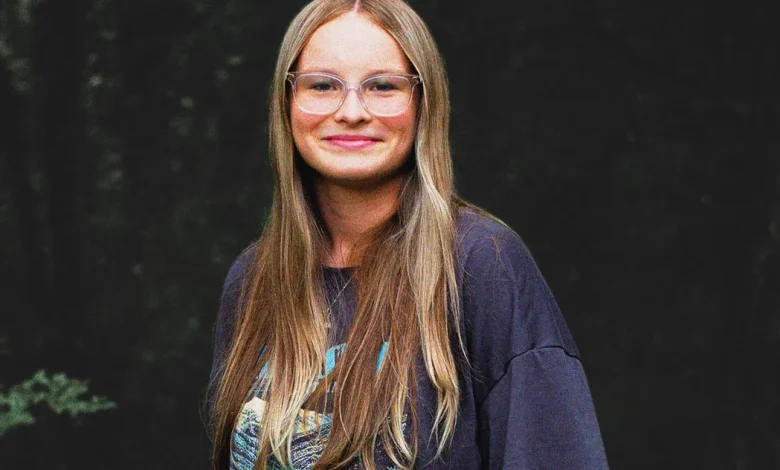

The 15-Year-Old Challenging Transgender Sports Bans

Photo: Scout Tufankjian/ACLU

On Tuesday, 15-year-old Becky Pepper-Jackson sat before the highest court in the United States while the justices debated whether she should be allowed to participate on her West Virginia high-school girls’ track-and-field team. It was the climax of a nearly five-year-long legal battle that Pepper-Jackson has been fighting since her home state passed HB 3293, which banned trans girls and women from participating on sports teams that align with their gender identity. In practice, that law has affected exactly one known athlete: Pepper-Jackson.

For the most part, she’s still been able to throw shot put and discus — she placed third in the state last year — as her case has worked its way through the courts. But this spring may mark Pepper-Jackson’s last season in high-school sports. During oral arguments in her case and the case of another trans student athlete in Idaho, the court’s conservative majority seemed skeptical of arguments that bans on trans athletes violate their rights and open to concerns that trans girls and women have an unfair advantage in sports. Part of the ACLU’s argument in the case hinged on Pepper-Jackson not having an advantage over other girls because she had undergone hormone therapy before hitting puberty. The justices will likely make their decision in June.

I caught up with Pepper-Jackson after she left court for the day about what it feels like to be at the center of such an intensely political case, the surreality of watching the Supreme Court argue about her ability to do the sport she loves, and what comes next for her.

I first realized my participation in athletics as a trans girl was a question when I was going into sixth grade, at 11 years old. I was getting ready to sign up for my first season of track when my mom told me a West Virginia bill could mean I wouldn’t be allowed to play. I’m from a family of runners, but in junior high, my track coach encouraged me to try shot put and discus. She brought me over to the practice area and everybody was just super-friendly. It felt like a really nice community.

It’s very hard to learn that some people think it’s wrong for you to do the things you love. When the legislation passed, I instantly wanted to know what I could do. I wanted to keep playing, so it was a relief when we decided to take legal action. Now, I’ve been a part of this case for five years, and there have been some definite lows and highs. Ahead of my seventh-grade season, the initial injunction that let me play was dissolved by a district court. At that time, track was starting in two weeks. I was worried. I couldn’t miss tryouts, or I wouldn’t be on the team. Luckily, an emergency appeal was granted. When I found out, my mom and I hugged, and I gave my three dogs some love. We celebrated with mint chocolate-chip ice cream and rainbow sprinkles. I was ecstatic because I knew I could play with my friends again.

The 2024 Harrison County Middle School Championship was also a tough moment. Some girls from another school protested my participation in the event by scratching, or refusing to throw the shot put. It felt weird to know that people I’ve never met, who are my age, are protesting me when all I’m trying to do is have fun with my teammates — to be a kid like them. It feels targeted, because it is. My teammates were what helped me that day. They wanted to make sure it didn’t get to my head and affect my throwing or affect me on a deeper level. Everybody is really supportive; we want to see each other succeed. All the throwers stay close. At practice, we share tips. On the bus, we’ll double up in the seats. We’ll try to keep each other’s spirits up and beat the nerves. We talk and talk to take our minds off of the competition.

