Kevin O’Leary Wants to Be an Immortal Villain

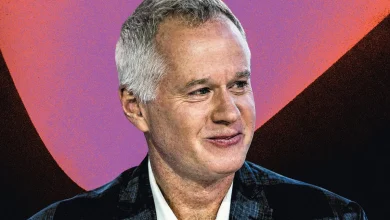

Kevin O’Leary on the set of Marty Supreme.

Photo: MEGA/GC Images

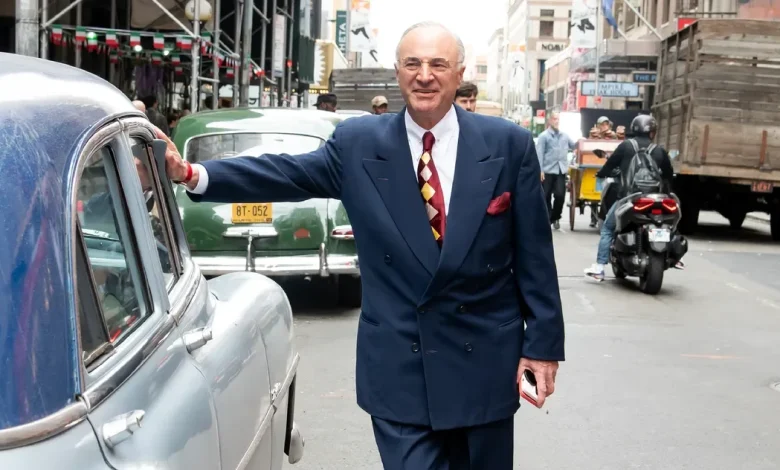

Kevin O’Leary is the reason for the vampire speech in Marty Supreme. He’s showing me evidence on his phone over the table we’re sharing at an Upper East Side brasserie that’s packed with ladies-who-lunch regulars. Marty Supreme is the story of Marty Mauser (Timothée Chalamet), a would-be table-tennis champion whose dreams of greatness are hampered by the fact that no one in 1952 New York City gives a damn about table tennis. O’Leary, who plays a pen mogul named Milton Rockwell, believed so strongly that Marty needed to face greater consequences for what he does in the film that he kept sending director Josh Safdie in-character videos in which he aimed increasingly baroque threats at the protagonist.

The scene instantly cements itself as one of the movie’s high points, an incredible non sequitur that I did not take literally, given that Milton — a real shithead of a plutocrat and the closest thing Marty Supreme has to a main antagonist — has no apparent issues with daylight, food, or sustaining a long marriage to his trophy wife, a former movie star played by Gwyneth Paltrow. But O’Leary very much did. “I wanted to bite him, have blood spurting everywhere,” he informs me. “In fact, we went to the extent that we got a digitization of the vampire teeth to make the prosthetics.” Safdie nixed the supernatural turn, for what everyone aside from O’Leary would likely consider the better. But it remains a perfectly eccentric moment, the kind you can only get by packing a movie with performers who are true characters themselves.

O’Leary, who is better known as Mr. Wonderful to the Shark Tank viewers out there, arrives at lunch in a glossy black-on-black paisley suit jacket, looking a bit lord of darkness himself, despite his tan. (Like any self-mythologizing, right-leaning businessperson worth their salt these days, he’s based in Miami.) Born in Montreal, O’Leary initially made his fortune by founding and selling an educational software company that put out bulk titles on CD-ROMs, then established himself as a personality on reality TV, first on the Canadian competition show Dragons’ Den and then on its American equivalent, Shark Tank, which he has been a part of since its inaugural season in 2009. Over the years, he’s earned a reputation as the meanest of the titular sharks, its Simon Cowell, the angel investor who doles out harsh truths, ridiculous epithets, and elaborate metaphors to wannabe entrepreneurs.

Like the Joker, O’Leary tends to give competing origin stories for his nickname. The version he tells me involves a sarcastic quip made about him by Amanda Lang, with whom he used to host a nightly business-news show on Canada’s public broadcaster, the CBC, called The Lang and O’Leary Exchange. Other accounts allege fellow Shark Tank investor Barbara Corcoran gave him the title in response to the zealous royalty deals he proposed to contestants in season one. However it came about, it’s fair to say that “Mr. Wonderful” is ironic. Fans have made compilations of him calling contestants greedy pigs and telling them he’d like to hire them just so he can fire them. With his dark suit and chrome dome, he’s made himself into a comical avatar of ruthless capitalism, sneering at sentimentality and demanding to know “how do I make money off of depressed people?” O’Leary considers his unfiltered criticisms on Shark Tank to be a service, a way of providing a necessary wake-up call when someone does not have a workable idea and is instead “a loser pissing away their parents’ mortgage money.”

