Mass. defense lawyer shortage eases as state ramps up hiring and pay

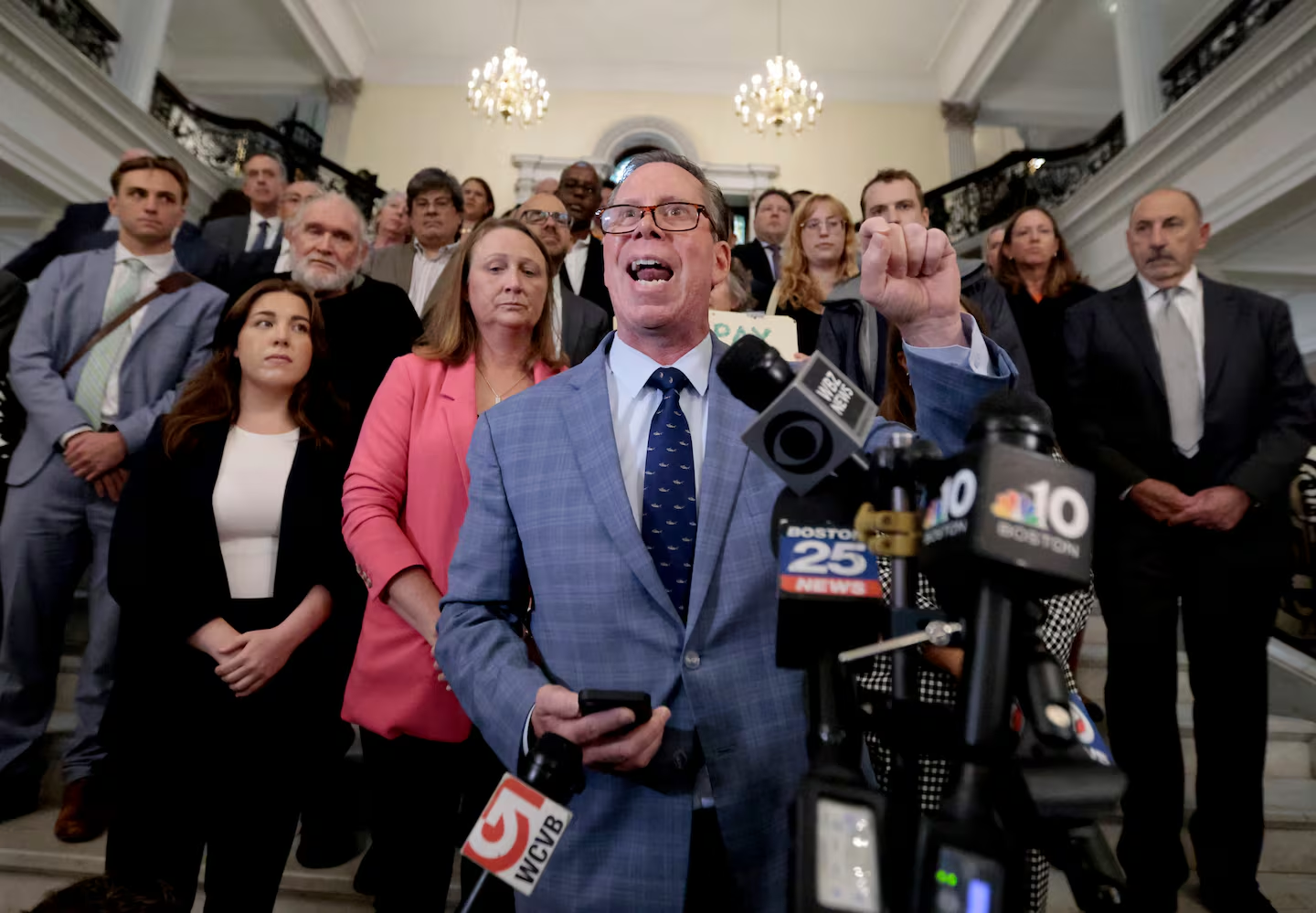

Anthony J. Benedetti, chief counsel for Committee for Public Counsel Services, celebrated what he called a “turning point” in the work stoppage. “We are now able to assign attorneys nearly as quickly as cases are identified,” he said.

The strategy was a quick fix to a work stoppage that reached levels the state had never seen before, but some advocates warn that the crisis is far from over. The monetary incentives the state used to lure some defense attorneys to take more cases run out at the end of March, and it’s not clear what will happen after that temporary fix ends.

“Then we’re just teetering on the edge of being back where we were,” said Shira Diner, a recent president of the Massachusetts Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, who is not a bar advocate but supported their cause.

