Rage in the U.S.A.

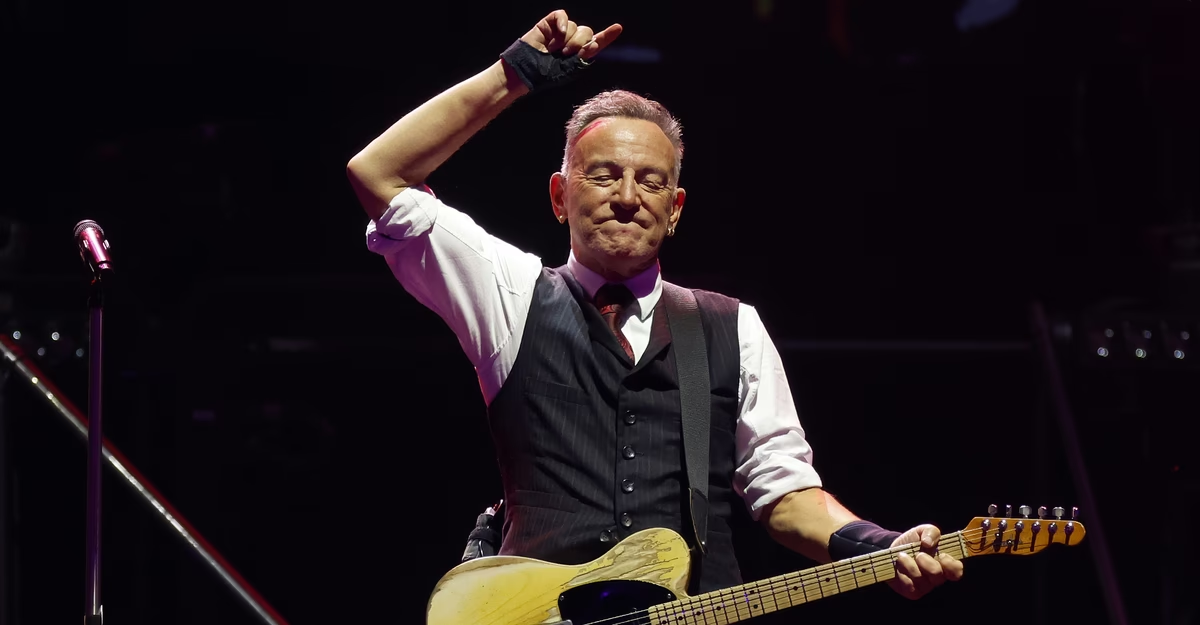

The first few strums of Bruce Springsteen’s new song make you feel like you’re in for, well, a Bruce Springsteen song—a rollicking sing-along about rough-and-tumble but ultimately hopeful times in some troubled American town. And this song, “Streets of Minneapolis,” is exactly that.

It’s also a response to ICE’s bloody record in Minneapolis. It excoriates, by name, Kristi Noem, Stephen Miller, and “Trump’s federal thugs.” It memorializes Alex Pretti and Renee Good—the Americans killed by federal agents—and the “whistles and phones” still in use by demonstrators. The song’s considerable power lies in the way it transposes a classic, even hoary, mode of protest rock into the present. Springsteen conveys that we’re living through a time that will be sung about for years to come, and that the future depends a lot on what we do in this moment.

Springsteen has made many protest songs: the inequality elegy of “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” the post-9/11 rallying cry of “The Rising,” the Vietnam-veteran anthem “Born in the U.S.A.” As a reaction to law-enforcement overreach, “Minneapolis” especially recalls Springsteen’s 2000 song “American Skin (41 Shots),” about the police killing of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed Black man. And across his catalog, Springsteen’s concrete lyricism and drawling vocals channel folk music’s titans of protest, Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie. Here, those influences are worn proudly, ringing out in a buoyant harmonica solo.

But the song that “Minneapolis” most evokes is Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young’s 1970 touchstone, “Ohio,” recorded after the National Guard killed four students during a protest at Kent State University. “Tin soldiers and Nixon coming,” sang Neil Young in a scene-setting verse; “King Trump’s private army from the DHS,” sings Springsteen now. Here we are again, late in a culture war, with a champion of a supposed silent majority breaking norms and pushing polarization. Here we are again as armed agents menace civilians. “Ohio” crystallized a moment that had already captured national attention, but it also invited listeners to suss out where they stand. “What if you knew her and found her dead on the ground?” Young asked. “How can you run when you know?”

“Streets of Minneapolis” doesn’t bother with questions. Its mission is to rouse in the manner of drinking songs, which its sloping melodies and gang-sung harmonies evoke. Springsteen has sounded bitter before, and mournful, but never this purely angry. His voice slithers and spits, reserving extra phlegm for the names of Donald Trump and his allies. Grace and warmth peek out in strategic moments as well, like the chorus’s oh-so-slowly intoned slant rhymes: the words Minneapolis, stranger in our midst, and—the poignance of this one took a moment to understand—26.

Twenty-six as in 2026: the exotic-sounding name of this new year in a decade that remains baffling more than halfway through. Who expected to be living this far in the future and yet trapped in the same old story? One can trace Minneapolis back not only to Kent State but also to the civil-rights movement, and to the labor riots and fascist takeovers abroad that inspired Guthrie. The details change, but the fundamental shape of the struggle remains stubbornly familiar: On one side, gun-toting agents of the establishment; on the other, advocates for the freedom of the less powerful. The clashes result in deaths that get called “senseless” but take on enduring symbolic weight thanks to songs just like this one.

To be clear, “Minneapolis” is not “Ohio,” a paradigm-pushing masterpiece. Springsteen’s language—“thugs,” “King Trump,” “they trample on our rights”—is more Facebook post than poetry. The wordplay about fire and ice and ICE is cheap. The music is heavy-footed and formulaic. The immediate acclaim for it makes the critic in me a little resentful: Artists of all kinds routinely make songs engaging with their times, but so often these days, prestige is reserved for the music that copies the Boomers’ glory days. However, as this song suggests, that era shines in the public memory for a reason.

After sitting with “Streets of Minneapolis,” I tried again to get into Jesse Welles, a 33-year-old folk singer who makes scathingly anti-Trump songs with titles such as “Join ICE” and “No Kings.” Musically, he imitates Dylan and Springsteen to the point of parody. The way the media and rock institutions have embraced him—he’s played Stephen Colbert, performed with Joan Baez, and is up for four Grammys this year—implies that he is the great hope for musical resistance, but his blend of modern buzzwords with Woodstock aesthetics has struck my ear as injuriously hokey.

This Springsteen song has changed my ear a bit. I’m starting to hear Welles and other singers like him—we’re in a bit of a boom for conscientious folk rock—a little more generously. That they’re singing at all, and that anyone is listening, really does matter. Culture, we all know, has become fractured. The easiest way for Trump to get everything he wants is for his opponents to fail to speak in a unified voice. Thinking back to the last time such unity seemed possible isn’t nostalgic—it’s practical.