a joy. Every conversation you and I have ever had — and you’ve been around us long enough to know — I love talking about it (Wrexham) and I love experiencing it.

“I’m supposed to be at the ‘Sunny’ set right now, but I get to do this instead.”

The past 16 months have seen two minority investors brought on board by Reynolds and Mac. First, the Allyn family acquired a stake believed to be around 15 per cent, followed in December last year by U.S.-based investment firm Apollo Sports Capital. The second deal, for a little under 10 per cent, valued the club at £350million.

These partnerships are designed to help Wrexham’s off-field operation keep pace with the team’s rapid progress, not least in part-funding the new 7,500 capacity Kop stand currently being built — an element of a stadium masterplan designed to eventually increase capacity to 28,000 which is a key feature of the owners’ much-stated desire to make the club self-sustainable.

“Let’s game this out,” says Mac. “We find a way to pump in enough capital to get Premier League players and wind up in the Premier League. Hell, we even finish top of the Premier League, (but then) the whole thing falls apart because it is an unsustainable model you can’t keep going for generations.

“We’re the villains (if that happens), and we should be, because that is not how you set something up for future success. So, a huge part of the things we talk about now are, yes, infrastructure within the club, but also within the town.”

This planning for the future by two co-owners, very much in it for the long haul, includes opening talks with the city’s Glyndwr University. Its campus shares a border with The Racecourse on two sides. Among other ideas, such as helping the university’s marketing operation, Mac and Reynolds hope to create a programme of “arts and entrepreneurship” to help attract students to the area in their droves.

“(We want to) draw people in, who then stay in Wrexham, to take the artistic spirit and endeavour to build something within the town using arts and business,” explains Mac. “That seems like a sustainable model that could help from a macroeconomic standpoint.

“What we said from day one is we want to build a sustainable model. If anyone looks at the economics of what the club is right now, just by nature of how we got here, it’s not sustainable. But that’s only because the infrastructure hasn’t been there for generations. So, what we are trying to do is plant the seeds so that, yes, we can be successful now, but 50 years or 100 years from now, those seeds become trees and a fully sustainable model.

“Do I want to come and see us win the Premier League? Yes. Do I want to win the Champions League? Yes. But, if Wrexham, as a town, is unsuccessful while we are thriving, we have failed.”

Click here to read part one of our exclusive interview with Rob Mac and Ryan Reynolds