The incentives are intended to buy time as Committee for Public Counsel Services, the state’s public defender agency, fills hundreds of newly funded public-defender positions to compensate for the dearth of private lawyers who stopped taking assigned cases. At the start of the stoppage last spring, CPCS staff public defenders handled about 20 percent of indigent cases, with the 2,500 or so bar advocates taking the rest; this arrangement was the inverse of many other states, which relied more on staff lawyers to handle cases. A bill signed by Governor Maura Healey in August funds a doubling of CPCS’s staffing in an effort to make the system less reliant on the private attorneys — and less vulnerable to their work stoppages.

In a court filing last month, a CPCS attorney wrote that the ongoing hiring “is unlikely to solve the problem in the short term,” though the agency “expects it to be resolved” once all of the hiring is complete and the new attorneys have the training and experience to handle full caseloads. The filing gave no timeline for when that would happen.

According to a statement from CPCS, it has hired 57 attorneys in the past four months, and another 45 are signed to start in further rounds of hiring in April and September. CPCS expects to hire an additional 50 to 60 lawyers this year as it looks to use the additional funding to add 320 new staffers over two years, effectively doubling the number of public defenders.

This, Benedetti said, “strikes a perfect balance between a robust internal staff and a resilient private bar” that will improve the defense system writ large.

The work stoppage began in late May, as a group of bar advocates who work in Middlesex and Suffolk counties, the state’s two busiest, stopped taking new court-appointed cases to protest their pay rates. At the time, the pay rate for district court work was $65 per hour, far less than what nearby states pay. The bar advocates sought a $60-an-hour raise over two years. The lower rate here, most sides agreed, had led to the number of bar advocates available for work gradually dwindling in recent years even before the stoppage.

Almost immediately, defendants who were declared indigent faced arraignment with no attorney available to take their case. That’s a violation of the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees access to representation. Some defendants, mostly those charged with serious crimes involving weapons or violence, were ordered held without bail after hearings in which they had no one to argue on their behalf.

In early July, a justice of the Supreme Judicial Court ordered the implementation of what’s called the Lavallee protocol, named for a case from 2004, the other time such a stoppage happened. The protocol, meant to protect the Constitutional rights of the accused, sets time thresholds: Anyone held more than seven days without a lawyer must be released, and any case that lingers longer than 45 days without the defendant having an attorney must be dismissed.

Cases dismissed are done so without prejudice, meaning they can be refiled at a later date. In the time since, Suffolk District Attorney Kevin Hayden’s office said it’s reopened more than 100 cases. Prosecutors are prioritizing more serious offenses, such as allegations of violence or repeat offenses.

Within a few weeks of the Lavallee protocol going into effect, regular hearings for releases and dismissals were happening in both counties.

Through Lavallee hearings, judges have dismissed at least 1,687 cases and released 198 people who were held, according to data from the courts. The courts called those numbers conservative estimates.

The dismissals and releases were sometimes over objections of prosecutors, who said some of the people were accused of serious crimes, including weapons infractions and domestic violence.

In early August, the state enacted a law that gave the bar advocates an immediate $10-an-hour raise and another $10 raise effective Aug. 1, 2026. It also funded the large expansion of CPCS.

Some bar advocates trickled back to work, but many held out, and the courts continued to struggle to find lawyers willing to take new cases.

In October, CPCS rolled out the incentive program, through which lawyers could make up to $7,500 by taking cases on top of the hiked pay rate. This proved to be enough to lead some lawyers to begin taking new cases. It was originally slated to end in November, but has been extended three times. CPCS says it has assigned lawyers to more than 1,500 defendants through the incentive program.

In November, the full panel of the Supreme Judicial Court heard arguments about whether the judges should be able to order pay hikes themselves to stem the Constitutional crisis, an authority that is historically reserved for the Legislature.

The SJC has yet to rule, though justices appeared skeptical of involving the courts in budgeting matters.

The argument, for now, is largely academic. The courts have not had reason to hold any Lavallee hearings for at least a month. A lawyer representing the Trial Courts wrote in a recent filing with the high court that only 25 people were recently charged but didn’t have lawyers, including one in custody. None of the cases were in violation of Lavallee thresholds at the time.

Governor Maura Healey’s office pointed to the state’s commitment to funding the trial courts as a way to address the work stoppage, including a proposed 15.9 percent increase for CPCS funding in the next fiscal year.

But Sean Delaney, an original leader in the work stoppage movement, and now the president of the recently created Massachusetts Association of Private Appointed Counsel (a professional organization of bar advocates), said the state must still do more to compensate the private attorneys who take cases and ensure that such a crisis doesn’t occur again.

“This has been neglected for so long,” Delaney said. “The crisis hasn’t gone away. We are not going away.”

Sean Cotter can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him @cotterreporter.