Protesters or not, I’m always super-nervous when I get up to throw. So much is going through my head: How can I make my throw the best it can be? But after I get in the ring, I tend to calm down. A lot of people spin around as they prepare to throw the big ball we call the “shot.” But, personally, I glide. I’m essentially donkey-kicking backward to the front of the ring and letting go. That’s one thing sport has taught me: There’s more than one way to find success. It’s also helped me learn when to overthink and when to just breathe. Overthinking is what makes me good at discus. But at shot put, I have to shut everything out and just let my body do it. If I overthink, then I mess up.

As the Supreme Court looks at my case, I’m just remembering that I need to calm down, take a deep breath, and be myself. Hopefully, I’ll glide through this, too.

It felt weird to hear the justices talk about me. It felt like I wasn’t there.

This morning, as we walked up the steps of the building, it didn’t hit me for a second that this was the highest court. I know photos aren’t allowed, and not a lot of people have seen what it looks like inside the building. I tried to take in every moment and know that this could be the only time I’ll ever see it. I loved the architecture and the engravings around the ceiling area. They showed Greek gods, Aristotle, and Socrates. We passed by paintings of past justices like Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

I took a blank legal pad with me into court so I could write things down that I thought were funny and interesting. I didn’t know the justices’ names by how they looked, so I had my lawyer make me a seating chart. They heard another case before mine. Some of the justices had really good questions, others didn’t seem too interested in anything. It’s long and it gets a little boring, so you’re getting comfortable — a little too comfortable, and kind of drifting off. My older brother actually fell asleep at one point, so I wrote down his name and then sketched a little drawing of him with a bubble coming from his mouth with Z’s in it, like in a cartoon.

When my case was being argued, it felt weird to hear the justices talk about me and say my name right in front of me. It felt like I wasn’t there. You’re hearing facts about yourself; they’re talking about hormone blockers and going through female puberty. I know it’s the truth, so it’s not like they’re saying anything bad about me. It’s just a little weird to hear people talk about you and not to you.

People, including Justice Kavanaugh, have made the argument that my participation in sports means it’s not fair for other people — like I’m taking a spot or someone else’s medal. I know from losing myself that it does hurt to get beat. Typically, you want to find something to blame. People blame me a lot of the time. I put in so much work and effort, but I know what it feels like to get beat because I’m not winning all these meets. I learned from those mistakes and I practice.

I’ve had so many people reach out to me when I’ve been having bad times because of my court case. People I’ve never talked to have messaged me to telling me they’re here for me, that they support me. It’s nice to talk to other trans teens, because they’re going through different experiences. Do these positive messages outweigh the hateful ones I get? Honestly, no. There’s a lot of hate, and I’ve learned that I have to deal with it. I know a lot of the hate comes from people who aren’t educated. I can’t blame them completely because of a lack of education. Whenever people I don’t know despise me, it’s like, why? But there is still enough support in the world that I have hope.

At the end of the month, track season will start, and it could be my last. Going forward, I just want to make the most of the memories I get with my friends. I will have those forever. Sports have taught me a lot, including that it’s okay to lose. If I lose this case, what’s keeping me going is I would still have music, playing the trumpet in my high-school band. If we win this case, I’ll get back to being a kid doing what I love.

I just hope the justices understand that I know who I am. There’s a big misconception that trans youth don’t know who they are yet, that they’re just doing this on impulse, and it’s a big mistake. But I know who I am. Sports are a big thing for me and I’m not trying to get a one-up on anybody. I’m just trying to have fun with my friends.

I’m from a small place in West Virginia, and sometimes it doesn’t hit me how large this case is and what it means to people. As I left the Supreme Court, there was a huge rally as I was walking down the steps. They were chanting “Trans power,” and they were chanting my name and my mom’s name. I was just in this courtroom for four hours, and now, suddenly, there are hundreds of people supporting me. It felt like if you’re in a really cold house, and then suddenly you open the oven, and there’s all this warmth that’s coming at you.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.