In other words, O’Leary could be regarded as a professional asshole, which is what got him the part in Marty Supreme. “I got a call from Josh, and he said, we’re looking for a real asshole and you’re it,” he explains without a trace of self-deprecation. “It’s not an insult to me — 20 years ago, Mark Burnett said exactly the same thing when he was casting Shark Tank.” It was going to be his first acting role, and his agent at UTA wasn’t enthused about what the venture might do for his client’s brand. “‘We think you could shit the bed’ were the words he used,” says O’Leary. Instead, he is startlingly great in the film, which rises up to cradle his presence like it’s an inlaid gem. Milton — sporting a toupee, an air of smarm, and a sneer that tugs at his upper lip in a way that looks involuntary — is an off-putting counterpoint to Marty’s win-at-all-costs version of American exceptionalism — a man for whom everything is transactional, including the death of his son in the war, for which he expects a thank-you from an Auschwitz survivor he meets.

O’Leary isn’t the only nonprofessional in Marty Supreme’s sprawling cast, which includes rapper Tyler the Creator, real-life table-tennis champion Koto Kawaguchi, filmmaker Abel Ferrara, and supermarket magnate John Catsimatidis. But he’s the one who has to go toe-to-toe with a career-best Chalamet in a series of escalating showdowns in which their characters compete for dominance. One encounter takes place in a restaurant in Paris not dissimilar to the one we’re eating lunch at in New York, during which Milton offers to pay Marty to participate in a promotional event in Tokyo, a prospect Marty finds so offensive (he’d be expected to throw the match to keep Japanese audiences happy) that he retaliates with a crude comment about Milton’s son. O’Leary’s Milton goes still while remaining visibly incandescent with rage. It’s one of the reasons that, after the screening, a documentary producer who is apparently not a reality-TV fan asked me, wonderingly, “Who is that actor? What else has he done?”

That O’Leary could waltz into his acting debut in the movie event of the season is a testament to the certainty he exudes across the table from me like light from a SAD lamp. He’s honed his tough-talking image over years on television, including tireless appearances as a talking head on news shows and a brief flirtation with political candidacy in Canada. In person, he gives a less confrontational version of the bombastic bluntness he affects onscreen. Mr. Wonderful isn’t a persona, he explains, so much as the result of realizing that whether people love to loathe him or loathe that they love him, it’s all better than indifference. “Here’s what I figured out,” he explains evenly as he delves into a salad. “I only need to keep 25 people in my life happy: my immediate business associates and my family. I can’t make 11 million people happy. I have a lot of respect for people — and I get this every day — that write a full essay about how much they hate me. Imagine the amount of energy to compose that.”

@kevinolearytv

It’s a new name for an old idea. Shakespeare wrote outrageous things to sell plays, and ever since then, when the printing press was invented, people wrote outrageous things to sell books, and they always will. The internet’s just another distribution vehicle. The idea of controlling speech online has been elusive. In even China, it’s really difficult. The only option you have is to actually shut it down. Once it’s out there and once people have a VPN or ability to go around the IP that’s been shut down, they get access to it.

♬ original sound – Mr. Wonderful

O’Leary is a well-known wine guy, which is why we end up ordering a bottle of Puligny-Montrachet to share over orders of French onion soup and beef bourguignon. He’s a well-known watch guy, too, who has chosen to accessorize his monochromatic outfit with a vintage pair of red-leather bands — wearing two watches at a time is one of his signature moves — and talks me through their provenance with the practiced ease of someone who’s been delivering this explanation a lot lately. He didn’t want to wear rented watches in Marty Supreme, so he went through the trouble of personally obtaining a rare set that would make sense for the postwar-period setting — one a Patek Philippe; the other, which has a Japanese flag imprinted on it, gifted to him by Seiko with the understanding that it would appear onscreen.

What makes O’Leary feel a little more palatable than some of his fellow moguls turned celebrities of the kayfabe economy is that, despite his love of punditry, he’s not really a culture warrior. During his run for leadership of Canada’s Conservative Party in 2017, he skewed fiscally conservative and socially liberal, proclaiming his opposition to carbon taxes and regulation and his support for LGBTQ+ and abortion rights. (How serious his commitment to becoming a politician was remains unclear, but he appears to have dropped out rather than learn the French necessary to win support in Quebec.) He’s broadly anti-union and harps on urban crime, then he advocates for bank failure. He has supported Donald Trump in the past, though lately he’s been more critical of the American president, especially when it comes to tariffs, certain immigration policies, and the government’s investment in Intel. On the Marty Supreme campaign trail, he offered cryptic assessments of J.D. Vance: “I think anybody that is as close to the sun as he is has done a masterful job at staying out of trouble.”

The actual business advice O’Leary doles out on his social-media channels tends to run toward old-fashioned urgings — to not commit to mortgage payments that are more than 30 percent of your income, to save another 30 percent and invest it — suggestions that no one would quibble with in spirit, even if they have become difficult to impossible to follow in practice. Outside of X and Meta, he stays close to the headlines, if not squarely in them. In 2019, he and his wife were involved in a fatal boating accident; Linda O’Leary was eventually found not guilty of careless operation of a vessel. In 2021, O’Leary became a paid spokesperson and investor in the crypto exchange FTX and lost millions in the company’s collapse. He was part of the People’s Bid for TikTok in early 2025, offering $20 billion in cash to take control of the platform, but no deal closed. He has since come out as a proponent of artificial intelligence, and he believes more movies could be made if filmmakers embraced AI extras.

More than anything, O’Leary is intent on branding himself a champion of capitalism. “I can walk right across the aisle anytime,” he claims. Zohran Mamdani’s team might have rebuffed him when he reached out for a meeting during the recent election, but O’Leary remains impressed by the incoming mayor’s video team and skeptical that he’ll be able to accomplish everything he’s setting out to do. “You’re going to pay terrific taxes,” he informs me with the direness of a gas-station attendant warning a van of teenagers off a spooky cabin by a lake. “You make a media income, but you’re going to get raped.” O’Leary doesn’t care about how that statement comes across. These days, being perceived as a successful businessman is more valuable than being successful at business, and part of that, yes, involves being a prick. Elon Musk, for whom O’Leary’s son worked at Tesla and whom he admires greatly? “A prick.” Steve Jobs, whom he dealt with back in his software-company days? “An absolute motherfucking, cocksucking asshole. The meanest prick in the world,” he informs me with satisfaction.

Despite all that, or, perversely, because of it, it’s fun talking to O’Leary. I actually end up liking him more after he ribs me for the battered condition of the iPhone I’m using to record our conversation and the fact that, despite how I will sail into the Upper East Side chill in a high-end haze of late-afternoon tipsiness, he can easily outdrink me. At the table next to us, a woman who’s been visibly holding herself back through the length of our meal is eventually unable to restrain herself from coming over for a picture and lingering, beaming with pleasure, to talk about Florida and watches and how no one will believe her about this encounter. There’s no expectation that O’Leary’s attitude will be turned on her, but a sense that she would love it if it was. “You’ve got to go see Marty Supreme, Christmas Day,” he advises her instead.

There’s a difference between being a prick and playing one on TV, and O’Leary has turned the latter into an art. He knows we love a heel, especially one who speaks with the frankness of someone indifferent to judgment. He’s not speaking truth to power, but it does feel like a sort of intimacy — even if our underlying susceptibility to that effect has played a large part in landing us where we are today as a nation. O’Leary is aware that he’s unlikely to find another role as good as the one he plays in the Safdie film, but that hasn’t stopped him from thinking about his next big screen turn anyway. “I want to do a movie where I’m a bad guy that uses AI to kill off the planet. The first scene has to be me blowing something up, and after that it gets worse,” O’Leary tells me over glasses of port, practically rubbing his hands together at the prospect. Or maybe, he muses, a Bond film in which he plays the villain as a guy who corners the longevity market and actually comes up with rejuvenation technology that works. “They can’t beat me because I’m perpetual, I found the fountain of youth, and fuck you — you can’t have it at any price.”

That reminds him that last month in Dubai, he tried out extracorporeal blood oxygenation and ozonation, or EBOO, the latest in high-end health trends, in which they drain your blood, run it through a dialysis machine to filter out toxins, then pump it back into you infused with oxygen and exosomes. “Fourteen days later, you feel like you’re 6 years old,” he says. So maybe Kevin O’Leary will get his vampire ending after all — in real life if not onscreen. Though it’s onscreen where he feels like he could really be of service: “I think I could take evil to a new level. It would give a reason for good to exist. I think I could be so bad you would like me.”

See All